APPARITIONS OF THE SELF

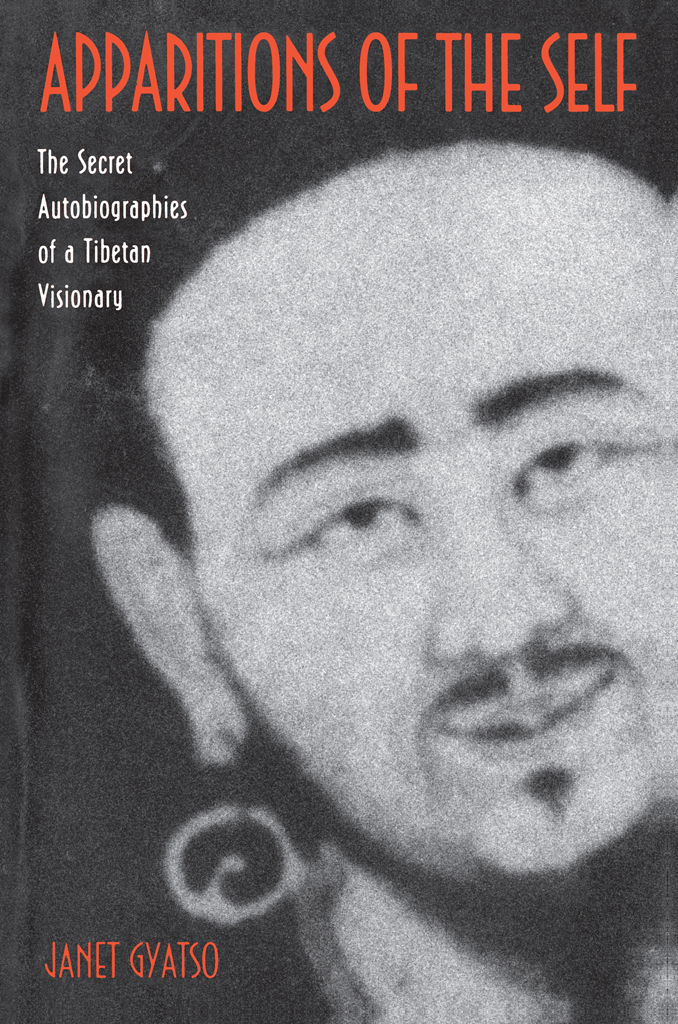

1. Jigme Lingpa. Painting in Tibet; provenance and owner unknown. The photograph was brought out of Tibet in the 1950s.

Apparitions of the Self

The Secret Autobiographies

of a Tibetan Visionary

A Translation and Study

of Jigme Lingpas

Dancing Moon in the Water

and

kkis Grand Secret-Talk

JANET GYATSO

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY

Copyright 1998 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

Chichester, West Sussex

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jigs-med-gli-pa Ra-byu-rdo-rje, 1729 or 30-1798.

[Gsah ba chen po nams sna gi rtogs brjod chu zlai

gar mkhan. English]

Apparitions of the self: the secret autobiographies of a Tibetan visionary ; a translation and study of Jigme Lingpas Dancing moon in the water and kkis grand secret-talk / Janet Gyatso.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-691-01110-9 (cloth : alk. paper)

eISBN: 978-0-69122-142-7 (ebook)

1. Jigs-med-gli-pa Ra-byu-rdo-rje, 1729 or 30-1798. 2. Lamas ChinaTibetBiography. I. Gyatso, Janet. II. Jigs-med-gli-pa Ra-byu-rdo-rje, 1729 or 30-1798. Klon chen si thig lei rtogs pa brjod pa dakki gsa gtam chen mo. English. III. Title.

BQ966.132965A3 1997

294.3923092dc21

[B] 97-10191

http://pup.princeton.edu

R0

Dedicated to the perduring brilliance of Tibetan civilization

Contents

ix

xi

xvii

xxi

xxiv

Illustrations

frontispiece

Preface

THIS BOOK takes a pair of texts, already esoteric in their traditional context, and draws them into the perilous domain of cross-cultural reflection. The texts, the secret autobiographies of the eighteenth-century visionary Jigme Lingpa, are of difficult access in their own right because of their complex locutions and allusions to arcane practices. In translating and explicating these, I have been generously assisted by several traditional Tibetan authorities, cited in the acknowledgments. This consultation, conducted over several years in North America and South Asia, provided me with an extraordinary opportunity to witness how a recondite literary genre like Tibetan secret autobiography is read and responded to by its intended audience: the bearers of the authors lineage and the practitioners of his teachings. Although my consultants live two centuries after Jigme Lingpa, they have participated in a world of religious practices and institutions that changed little from his day until the Chinese intrusion into Tibet in 1950.

Modern researchers need assistance from traditional authorities in studying many kinds of esoteric Tibetan Buddhist literature, but secret autobiography doubly requires such recourse. In addition to its abstruse content, there is the indirection of its discursive strategies, for it does not construct the sort of systematic structures or edifying narratives to which most scholars of Buddhism have devoted their attention. In fact, Tibetan autobiography has rarely been studied by modern scholars at all; the few academic discussions of this kind of writing are concerned largely with the information on names and dates that it happens to supply.

Autobiography is indeed a key resource for such data, but to see it only as that is to fail to recognize the genres other compelling features, features that have to do precisely with its unsystematic and subjective nature. Autobiography offers a view of how Buddhist traditions were embodied in the concrete social and psychological peculiarities of real persons, a view rarely gained from any other kind of writing. It is especially valuable for what it divulges of an individuals negotiation, via the medium of a text, of the discrepancies between normative ideology, social expectation, and personal desire.

But to ask these questions of a text takes the researcher beyond the emic reading, which is concerned largely with soteriology. It also takes her beyond the conventions of the philology and doxography of Buddhist studies. Secret autobiography, especially as artfully written as Jigme Lingpas, is fruitfully read as literature. A tropological analysis uncovers, for example, dissonances in the autobiographers self-image with respect to tradition that are never acknowledged overtly. Such analysis also reveals unanticipated complexity in the metaphysics of self-conception, beyond what is indicated in the doctrinal literature to which the autobiographer subscribes. I am even led to speculate that autobiographical self-figuration became in Tibet a new means to engage personal experience with normative doctrines like no-self and unformulatedness, doctrines that have never in the history of Buddhism named autobiographical writing as a recommended practice. Literary methods of analysis also help us to recognize direct connections between sociohistorical situations and what is written in a text, extending even to the question of the genesis of the genre of autobiography in Tibet altogether. And this in turn suggests ways to formulate what has been distinctive about Buddhism in Tibet, as compared to other Asian countries.

For me the most significant effect of submitting Tibetan Buddhist texts to untraditional modes of analysis is to bring this material into a broadly based discourse. Outside the Tibetan world, familiarity with Tibetan literature is limited to Tibetologists, a few other Asianists, and the circle of modern devotees of Tibetan Buddhism. This literature has yet to be considered in larger thematic terms, on a par with other objects of study in the humanities. Still relegated to the realm of the exotic and the mystical, Tibetan religion needs to be reevaluated in light of its very real historical and political actualities, not to mention its relevance to general discussions in ethics, the history of religion, philosophy, literature, anthropology, and many other domains. While the latter domestications cannot fail to alter, to some extent, the object under scrutiny, we can hardly argue that this object has ever been pristine or free from extrinsic influence in the first place. Given the beleaguered state of Tibetan culture today, it seems reasonable to assume that even a traditional exponent such as Jigme Lingpa would tolerate a certain distortion if that could facilitate an appreciation for the remarkable richness of his world.

To DISTINGUISH a Tibetan cultural product by bringing it into fields of discourse that render it comparable and contrastable to the products of other cultures benefits not only Tibetan Buddhists and those who would study them. It also impacts upon constituencies that have no intrinsic interest in Tibetan matters as such.

Western literary theorists and cultural historians have long held dear the existence of autobiography, along with a cluster of other factors, among them a sense of personal individuality, as unique markers of modern Western identity. While it is hardly the case that Tibetan autobiography matches Western autobiography in every respect, the fact that there exist notable family resemblances problematizes the reputed uniqueness of the latter. The study of Tibetan autobiography and its concomitant concepts of the person serves to correct the record, yielding a more complex picture of world literature and the place of Western representations of the self therein. While it has become imperative in recent years to focus upon difference, and thereby to curtail romantic projections of self upon the other, respect for the other also entails a recognition of practices that, despite undeniable differences, nonetheless accomplish purposes similar to those of Western cultural institutions.