Men soon grow sick of battle; when Zeus the steward of warfare tilts the scales, and cold steel reaps the fields, the grain is very little but the straw is very much. The belly is a bad mourner, and fasting will not bury the dead. Too many are falling, man after man and day after day; how could one ever have a moments rest from privations? No, we must harden our hearts, and bury the man who dies and shed our tears that day. But those who survive the horrors of war should not forget to eat and drink, and then we shall be better able to wear our armour, which never grows weary, and to fight our enemies for ever and ever.

The Iliad , Book 19

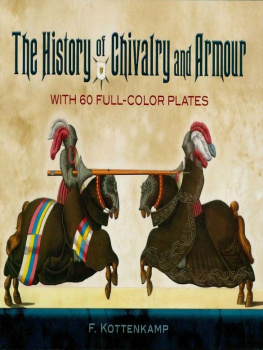

Cover illustration. A cavalryman from the Stuttgart Psalter . (Wrtenburg State Library)

The author would like to to thank Michel Dziewulski of the National Museum in Krakow and Karen Watts of the Royal Armouries Museum for facilitating access to items in their respective collections; Donald LaRocca of the Metropolitan Museum for invaluable references and clarification of unpublished details of items in that collection; Mamuka Tsutsumia for providing information on Eastern European finds; and Nadeem Ahmad for useful discussion.

About the author

Timothy Dawsons interest in medieval history, and especially military history and that of the Near East, was initially fostered by his participation in historical recreation (re-enactment) and public education. Such interests led him to a career as a history educator and historical craftsman. He took a BA in Classical Studies at the University of Melbourne, Australia, followed by a doctorate at the University of New England (New South Wales, Australia). He has published widely on aspects of material culture and social history, particularly clothing and military matters, using a methodology which combines conventional scholarship with practical experience and reconstruction to make significant advances in certain areas. Timothy is the author of Byzantine Cavalryman: Eastern Roman Empire, c.9001204 and Byzantine Infantryman: Eastern Roman Empire, c.9001204 for Osprey Publishing and One Thousand Years of Lamellar Construction in the Roman World , Levantia Guides no. 8.

CONTENTS

The question of whether men first contrived protective equipment for themselves to defend against beasts they set out to hunt, or whether it was the result of conflict arising between human communities, is likely to remain a mystery. What is beyond doubt is that once the need for such protection was perceived, the earliest manufactured form must have been small pieces of naturally occurring durable material, horn and bone, bound together with textiles or leather to create a fabric. This volume sets out to gather the hitherto dispersed evidence for external small plate armours as they were used in the West, to illustrate the permutations in form, and trace the fluctuating patterns of usage.

In defining the West, I use the conventional border of the line of the Ural Mountains, the 60 East meridian. This will, admittedly, take in areas that many people might not think of as Western, such as Iran and Arabia, but the former is certainly fitting, because external small plate armours were central to its military practices for a very long period of time, and because of the significant influence that region exerted on Mediterranean and Near Eastern societies in early times. The reason for the geographic restriction is primarily linguistic. It is very much harder for me to access source material from the Far East. The restriction is not absolute, however. From time to time I will refer to Oriental material for the sake of comparison where that is useful.

In its final realisation, the temporal parameters of this project have ended up being rather wider than anticipated. The starting point in the Bronze Age was noted by earlier scholars, and nothing has arisen in the last few decades to alter that. Rather unexpected, though, was the discovery that scale armour, at least, remained in functional military use much later than I imagined, beyond the middle of the nineteenth century. An epilogue to that is the use of scale armour in theatre and other pastimes, which brings us to the start of the twentieth century.

Origins of the armour

The origins of external small plate armour are lost in prehistory. While scale armour begins in very elementary form and becomes more sophisticated over time, the very earliest surviving examples of lamellar and its representations already appear in sophisticated forms from the outset. That those early sophisticated forms do not survive and spread implies they they did not necessarily have a considerable prior history involving gradual technological development, but perhaps were localised products of some unusually inspired artisan or group. Lamellar is often thought to have been introduced to the West from Central Asia in Late Antiquity, yet in 1967 H. Russell Robinson observed that the earliest evidence for lamellar is actually found in the West. This observation still holds true, despite all the research and archaeology that has been carried out since, with lamellar not reaching the Far East until Late Antiquity. Decades earlier, Bengt Thordeman felt able to be much more definite, writing that the evidence proves that lamellar construction originated in the Near East. With all due respect to Thordeman and many others, we should be wary of one assumption, which is very prevalent in studies of the history of art and technology. That assumption is that any basic technological innovation necessarily arises in one location alone and disperses outwards from there. The creation of segmental armours like lamellar and scale is a technology which could easily have been invented in more than one location independently, with the flows of dispersal from any one locus of invention fluctuating over time.

The genesis of these armours may in fact lie in the late Stone Age. Across Europe and the Caucasus, graves have been found with assemblages of pieces of bone, horn or shell that have been pierced and somehow bound together as bodily adornments, sometimes in quite complex structures. It is notable that in some areas male bodies in particular had such structures encompassing their heads. It is quite plausible to imagine that a man wearing such ornaments might well have found himself in a hunting incident or conflict situation which showed the potential protective value of such a bone or horn fabric and thereby led to the construction of a denser structure designed for that defensive purpose.

Another consideration to bear in mind in terms of technological development is that, just as it may not be singular and geographically contiguous, it also need not be chronologically continuous. A technology may die out and be revived, either anew or from artistic or physical survivals. This phenomenon is conspicuous in the cases of both these armours. For further discussion of this, see the introduction to the section on lamellar.

Sources for the armours

The sources for external small plate armours are fourfold:

Firstly, examples that have been preserved complete or substantially so in collections. These are confined to the modern era. Provided that the material has not been aggressively conserved, or modified to conform to contemporary tastes (as so much armour was in the nineteenth century), the information it provides can be taken at face value, and can shed light upon prior practice.

Secondly, archaeological finds. The condition, and hence information value, of this material can vary enormously. Much has been found as disarticulated fragments, and so these cannot in themselves be very informative. Even better-preserved examples have sometimes been misinterpreted by non-specialists dealing with the finds. A significant amount of the material in major collections was either excavated in what would now be considered an unacceptably unscientific manner, or else was acquired through the commercial antiquities market. The latter has long been prone to having the provenance details of artefacts embellished, or simply falsified, for a variety of reasons. Hence, one must sometimes be very sceptical of the information that accompanies some items.

Next page