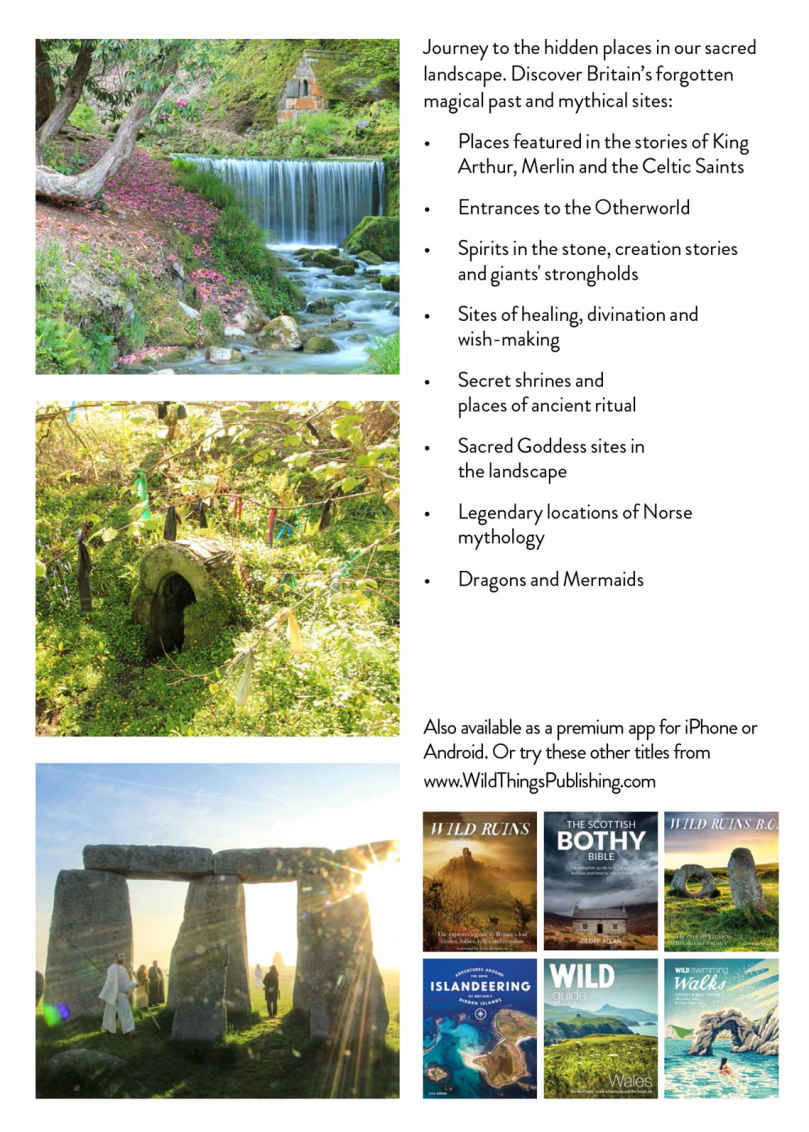

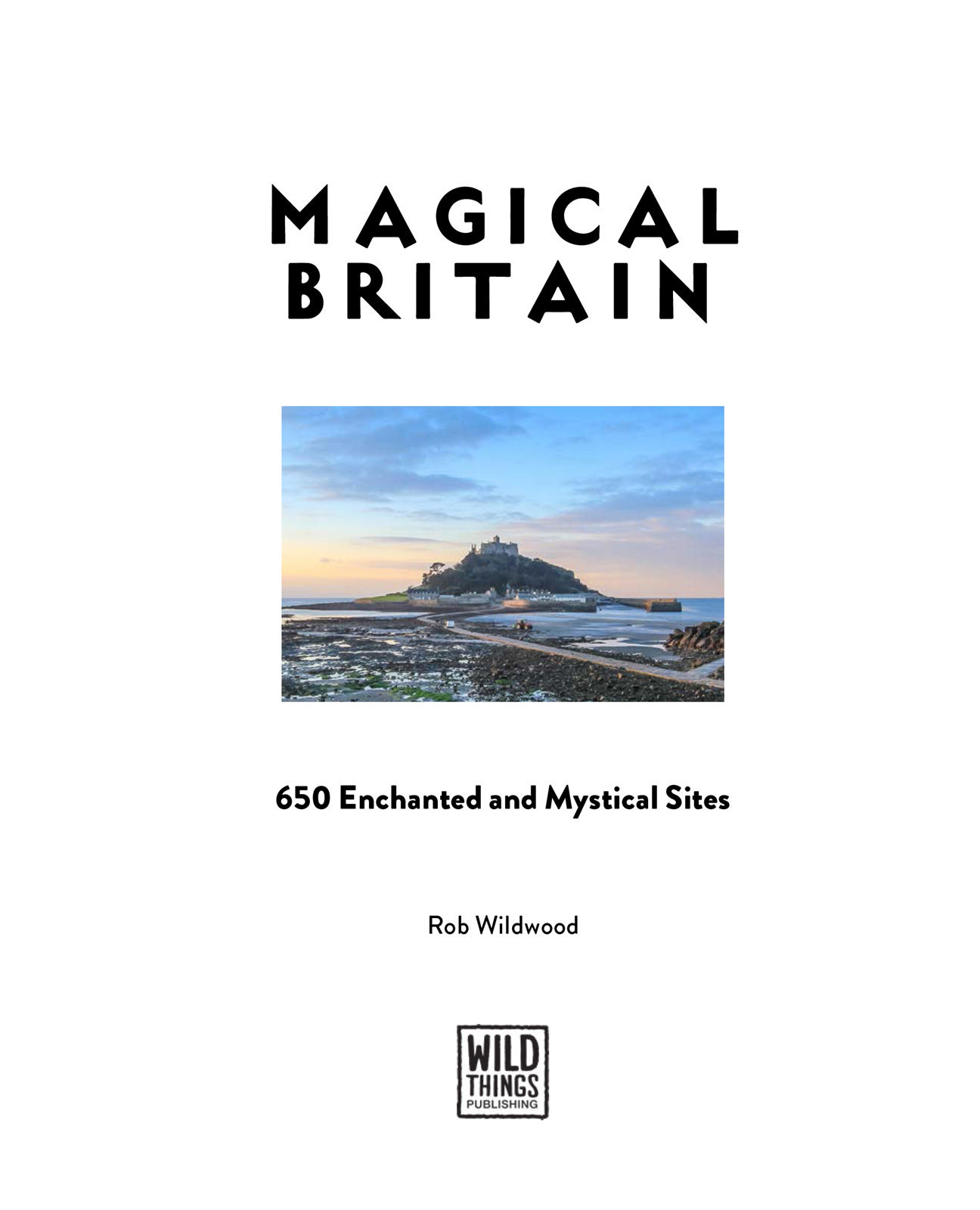

Magical Britain

650 Enchanted and Mystical Sites

Words:

Rob Wildwood

Photos:

Rob Wildwood

Additional research & writing:

Bryony Whistlecraft

Editing:

Anna Kruger

Layout & design:

James Pople

Tina Smith

Illustrations:

Dan Bright (symbols)

Yannick Dubois (Celtic Wheel of the Year)

Proofreading:

Bethany Williams

Distribution:

Central Books Ltd

50, Freshwater Road

Dagenham, RM8 1RX

020 8525 8800

Published by:

Wild Things Publishing Ltd. Freshford, Bath, BA2 7WG

Contact:

Copyrights:

Text and photos copyright (c) Rob Wildwood. First edition published in the United Kingdom in 2022 by Wild Things Publishing Ltd, Bath, United Kingdom. The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

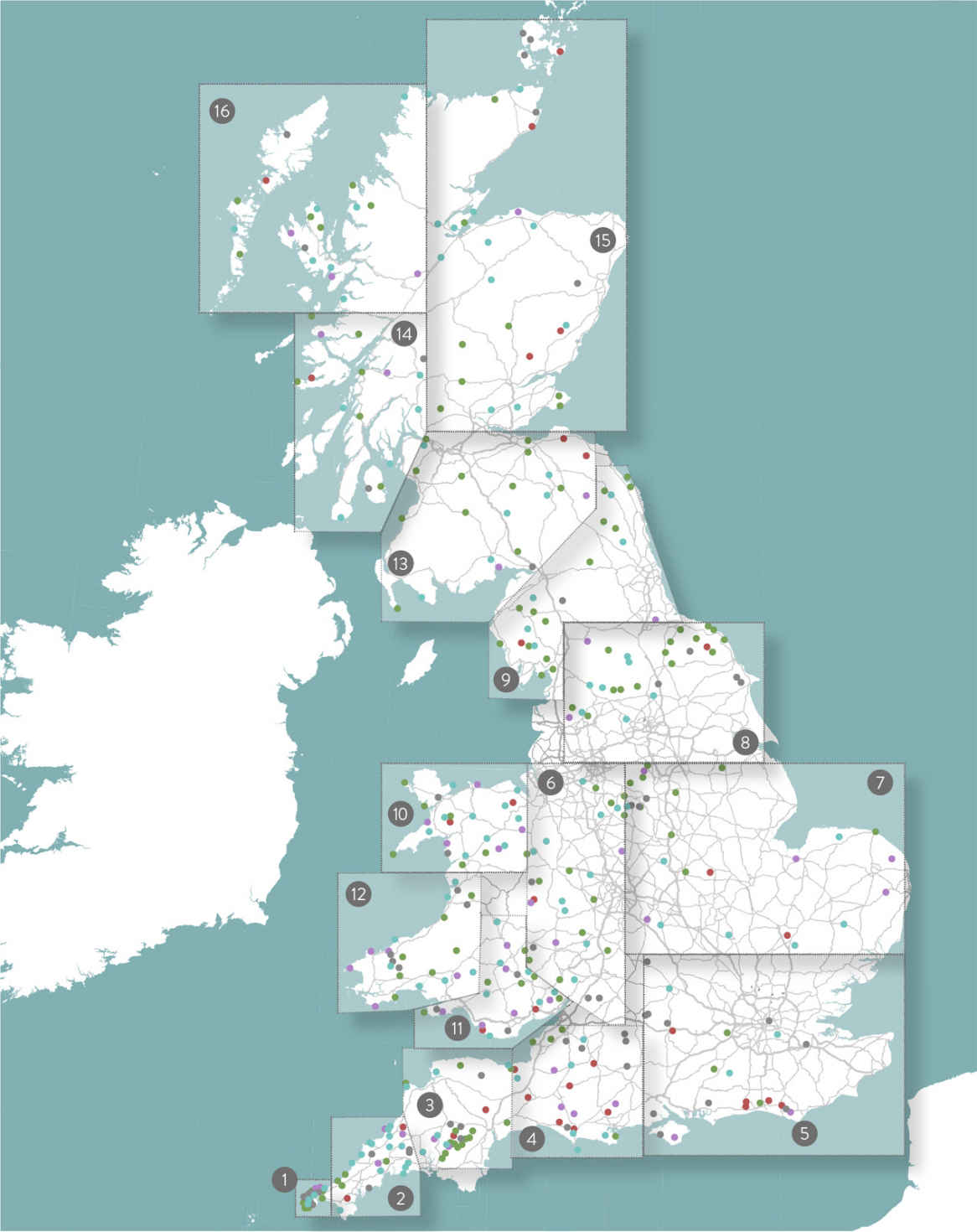

CONTENTS

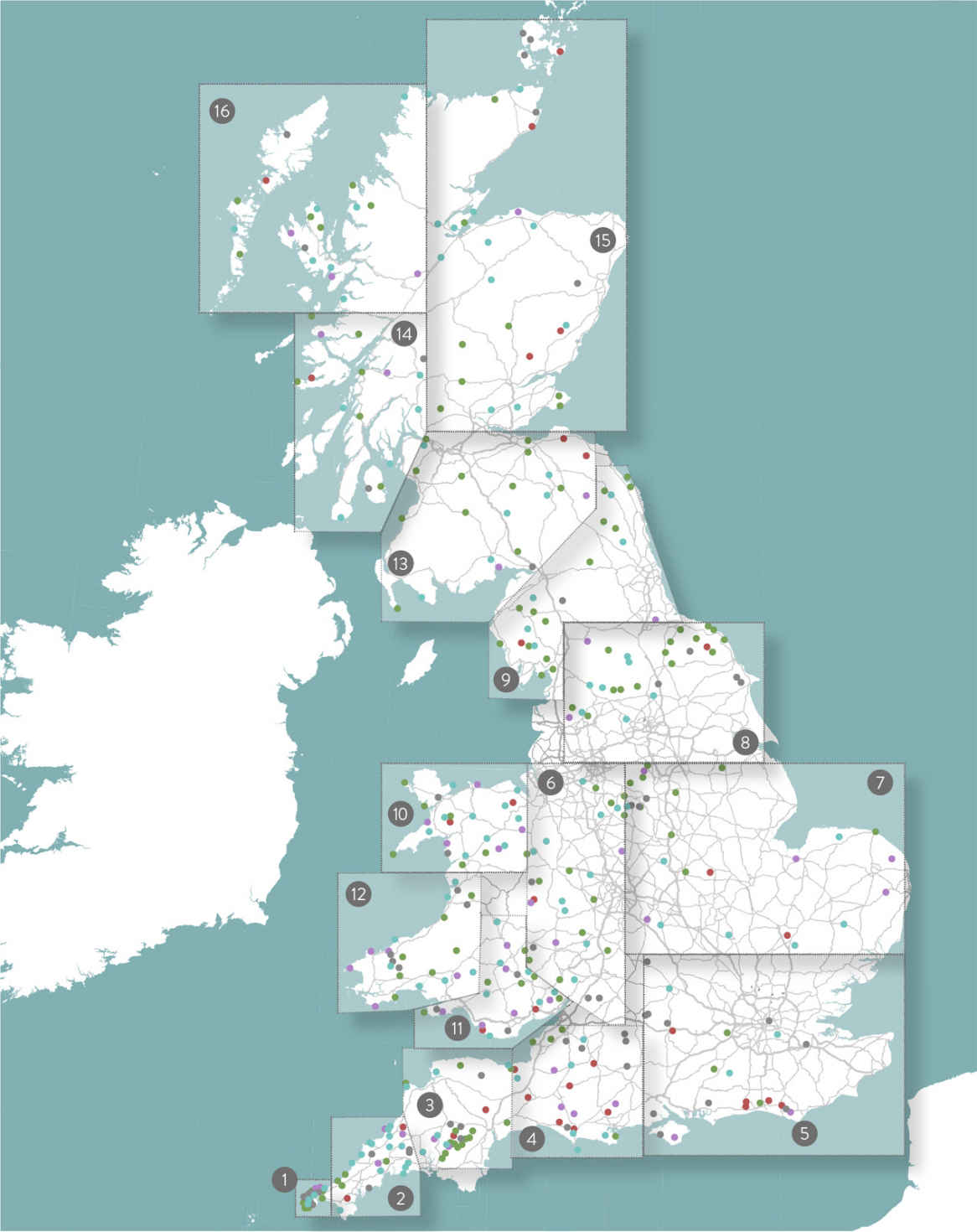

REGIONAL OVERVIEW

BRITAINS MAGICAL HISTORY

The folklore of the British Isles evolved out of the unique cultures of its inhabitants and their connection to the land and its supernatural beings and spirits.

The earliest visitors to these isles, once the ice sheets had receded, were Mesolithic hunter-gatherers. These nomadic people almost certainly followed an animist religion as many indigenous people still do today, seeing all of nature animals, plants, rocks, elements and heavenly bodies as alive and imbued with spirit, a spirit they felt themselves to be an integral and inseparable part of. It is also likely that these early people honoured Mother Earth, the Great Goddess, as one of the most powerful of spirits. They would have followed long hunting tracks through the wilderness, mapping out their journeys in songs and legends, each location along the way infused with meaning by their stories.

Later, the more settled farming cultures of the Neolithic and Bronze Age left behind their enigmatic monuments of stone and earth, including stone circles, dolmens, standing stones and barrows, many of which are aligned to the cycles of the sun and moon. Given the absence of written records the purpose and meaning of these structures were as much of an enigma to those who came after as they are to us, and some thought them the work of an ancient race of giants.

During the Iron Age, Celtic peoples inhabited the British Isles. Spread over numerous tribes they are collectively referred to as Ancient Britons. They spoke a version of the Celtic tongue known as Brythonic the ancestor of todays Welsh, Cornish and Breton languages and were ruled over by tribal chieftains and a scholarly elite known as the Druids, the keepers of ancient wisdom and arcane knowledge. These Druids wrote down none of their knowledge and they worshipped in sacred groves in the forest, so almost nothing survives of their temples or religion. All that remains are offerings cast into sacred springs and pools, and later stone carvings consisting of a number of basic inscriptions in their linear ogham script.

What little knowledge we do have of the beliefs and practices of the Ancient Britons comes down to us through the literature of the Romans, who were to become their conquerors. After invading the British Isles, the Romans set about eradicating the Druids who they saw as rivals, completely dismantling their power structures. However, the Romans were tolerant of Celtic beliefs, gods and religious sites, identifying the Ancient Britons gods as aspects of their own pagan deities. So for example the Celtic goddess Sulis at Bath (Aquae Sulis) became the Roman goddess Sulis Minerva. The Romans, too, made offerings at sacred springs and forest shrines, honouring the nymphs of the waters and the dryads of the woods, but they also worshipped their gods in dedicated stone temples.

During the Roman occupation of Britain, which lasted almost 400 years, Christianity arrived in the British Isles, and by the early medieval period it had evolved into a unique form known as Celtic Christianity. Yet after the Romans departed, Britain was plunged into a Dark Age as government structures collapsed, Roman towns and fortifications were abandoned, and the written historical record came to an end. Out of this darkness emerged some of Britains most colourful and enduring myths tales of King Arthur and his knights, the wizard Merlin and the Welsh bard Taliesin.

The Romano-British Celts, Romanised successors to the Ancient Britons, were at this time being assailed from all sides. From the east came the Angles, Saxons and Jutes, later to be referred to collectively as the Anglo-Saxons. The Scots-Gaels from Ireland advanced from the west and from the north came the Picts these two would later amalgamate to become the Scottish Highlanders.

A desperate rearguard action was being fought by the new Romano-British kingdoms against these savage invaders. Warlords like Arthur would achieve some victories and stem the tide for a while, but their fate was sealed and the Anglo-Saxons would eventually overrun the whole of the land that would become known as England. Only in Wales and Cornwall did the Ancient Britons endure and they also held onto the Lowlands of Scotland for some time until these were finally relinquished, going down in Welsh legend as the lost lands of the Hen Ogledd the Old North.

It is these Brythonic Celtic peoples who retained the original lore of the land of Britain and so were keepers of its ancient wisdom and folk knowledge. The Anglo-Saxon newcomers had less of a relationship with this new land and so imprinted upon it far fewer stories and legends than their Celtic neighbours. This is one of the reasons why there is such a dearth of folklore in the southeast of the country compared to the riches of the Celtic west. The flatter, more arable landscape in the east, its closer ties to the continent and its earlier modernisation are also likely to be contributory factors.

Cornwall is renowned for its wealth of unique folklore about giants, piskies, spriggans and knockers, for its abundance of holy wells and prehistoric sites, and for the birthplace of King Arthur at Tintagel. Wales, too, has its own fairy folk, the Tylwyth Teg and the shining beings known as Ellyllon. It is also the home of Myrddin Emrys (the Welsh Merlin), and produced an abundance of Celtic saints itinerant priests who travelled through Britain establishing hermitages and performing miraculous acts.