Table of Contents

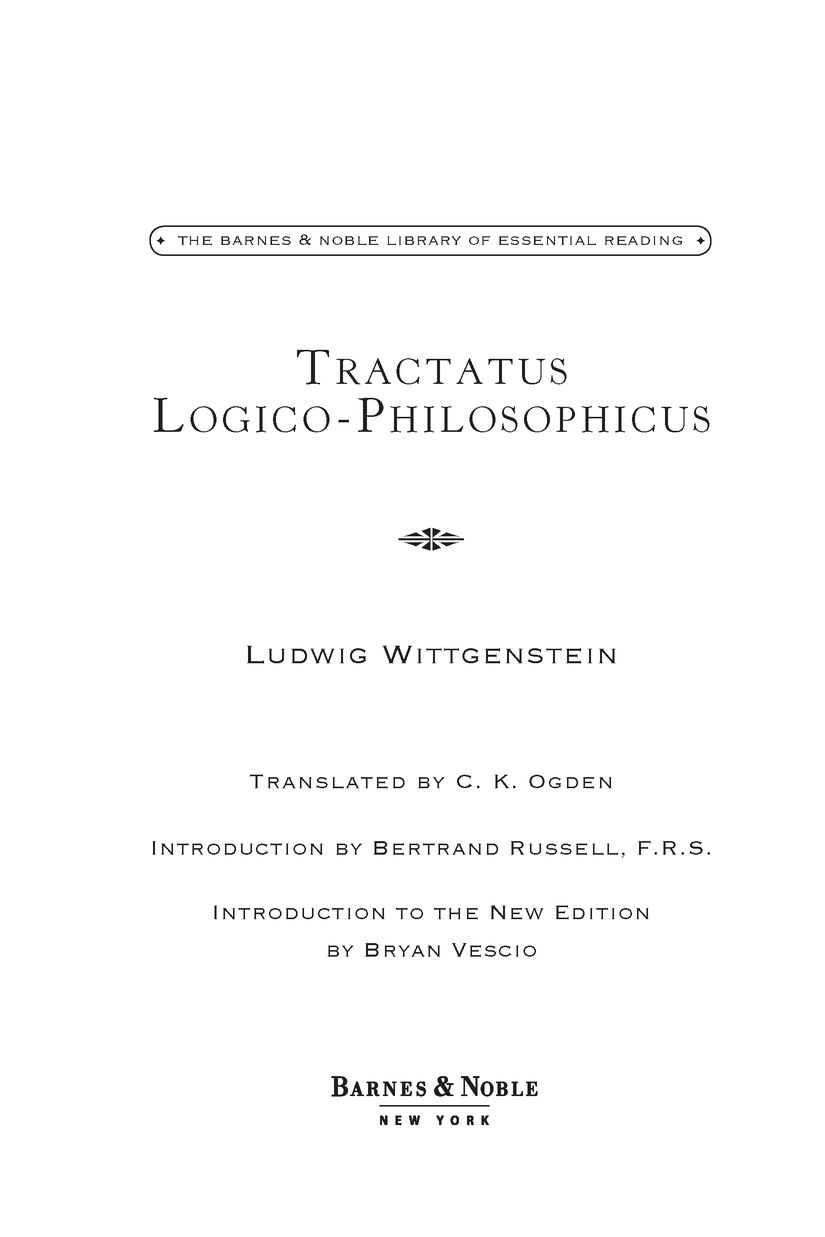

Introduction and Suggested Reading 2003 by Barnes & Noble, Inc.

Originally published in 1922

This 2003 edition published by Barnes & Noble, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7607-5235-7 ISBN-10: 0-7607-5235-4

eISBN : 978-1-411-42863-8

Printed and bound in the United States of America

5 7 9 10 8 6

EDITORS NOTES

IN RENDERING MR. WITTGENSTEINS TRACTATUS LOGICO-PHILOSOPHICUS available for English readers, the somewhat unusual course has been adopted of printing the original side by side with the translation. Such a method of presentation seemed desirable both on account of the obvious difficulties raised by the vocabulary and in view of the peculiar literary character of the whole. As a result, a certain latitude has been possible in passages to which objection might otherwise be taken as over-literal.

The proofs of the translation and the version of the original which appeared in the final number of Ostwalds Annalen der Naturphilosophie (1921) have been very carefully revised by the author himself; and the Editor further desires to express his indebtedness to Mr. F. P. Ramsey, of Trinity College, Cambridge, for assistance both with the translation and in the preparation of the book for the press.

C. K. O.

1922

For the reasons stated above, this Barnes & Noble edition maintains the dual-language format of the original.

INTRODUCTION TO THE NEW EDITION

LUDWIG WITTGENSTEIN IS WIDELY REGARDED AS THE MOST important philosopher of the twentieth century, and the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus is the only book-length work of philosophy he published in his lifetime. Together, these two facts convey some idea of the power this work has exerted over the minds of other philosophers and over the discipline itself. In the book, Wittgenstein claims no less than to have solved all the problems of philosophy, and for a work with such a short page count, it is astonishing in its ambition. It manages to offer a radical new theory of logic, along the way addressing such problems as the foundations of mathematics, solipsism, the nature of ethics and art, and even free will. All these topics are confronted in an intricately structured series of numbered statements that are notoriously accompanied by little argument, but that are nevertheless commanding in their declamatory tone and even beautiful in their gnomic brilliance. By the end of this treatise on logic, the book takes a striking turn toward the mystical, and this shift indicates the somewhat conflicted attitude toward philosophy that lies at its core.

Ludwig Wittgensteins life was marked by the same pervasive sense of conflict that characterizes his work. He was born in 1889 into the family of a wealthy Viennese industrialist but gave the bulk of his inheritance away. He was both Jewish and homosexual in a time and place that accepted neither. The youngest of eight gifted children who grew up in an exceptionally cultured household, Wittgenstein at first seemed to lack the talents of his older siblings, particularly in music. He was sent to study engineering, and eventually went to Manchester, England, to study aeronautics. During this time he became interested in the theory of mathematics and began reading the works of Gottlob Frege and Bertrand Russell, who had independently been trying to prove that mathematics is a branch of logic. He decided to share his own ideas on the subject with Frege, who suggested that he go to Cambridge to study with Russell. At Cambridge, Russell quickly became convinced of Wittgensteins genius and encouraged him to develop his own theory of logic, which Wittgenstein began to do in Norway until World War I broke out. An Austrian patriot, Wittgenstein enlisted on the opposite side of the war from Russells England, and it is both incredible and appropriate that he was able to complete the Tractatus, his theory of logic, during active combat duty. It was published in 1921. After a brief stint as a rural schoolteacher, Wittgenstein returned to Cambridge and eventually received an appointment as professor. He became legendary for his eccentric behavior and lectures, but in these lectures Wittgenstein developed an entirely new approach to philosophy that departed sharply from his work in the Tractatus. This approach culminated in the posthumous publication of his Philosophical Investigations (1953), the other major work on which his reputation now rests. But he found academic life to be incompatible with his work, and he resigned from Cambridge in 1947, only eight years after he was appointed to G. E. Moores chair. He died of prostate cancer in 1951.

The Tractatus was written in three distinct stages, each of which produced one of the books major contributions to philosophy. In 1913 -14, Wittgenstein worked in a remote village in Norway to develop his theory of logic. This theory is formulated explicitly in response to Russells Theory of Types, arguing that a properly conceived symbolism makes the latter superfluous. During the first months of the war, in which Wittgenstein saw no combat, he developed his Picture Theory of Propositions, which held that propositions represent states of affairs in the world because their parts mirror objects and relations in the world itself. On this theory, it is a common form or structure that propositions share with the facts they represent, and it is this form or structure that logic captures. After 1916, when Wittgenstein began to experience combat first-hand, he became suicidal, as he frequently did throughout his life, and he turned to religion for consolation. This conversion is largely responsible for the mysticism that fills the final pages of the Tractatus, which holds that science and language must remain silent on the ultimate truths about the world, including those of metaphysics, ethics, and aesthetics.

It is remarkable that these apparently distinct ideas are blended into a seamless whole in the Tractatus, and what unites them is Wittgensteins central distinction between saying and showing. According to Wittgenstein, language can only describe facts about the world, not the logical structure that it shares with those facts. For to describe the latter would be to describe the very limits of the world, and that can only be done from an unattainable position outside the world. The logical structure that undergirds our languageand thus, for Wittgenstein, that defines our worldcannot be described at all; rather, it can only be shown, and it is shown everywhere in language that is used properly. Mysticism, which Wittgenstein defines as feeling the world as a limited whole, is a kind of knowing beyond prepositional knowledge, a sense that even though the limits of the world cannot be said or thought, those limits nonetheless exist. But this leaves philosophy, whose goal is precisely to describe those limits, in a peculiar position. Wittgenstein considers all the problems of philosophy to stem from an attempt to say what can only be shown. All positions in metaphysics, ethics, and aesthetics, as statements about the limits of possibility in the world, are fundamentally in error. Once this becomes apparent, Wittgenstein thinks, all the problems of philosophy are solved in the sense that they are all dissolved. Yet the