To Roel and Marleen, with thanks for help

To Maggie, with love

Contents

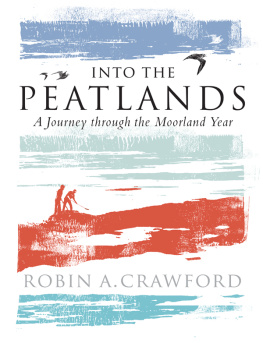

For a moment he thought of returning lest he should get lost in the space of the moor, but some daring instinct, some sense of adventure, was urging him onwards from the houses anchored to their familiar earth. It was as if he was Columbus setting off into a new world with inadequate maps, charts that showed only dimly and tentatively unknown seas and unknown islands.

On the Island , Iain Crichton Smith

PASSING

(from an Irish proverb)

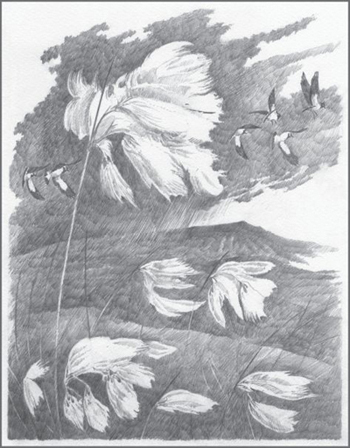

The child arrives, weighty as a creel filled with peat,

for many years, providing warmth and heat,

till he or she departs, light and insubstantial as white

wisps of smoke rising from a fire banked up late at night.

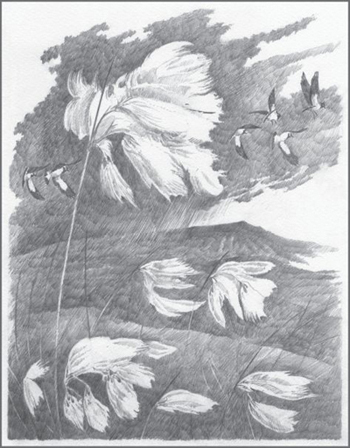

CAMOUFLAGE

The eye can be deceived by flowers

bright upon the surface. They bloom

for say a season, conceal the toughness of the limbs

digging deep below. Each plumes

a small deception, as men find out when they exhume

and unearth heat from damp and cold

for heather knots as tight and hard as briar,

each flare of purple like a rose

spilling out from thorns

disguising the resilience

of how its grip clings to soil and stone

through the bushwhack of each storm.

I grew up on a green spit of land, with acres of emptiness on either side.

Behind our house on the Isle of Lewis there was the width of the Atlantic. Only around three-quarters of a mile separated it from the back of our byre, a tractor trail running down to the shoreline through the centre of our narrow strip of croftland. Green stalks of oats, crops of potatoes and turnips guarded you along the way. A cow or some sheep peered as you passed. Looking out from a flat, stony edge of land, one we called the cladach, differentiating it from the green, fertile soil of the machair a few miles to the north, there was little to be seen a plinth of rock called Sgeir Dhail (Dell Rock) on which a herd of seals sometimes settled, making known their presence by a cacophony of loud, assertive honks; the curl of the Butt of Lewis with its red sandstone lighthouse; a few gulls and gannets, shags and cormorants, the last slinking below seawater, all sleek and black. There were times I would stand on tiptoes and dream I saw Newfoundland in the distance far to our west, its place names like a litany of prayer I had stumbled across in a book. I would pretend I could pinpoint where they were with my finger, stabbing into the vacancy:

Old Bonadventure Kettle Cove Hearts Content Swift Current

Their names were all so much more poetic and exotic than the place names of the villages of Ness all around me. South Dell Cross Skigersta Swainbost Adabrock Only the township of Eoropie in the far north possessed the breadth and expansiveness that I heard in those places on the far side of the Atlantic, as if somehow it was less cramped and confined than its appearance might suggest, holding a continent within its borders, a vowel or two misplaced in its search for Europes vast entirety.

There were times I needed that sense of belonging, of not being isolated from the world. Our house faced a similar kind of emptiness to the one I witnessed in the width of the sea. The only difference was that it retained a flat calmness, even on days when the wind stirred up the ocean. Only one or two breakers broke the surface. Closest to our home, Beinn Dail (Dell Mountain) was like The Great Wave off Kanagawa , created by the Japanese artist Hokusai in a wood print in the early nineteenth century. It, however, was more of a rogue wave than a tsunami and one that would do little damage to either man or the environment. Its tiny 170 yards in height were unlikely to threaten either the empty land below or South Dell in the distance if it ever fell or toppled, casting rock or peat from its summit. Another hill, Mirneag, was the equivalent of Mount Fuji in that portrait, peering over Beinn Dails edge. Again, at just 271 yards in height, it was miniature, only attracting attention because of the horizontal nature of much of its surroundings. Looking up from the depths of a bog, it seemed large and looming, an Everest dominating the scene.

Yet despite its lack of dizzy, death-defying heights, our moor was an intimidating landscape. There were miles when little could be seen but chains of bogs and still black pools; low hills; outcrops of heather; obstacles to anyone who wished to progress across its acres. When I tried once or twice to walk across to the village of Tolsta on the opposite side of the island, that motionless, flat landscape which at first glance seemed short in terms of distance became huge and as expansive as the ocean. There were occasions, too, when I might roll and reel, as if I were on a sea voyage. Feet could slip and slide, tumbling towards a pool of water. The heather ridges seemed to mount up before me, crest upon crest, forming insurmountable barriers. There was a maze-like quality about walking across its breadth. You could easily stumble across your own steps, crisscrossing the moorland in endless, decreasing circles. This meant that people could become lost, either in mist or blizzard. The last was a fate that occurred, for instance, to three young men, Allan Campbell, John Macritchie and Angus Morrison, way back in December 1883. They were found some six miles from their home in the village of Lionel, dead from cold and exhaustion.

It is for this reason that, wherever you go on the Lewis moor, there are often cairns of stone or slabs of rock upended, markers for a route that it might be advisable for a person to take or even to indicate where a person might gain some perspective on his place and position in that austere world. My great-grandfather, nicknamed Stuffan after Stephen in the Bible, hefted a pinnacle of stone on his back and placed it deep within the peat on the Dell moor. There were others who did this too, guides and navigators who provided pinpoints of light, pinnacles of Lewisian gneiss by which people could see their way across this nondescript landscape. They were also according to a friend of mine likely to have laid paths too, especially in areas that were well used by them, between the stone, tumbledown walls of sheilings, small patches of pasture. Nowadays, the paths stretch unseen, concealed by moss or heather.

There were human dangers on the moor too. Even as relatively late as the last years of the First World War, when so many of our dear ones and best manhood [were] laying down their lives for King and Country, the crofters of my native village South Dell petitioned Sheriff Substitute Dunbar in the Burgh Court in Stornoway about the actions of a man called Norman Macdonald. This individual was apparently employed as a gamekeeper in Galson Farm at that time the only large working farm that bordered the district. Claiming he was a source of danger, they noted he had shot a gun in the direction of a young lad called William Murray someone I knew as an old man and one of the church elders for having a rabbit in his possession which the dog he had with him killed accidentally. Two weeks before that, he had pointed his gun point blank [at] another man from this township on the public road. He had also threatened people and been convicted for assaulting a young boy on the shoreline. It was little wonder that the very children [were] afraid for their lives, fearing that this individual will meet them when they are herding the cattle or looking after their sheep on the moor. They followed a maze-like path to avoid Macdonald, looking out for his presence looming in their direction as he came across the moor.