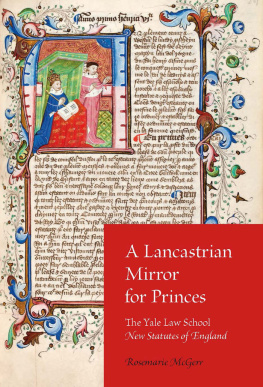

A Lancastrian Mirror for Princes

A Lancastrian

Mirror

for Princes

The Yale Law School

New Statutes of England

Rosemarie McGerr

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Bloomington & Indianapolis

This book is a publication of

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS

601 North Morton Street

Bloomington, IN 474043797 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

Telephone orders 800-842-6796

Fax orders 812-855-7931

2011 by Rosemarie McGerr

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

Manufactured in the

United States of America

Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

McGerr, Rosemarie Potz, [date]

A Lancastrian mirror for princes : the Yale Law School new statutes of England / Rosemarie McGerr.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-253-35641-3 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. England. Laws, etc. (Nova statuta) 2. Law England History To 1500 Manuscripts. 3. Great Britain Politics and government 13991485 Sources. I. Title.

KD130 1327C

349.42 dc22

2011007708

1 2 3 4 5 16 15 14 13 12 11

In memoriam

MICHAEL CAMILLE & JEREMY GRIFFITHS

And every statut koude he pleyn by rote.

GEOFFREY CHAUCER

Prologue to the Canterbury Tales

Preface

In the portrait of the Sergeant of the Lawe in the Prologue to Chaucers Canterbury Tales, the narrator includes the information that this pilgrim can cite every statute from memory an impressive professional credential, to be sure yet the irony of the passage might make us wonder what this accomplishment really means. We might expect that knowledge of all the statutes would increase a lawyers ability to solve a particular legal problem; but we might also wonder how knowledge of all of the statutes might shape a persons understanding of the relationship of the English monarchy and Parliament, as well as the history of particular laws and the concepts of justice that laws reflect. From the hundreds of medieval English statutes manuscripts that survive, we know that English lawyers often owned copies of the statutes; yet we also know that a growing number of readers in late medieval England who were not lawyers also owned copies of statute books. And we might ask, Why? A collection of medieval statutes may not seem like a very exciting kind of book to read; but a medieval manuscript of statutes may tell a very interesting tale. When the text begins with a narrative justifying an English princes removal of his father from the throne, we begin to recognize that a statute book might serve many purposes. Some of what engages us when we read such a manuscript, however, comes in the margins of the central text spaces where visual and verbal texts bring other voices into dialogue with the voices of the central text. Painted images, marginal comments, or ownership inscriptions may all come into play with the statutes, creating allusions to contemporary history, literature, or religious thought and revealing the cultural value the manuscripts earlier readers found within its covers.

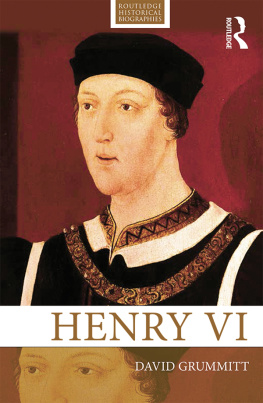

I first came across the Yale Law School manuscript of the New Statutes of England or Nova statuta Angliae when I was searching for manuscripts made for Henry VI of England, in hopes of finding additional work by the scribes and artists who produced a manuscript of The Pilgrimage of the Soul inscribed with Henry VIs name. While the Yale Nova statuta did not provide the kinds of leads I hoped to find, I nonetheless became intrigued by several aspects of this statutes manuscript. First among these were the manuscripts historical links with two very interesting women: Margaret of Anjou, Henry VIs consort, and Margaret Elyot, wife of the humanist author Thomas Elyot. While recent scholarship on Margaret of Anjou has allowed us to understand more about her actions and their context, none of the studies of this queen has taken into account what her connection to this copy of the New Statutes might reveal about her knowledge of English law or her construction of her role as queen. Especially if, as I hope my study demonstrates, Margaret did not receive the Yale manuscript as a wedding gift, but had it made as a gift for her son, the manuscript has much to tell us about the extent of Margarets participation in Lancastrian royal image-making. Less scholarship has focused on Lady Margaret Elyot (ne Margaret Aborough or Margaret Barrow), who was educated at the home of Sir Thomas More before she married into the Elyot family and came into possession of this manuscript. Knowledge of her link to this copy of the New Statutes adds greatly to our understanding of her adult life and the intellectual context in which Thomas Elyot composed his treatises.

Equally intriguing to me were the unique illustrations in the Yale Law School manuscript, which had not yet been fully reproduced, described, or analyzed. Although it is clear that this manuscripts texts and illustrations were produced by scribes and artists who worked on other copies of the New Statutes, the illustrations in this copy follow a different iconography from those found in the other surviving manuscripts, and these illustrations require a different form of reading process from what modern scholars might expect. To begin with, while the images of kings are portraits of the English kings whose statutes appear in the manuscript, the images borrow from discourses of justice and grace found in other visual and verbal genres to construct a commentary on kingship. The use of coats of arms in the margins of this manuscript also frames a reading of the statutes that is different from the readings suggested by the other surviving copies of the New Statutes. The Yale New Statutes manuscript thus demonstrates how medieval legal records could be framed in such a way as to inscribe multiple meanings and open the legal text to dialogue with works in other genres.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.