Wisdom Publications

199 Elm Street

Somerville, MA 02144 USA

wisdomexperience.org

2022 Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photography, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system or technologies now known or later developed, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Thubten Zopa, Rinpoche, 1945 author. | McDougall, Gordon, 1948 editor. | Iseli, Peter, illustrator.

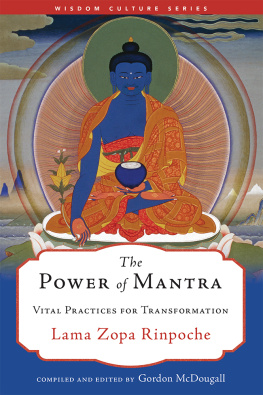

Title: The power of mantra: vital practices for transformation / Lama Zopa Rinpoche; compiled and edited by Gordon McDougall; paintings by Peter Iseli.

Description: First. | Somerville: Wisdom Publications, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021032862 (print) | LCCN 2021032863 (ebook) | ISBN 9781614297277 (paperback) | ISBN 9781614297437 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Buddhist mantras. | Mantras. | BuddhismTibet RegionPrayers and devotions.

Classification: LCC BQ5050 .T48 2022 (print) | LCC BQ5050 (ebook) | DDC 294.3/437dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021032862

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021032863

ISBN 978-1-61429-727-7 ebook ISBN 978-1-61429-743-7

26 25 24 23 22 5 4 3 2 1

Cover image by Peter Iseli. Cover design by Gopa & Ted 2 and Tony Lulek. Interior design by Tony Lulek. Photographs of Four-Arm Chenrezig , Tara , Solitary Vajrasattva , and White Tara are by Daniel Allemann. Photographs of Shakyamuni Buddha , Manjushri , Medicine Buddha , and the Thirty-Five Buddhas are by Peter Iseli. The photograph of Thousand-Armed Chenrezig is by Dominique Uldry. The photograph of Vajrasattva with Consort is by Elisabeth Zahnd Legnazzi. The photograph of The Seven Medicine Buddhas is by John Bigelow Taylor.

EDITORS PREFACE

T WO AND A HALF thousand years ago, a man became enlightened. Prince Gautama, Siddhartha, the son of the king the Shakyas, became Shakyamuni, the conqueror of the Shakyas, usually just known as the Buddha, the Awakened One.

Read one way, the story of the Buddha is of a person like us and his search for the truth, which culminated in his enlightenment under the bodhi tree. Read another way, the Mahayana way, he was already enlightened, and his life was a teaching, showing us exactly what we must do to become like him. Both readings are the truth. How that is so is a quest we ourselves must undertake to discover what it means for us.

And that is the same with the countless buddhas there are in Tibetan Buddhism. Why not just one Buddha, Shakyamuni? What does the plethora of buddhas mean? What exactly are they and how do they relate to our spiritual journey? I remember, in France in the 1990s, a student asked one of the great lamas, Are the buddhas real or imaginary? In a wonderfully enigmatic answer, the lama replied, Yes. Which I took to mean that its up to us to work it out.

Buddha, deity, meditational deity, yidam the terms are synonymous, all referring to the enlightened mind manifesting in a particular way to best benefit sentient beings. Thus, Chenrezig is the manifestation of the buddhas compassion, Tara is the manifestation of the buddhas enlightened activities, and so forth.

The many buddhas manifest according to the different propensities of different people. They are there to help us in whatever way we need, if we are able to open to them. Sometimes we need more compassion than wisdom; sometimes we need a more wrathful approach, other times a more peaceful one. We have a natural affinity for one or many buddhas. That does not mean that one buddha is better than the others, but that one will resonate with us more.

Each buddha has a mantra. A mantra is a series of Sanskrit syllables that evoke the energy of that particular buddha. All sound has energy. It is said that every Sanskrit syllable creates a sacred vibration in the mind, and so each syllable of each mantra has the power to alter our psychic nervous system in subtly different ways. Some mantras run smoothly through the mind and invoke peace and contentment, some seem difficult to pronounce and have a markedly different effect. A mantra works in two ways: externally as a sacred sound that carries a blessing, and internally as a tool to transform our mind into one that is more compassionate and wise.

When we take an initiation into a particular deity, we are generally given a mantra commitment, such as saying a certain number of mantras of that deity every day. Although to our Westernized, individualistic mind, this might seem like an imposition at first, in fact it is the gift of liberation. If we get into the habit of saying mantras whenever the mind slips into a dull neutrality or into emotive overdrivenot only when we are doing a daily meditation practice but whenever we are going about our businesswe can bring ourselves back to a peace and spaciousness that guards our mind from negativity. It is probably the most valuable mental tool we can have.

Generally, to practice a deity and say their mantra, we need an initiation given by a qualified teacher who is part of an unbroken lineage. There are some deities, however, who are so popular that their mantras are widely said by people whether they have had an initiation or not. Furthermore, even without an initiation, it is often permissible (and very beneficial) to do a simple version of that deitys practice. In such cases, it is generally said that rather than imagining yourself becoming the deity, as is often taught after initiationyou simply imagine them in front of you, and you receive the blessings of the deity.

By far the most popular mantra is that of Chenrezig (Avalokiteshvara in Sanskrit). There seems to be hardly a Tibetan person who doesnt constantly have OM MANI PADME HUM on their lips, and with non-Tibetans too, this is very popular. Chenrezig is compassion, which we all desperately need, so chanting his mantra is incredibly worthwhile.

Over the decades, Lama Zopa Rinpoche has given countless initiations and instructed his students to say many different mantras. For specific situations, he gives very specific instructions, telling us which mantra will best protect or help us. For instance, for the recent coronavirus pandemic, to protect themselves and others from the virus, he requested his students to chant the Vajra Armor mantra, a powerful healing practice.

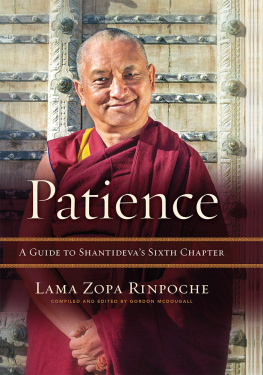

This book is a distillation of what Rinpoche has said of the most accessible deities and their mantras. These are the ones students of Tibetan Buddhism usually encounter first and practice longest, starting with Shakyamuni Buddha, the historical Buddha, the one who gave us the whole of Buddhism. Then, there is Chenrezig, the embodiment of compassion, Tibets most beloved deity and closely associated with his Holiness the Dalai Lama, and Manjushri, the embodiment of wisdom. The entire path to enlightenment is encapsulated in compassion and wisdom, and so these two buddhas are extremely important. So too is Tara, embodying the buddhas compassionate action. Then, after Medicine Buddha, the healing buddha, there are the mantras of the most effective purification practices, Vajrasattva and the Thirty-Five Confession Buddhas, and finally, the five powerful mantras Rinpoche often advises us to recite. Hopefully, this book will give you a feeling for the different deities and an appreciation of the power of the mantrasas well as the wish to use those mantras to transform your mind.

You might notice that there is not complete consistency in the way Tibetan terms are dealt with. Generally, Wisdom uses a simplified phonetic transcription that corresponds to the way the word sounds. However, because we have often used prayers from practices from Rinpoches Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition, such as the prayers to the Twenty-One Taras, in those instances we have kept with the FPMTs system. Similarly, we write the Sanskrit terms without diacritics, except in one appendix, where Lama Zopa explains the differences in the sounds of the mantras in detail. When Sanskrit and/or Tibetan terms appear in brackets, we have not specified which is which, because the two languages look quite different, but generally if both languages are together, the Sanskrit comes first.