Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Darden, Bob, 1954 , author.

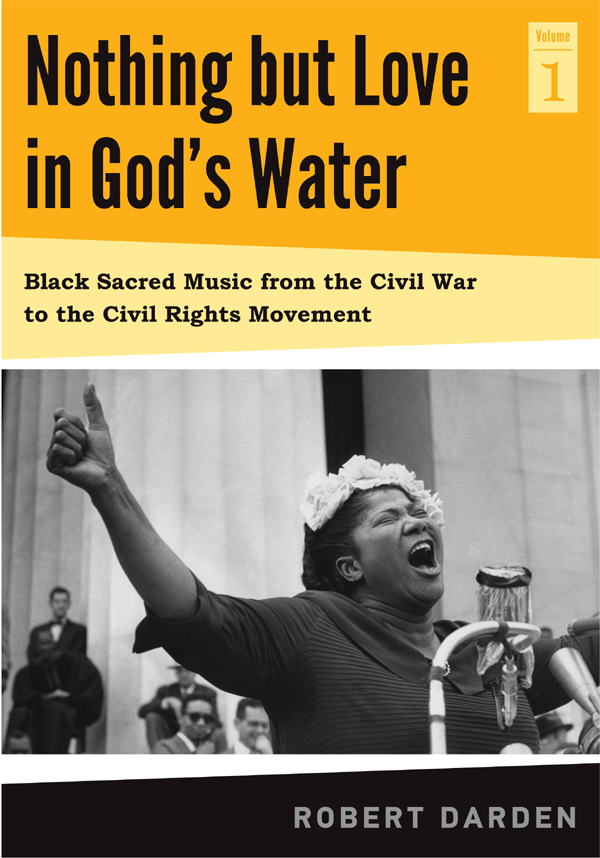

Nothing but love in Gods water / Robert Darden.

volumes cm

Summary: The first of two volumes chronicling the history and role of music in the African-American experience. Explains the historical significance of song and illustrates how music influenced the Civil Rights MovementProvided by publisher, Volume I.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Contents: Volume I. Black sacred music from the Civil War to the Civil Rights Movement.

ISBN 978-0-271-05084-3 (Volume I, cloth : alk. paper)

1. African AmericansMusicHistory and criticism.

2. Spirituals (Songs)History and criticism.

3. Gospel musicHistory and criticism.

4. African AmericansCivil rightsHistory.

I. Title.

ML 3556. D 33 2014

780.8996073dc23

2014018652

Copyright 2014 The Pennsylvania State University

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Published by The Pennsylvania State University Press,

University Park, PA 168021003

The Pennsylvania State University Press is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

It is the policy of The Pennsylvania State University Press to use acid-free paper. Publications on uncoated stock satisfy the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Material, ANSI Z 39.481992.

This book is printed on paper that contains 30% post-consumer waste.

Denied access to the political process, limited in what they could acquire in the schools and dehumanized in popular culture, black Southerners were compelled to find other ways to express their deepest feelings and to demonstrate their individual and collective integrity. What helped to sustain them through bondage and a tortured freedom had been a rich oral expressive tradition consisting of folk beliefs, proverbs, humor, sermons, spirituals, gospel songs, hollers, work songs, blues and jazz.

LEON LITWACK

I really did like the way you started off this meeting with song. It reminded me that when I was a youngster working in the logging camps of Western Washington, Id come to Seattle occasionally and go down Skid Road to the Wobbly Hall, and our meetings there were started with a song. Song was the great thing that cemented the IWW together.

HARVEY OCONNOR

Just as I was beginning to write this book, pro-democracy uprisings in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya erupted and spread across the Middle East. At the time, I had no idea where those spontaneous heart-cries for freedom would lead, but it made for a compellingand eerily familiarbackground from which to write. In the midst of this, I reread Zora Neale Hurstons chapter on High John de Conquer in The Sanctified Church:

High John de Conquer came to be a man, and a mighty man at that. But he was not a natural man in the beginning. First off, he was a whisper, a will to hope, a wish to find something worthy of laughter and song. Then the whisper put on flesh. His footsteps sounded across the world in a low but musical rhythm as if the world he walked on was a singing-drum. Black people had an irresistible impulse to laugh. High John de Conquer was a man in full, and had come to live and work on the plantations, and all of the slave folks knew him in the flesh.

The sign of this man was a laugh, and his singing-symbol was a drum. No parading drum-shout like soldiers out for show. It did not call to the feet of those who were fixed to hear it. It was an inside thing to live by. It was sure to be heard when and where the work was hardest, and the lot the most cruel. It helped the slaves endure. They knew that something better was coming. So they laughed in the face of things and sang, Im so glad! Trouble dont last always. And the white people who heard them were struck dumb that they could laugh. In an outside way, this was Old Massas fun, so what was Old Cuffy laughing for?

Old Massa couldnt know, of course, but High John de Conquer was there walking his plantation like a natural man.

You never know how or when the threads of your lives intertwine. I have written three books in recent years and, upon reflection, I see that they are interrelated: People Get Ready!: A New History of Black Gospel Music; Reluctant Prophets and Clueless Disciples: Understanding the Bible by Telling Its Stories; and Jesus Laughed: The Redemptive Power of Humor. And now with the first volume of Nothing but Love in Gods Water, Black Sacred Music from the Civil War to the Civil Rights Movement, I see where they all connect. Theyve all helped prepare me for this moment.

I wrote People Get Ready because gospel music has been part of my life. I wanted to know more about it, about how it all fits together. I wrote Reluctant Prophets, in part, because story is at the heart of everything I write and teach, fiction and nonfiction. Story was at the heart of People Get Ready. I wrote Jesus Laughed in part because of the visits Mary and I had made to black churches in the course of writing People Get Ready. Black churches resound with laughter before, during, and after the services in a way that the white churches Ive attended do not. Where did we lose that capacity to laugh? Ive written Nothing but Love in Gods Water in part because of the ways black sacred songfrom the spirituals through the union movements through the civil rights movementhas continued to irrepressibly bubble up and envelop black people at their times of greatest need... as if this music is always there, always available, always waiting for a moment like this.

And now I stumble across Zora Neale Hurstons essay on High John de Conquer, a magical, mythic black figure who predates John Henry and Stagger (or Stack-o) Lee. High Johns weapons are laughter and song. And speed. High John is fast, as Hurston writes, Maybe he was in Texas when the lash fell on a slave in Alabama, but before the blood was dry on the back, he was there. A faint pulsing of a drum like a goat-skin stretched over a heart, that came nearer and closer, then somebody in the saddened quarters would feel like laughing and say, Now High John de Conquer, Old Massa couldnt get the best of him. That old John was a case! Then everybody began to smile.

Back in the present, Im astounded as New York Times reporters and BBC commentators remark time and time again at the speed with which the messagethe storyof the youthful protestors spreads within their countries and across the Middle East. The social media have added new wings to the feet of High John, it seems.

Armed with that image, I see now that Nothing but Love in Gods Water is ultimately about storya story that came from Africa that sustained the slaves and their descendants for generations. Its about songsongs that came from Africa and enveloped the best of the Christian faith and withstood the dogs and water cannons in Birmingham. And its about laughterthe laughter that came from Africa and enabled blacks in the Jim Crow south to secretly laugh at those who spent most of their waking moments trying to figure out ways to crush High John and the millions like him. It is no accident, Hurston writes, that High John de Conquer has evaded the ears of white people. They were not