loose again and running wild through the "Required Reading List"

Richard Armour

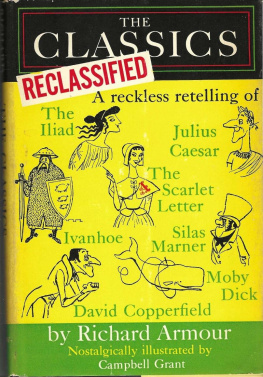

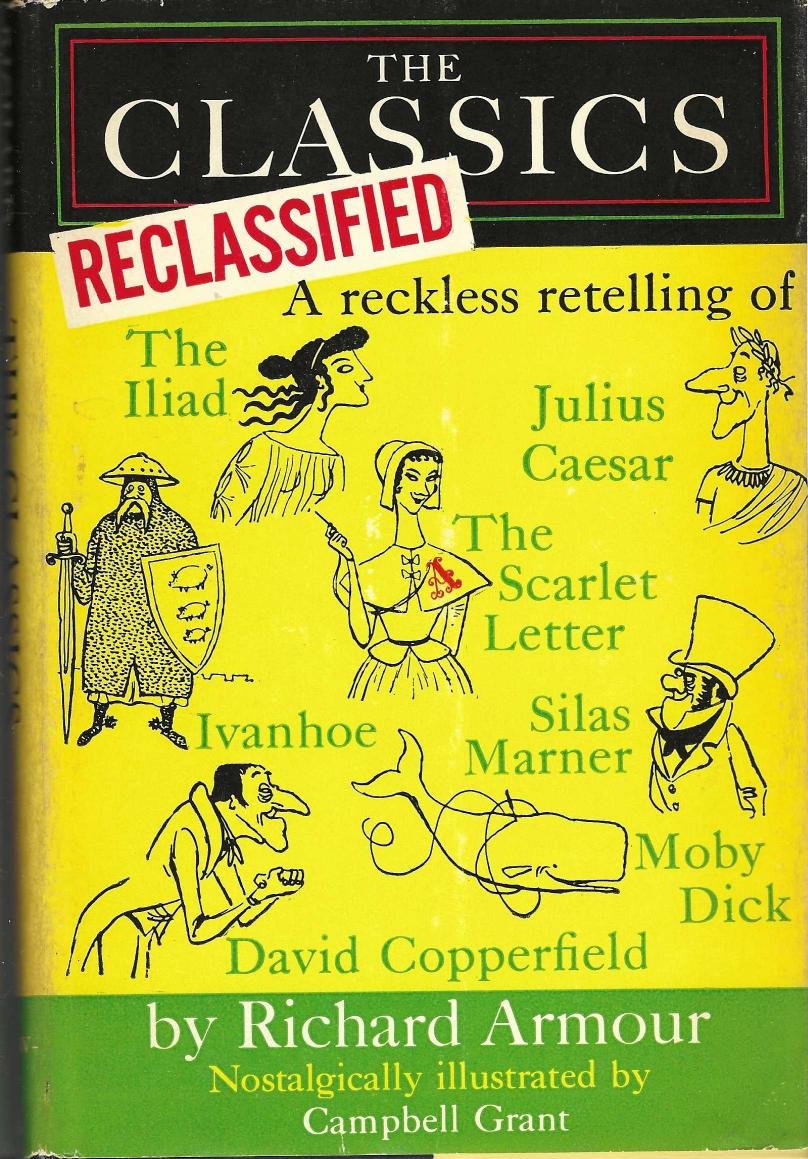

THE

CLASSICS

RECLASSIFIED

To the delight of everyone who has ever drowsed in school (including not afew teachers), Richard Armour has written this fiendish satire on the classics(otherwise known as old chestnuts), which make up that perennial academic swordof Damoclesthe Required Reading List.

The result is incredible.

Describing the infamous list as "better even than artificial respiration forkeeping dead authors alive," Armour retells seven great works, identified(though scarcely recognizable) as The Iliad, Julius Caesar, Ivanhoe, TheScarlet Letter, Moby Dick, Silas Marner, and David Copperfield. He alsoincludes briefmercifully briefbiographies of the authors, nails down hissources(occasionally hitting his thumb), and tests the reader with some highlyuseless questions.

Here is a fresh, if slightly precarious, slant on such learned matters asthe Oral Tradition in Greek poetry, "which finally died out in 329 B.C. duringan epidemic of laryngitis," and the Homeric Cycle, on which the author of TheIliad pedaled around Athens.

Armour is equally astute (and irreverent) throughout his entirereclassification of the classics. In tracing the effects of Shakespeare'sboyhood as a butcher's apprentice, he explains that "all that skewering andhacking was later faithfully reproduced in the fifth act of each of thetragedies."

Scholars the world over (and this means you) are going to find out at lastwhy people visiting Sir Walter Scott's country estate always approachedcarrying umbrellas. That Hawthorne's interest in original sin was "highlyoriginal" indeed. And that George Eliot's head was so big, it looked as thoughit belonged on a horse, and how a cast was made of it, and who held her head inthe platter.

But to go on would be madness. TheClassics Reclassified is a wild but far from woolly parody of scholarship,beyond description and beyond belief. If the reader learns anything, it will behis own fault.

The quizzes and footnotes are duly, but never dully, something or other. Forthose who cannot read between the lines, where Armour is at his best, or whocannot read at all, there are 79 drawings by CampbellGrant, whose work lends much to thegeneral air of meaningful absurdity.

jacket design by CAMPBELL GRANT

THE CLASSICS RECLASSIFIED

Copyright 1960 by Richard Armour.

Printed in the United States of America.

All rights reserved. This book or parts

thereof may not be reproduced in any form

without written permission of the publishers.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 60-14610

First Printing, September, 1960

Second Printing, January, 1961

Third Printing, March, 1962

Fourth Printing, May, 1963

Fifth Printing, March, 1966

Sixth Printing, February, 1967

Seventh Printing, December, 1967

45678910111213 VB VB 7543210698

02256

D edicated

to that amazing device, the Required Reading List, better even thanartificial respiration for keeping dead authors alive.

Contents

HOMER

Almost nothing is known about Homer, which explains why so much has beenwritten about him. We do not know, for instance, whether Homer was his firstname or his last name. After all, Horace was Horace's middle name, so you nevercan tell.

Nevertheless, it seems well established that Homer was born in Greecealucky break for Greek literature. He is said to have been born in seven cities,which indicates how his mother kept on the move. He is also said to have beenborn in six centuries, apparently after a number of false starts.

Herodotus and others have described Homer as blind, although internalevidence in his poems suggests that he had an eye for the ladies. He is thoughtto have been a poverty-stricken poet, unable to make a living at his craft, andthus seems remarkably modern.1 1 It seems silly for scholars to argue about when Homer flourished. Obviouslyhe never did. Whether he evermarried is not known, though one critic seems positive that he remained abachelor. "The author of the Iliad and the Odyssey," this scholar opines, "wasa single person."

The Homeric cycle

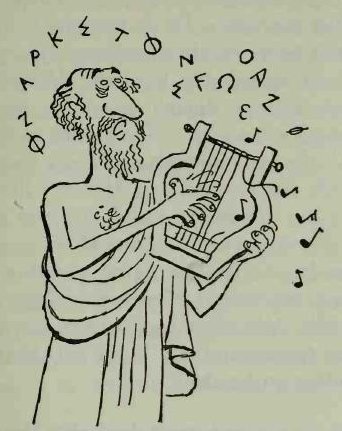

We can only conjecture about Homer's life in Athens. Reference to the"Homeric cycle" suggests that he got about on some sort of wheel, perhaps ofhis own invention.2 2 See Pope's famous remark: "Homer is universally allowedto have had the greatest invention of any writer whatsoever." He must havebeen a familiar figure, pedaling around the Parthenon and coasting recklesslydown the steep roads of the Acropolis. Athenians kept a wary eye out for him,often shouting to one another: "Look out! Here comes the blind poet riding nohands!"

Far from being one of the pillars of Athens, a city that had plenty of them,Homer seems to have been a slovenly type. We are told that Pisistratus, tyrantof Athens between 560 and 527 B.C., was "the first to arrange in their presentorder the books of Homer, which were previously in confusion. " It took atyrant to straighten out the mess he left, his mother and the local librarianhaving given up in despair.

The house in which Homer lived has never been identified. What might havebeen a source of income has thus become a source of regret to Greek travelbureaus and Athenian guides. Indeed the only clue to the environment in whichhe wrote is the fact that he sometimes used the Attic dialect. For centuries,researchers have poked around under the eaves of ancient buildings, looking formanuscripts.

Most scholars believe that Homer wrote nothing down, perhaps not wishing toleave any incriminating evidence. Instead, he recited his poems on streetcorners, in the market place, and on those increasingly rare occasions when hewas invited to someone's house for dinner. It took him about twenty hours torecite the whole of the Iliad, not counting interruptions for applause andthreats of violence. By starting at dawn, he could get through shortly aftermidnight, which left him about four hours' sleep before commencing the Odyssey.When he became famous, the marquee on the Parthenon announced "Homer in theIliad and the Odyssey," the first double feature in the history of thetheater.

This was the beginning of the Oral Tradition, which finally died out, in 329B.C., during an epidemic of laryngitis.

Homer's works are epics, which means that they begin in the middle of thingsand keep the reader confused to the very end. The characters are of heroicmold, probably from standing out in the rain all these years. There are manyepic digressions, for Homer's mind wandered considerably in his lateryears.3 3 Along with Homer, as he went from town to town. Finally, there is epicsweep, adevice used to whisk characters off the earth when the author is through withthem.

The marked difference between the styles of his two great epics has givenrise to the theory that Homer was a man when he wrote the Iliad and a womanwhen he wrote the Odyssey. This is the sort of thing that makes life difficultfor a biographer, but not nearly so perplexing as it must have been for hisfriends.

If Homer was born in the ninth century B.C., he probably died in thatcentury or in the eighth, since people lived backward in those days. GilbertMurray speaks cheerfully of "the condition of Homer in the second centuryB.C.," but one doubts that it was any too good.