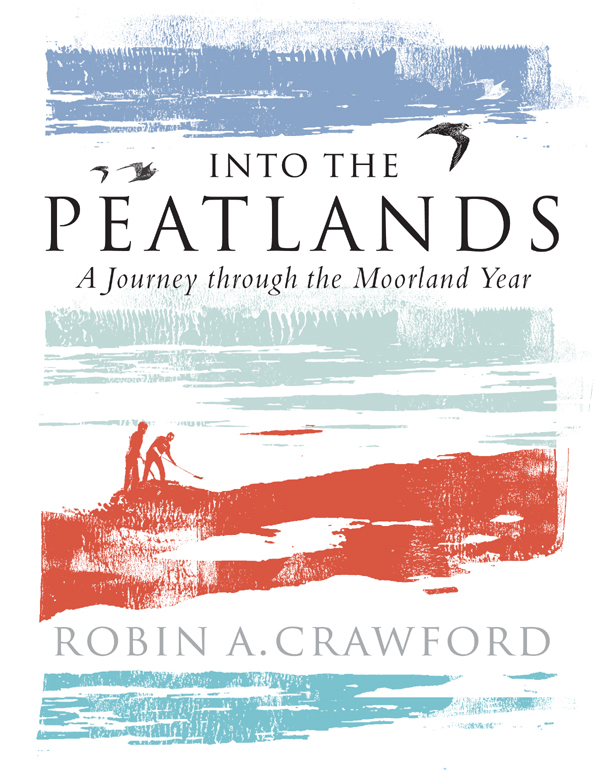

INTO THE

PEATLANDS

First published in 2018 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Text and original artwork

copyright Robin A. Crawford 2018

The moral right of Robin A. Crawford to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978 1 78027 559 8

eBook ISBN: 9781788851404

British Library

Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Mark Blackadder

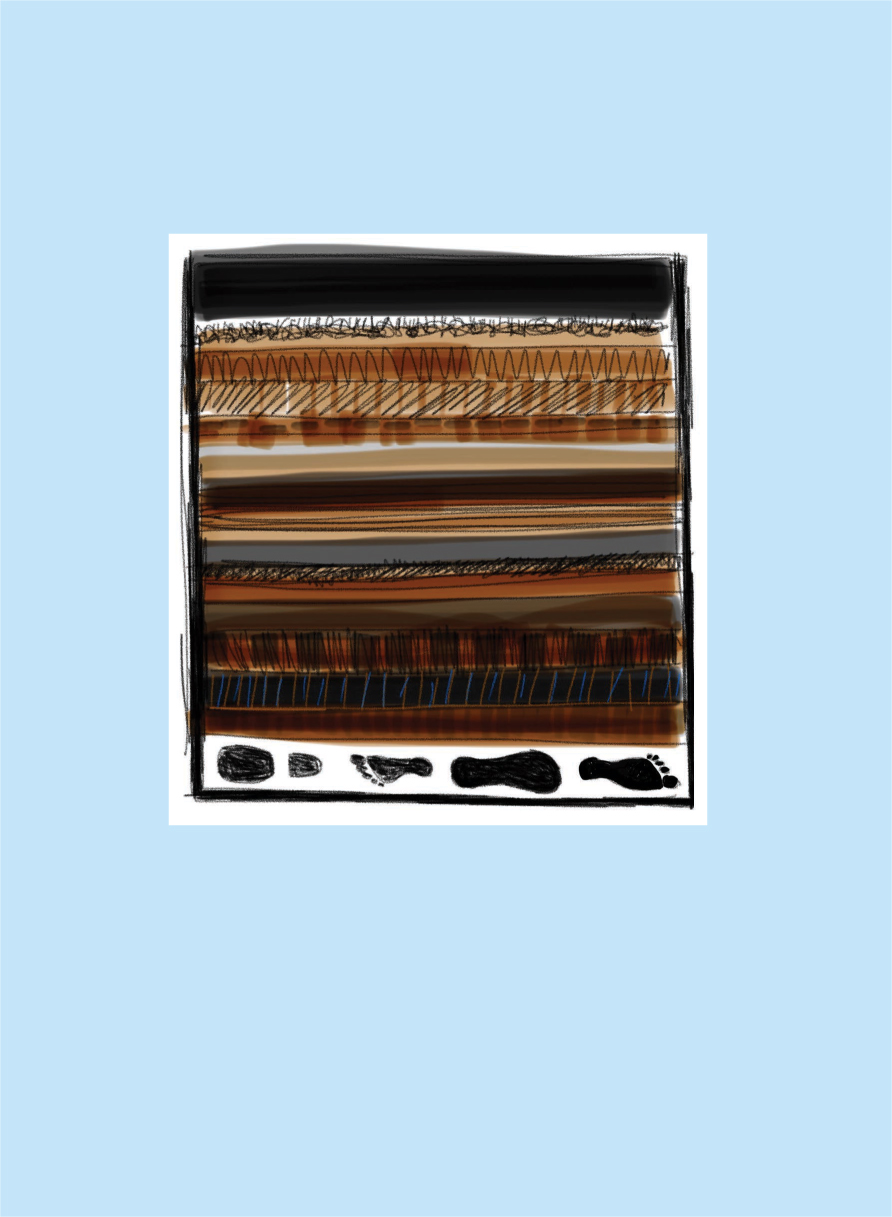

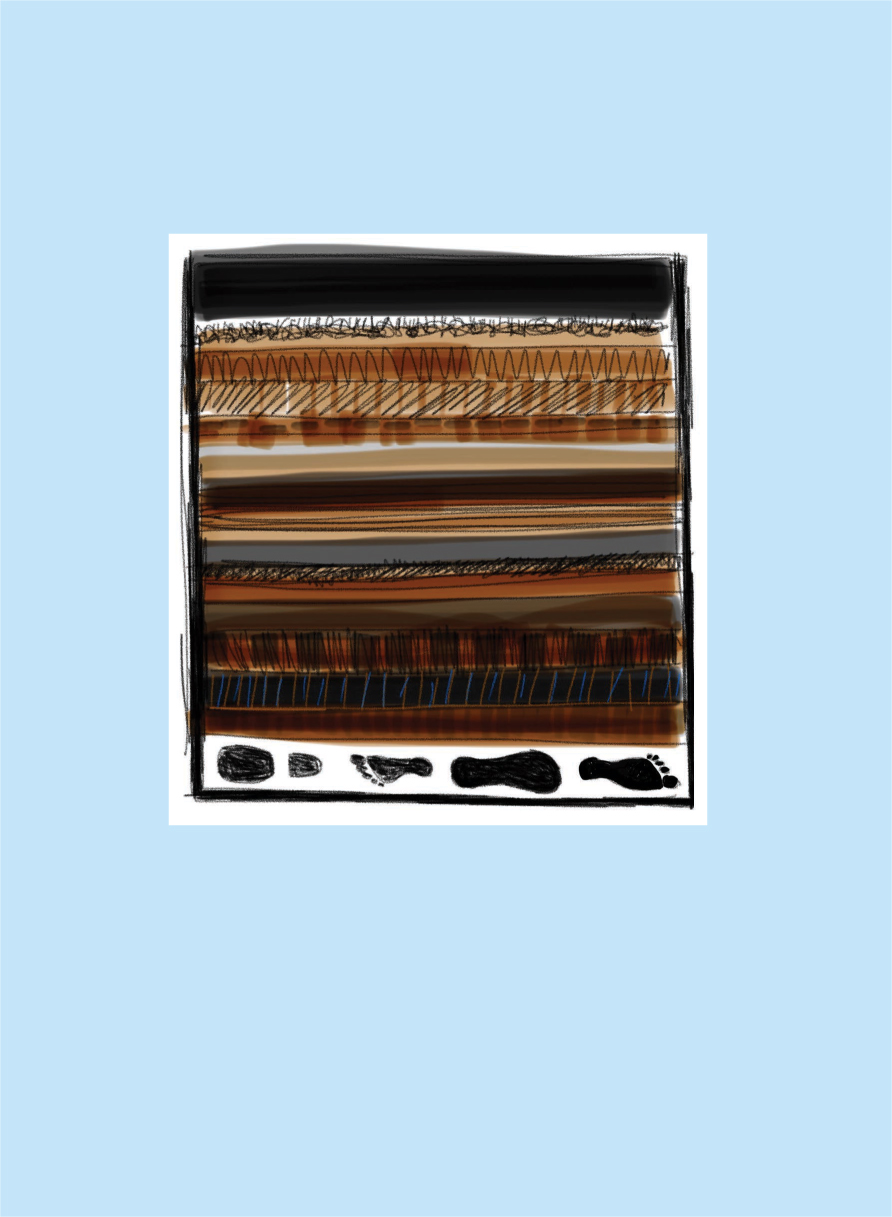

Illustration p. ii: Peatbank Strata with Footprints.

Printed and bound by PNB, Latvia

Dedicated to Pam and Joe Crawford

Man looks aloft, and with erected eyes Beholds his own hereditary skies.

Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book 1 (as translated by John Dryden)

Contents

List of Plates

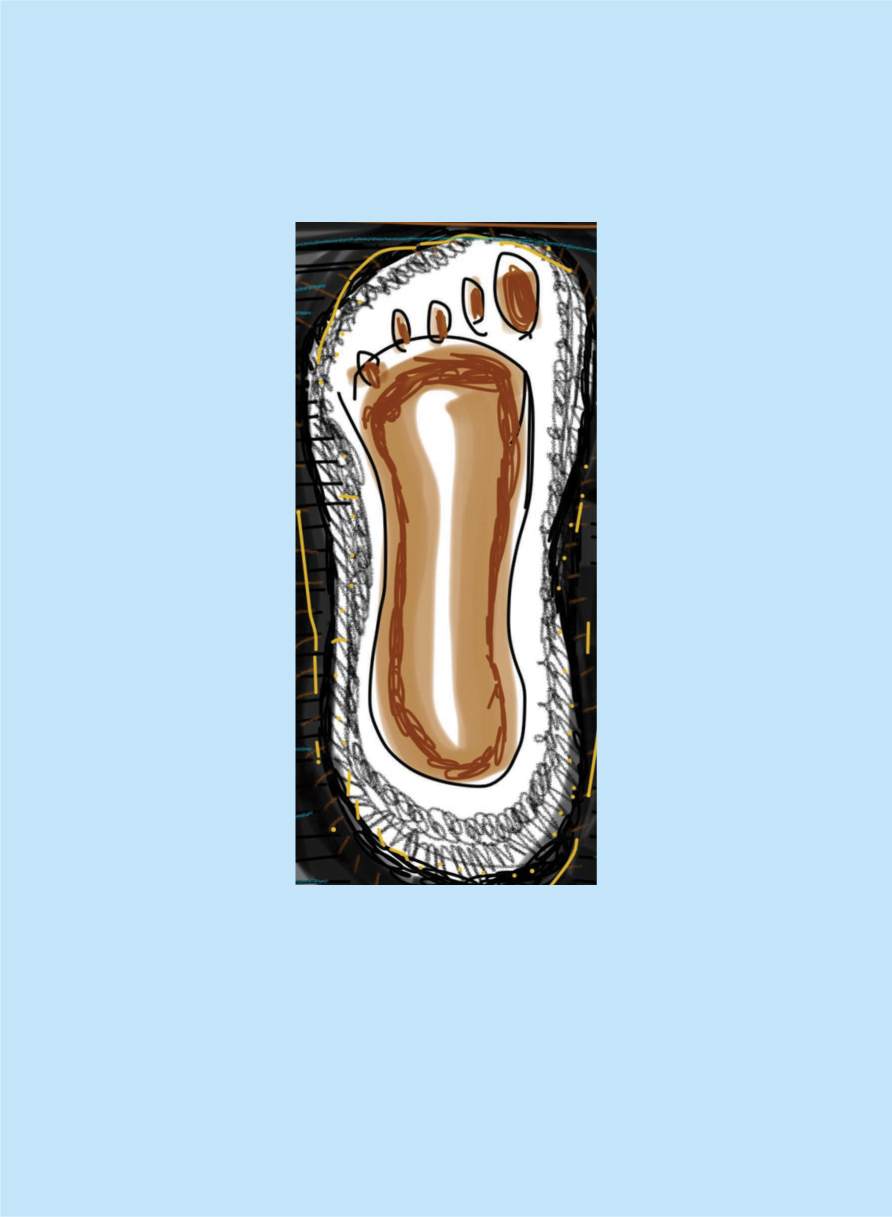

Peat Footprint.

Introduction: A Leaving

Angus Gillies is just one of hundreds of thousands, probably millions, who have emigrated from the peatlands of Scotland. He was born about 1860 on the Hebridean island of Lewis, but like so many before and since he sought a new and better life far away on the other side of the Atlantic. It was an ocean he knew well; twice a day it would either softly wash up the islands beautiful white sandy beaches sparkling luminously turquoise, or crash mercilessly against the ancient rocky cliffs, threatening destruction sometimes both.

Angus (Aonghas an Gillies in the Scottish Gaelic his people spoke) grew up in Kirkibost, a township of small, self-sufficient farmsteads or crofts on the Atlantic seaboard, and must have gazed over the ocean all his life. People had been living a similar lifestyle on its edge since at least the Iron Age 3,000 years earlier and probably for longer growing a few crops, pasturing their livestock on the islands vast moors, taking what they could from the sea and shore. But by the mid-nineteenth century that way of life was under threat as never before and, like so many across the Scottish peatlands, islanders were drawn or forced out to the ever-expanding industrial towns and cities of the mainland, to the central Lowlands, London, the Americas and across the British Empire in the hope of a better life. They were victims of a society in flux, experiencing massive social changes following the Industrial Revolution, fleeing poverty, famine, family feud, clearance, dictatorial landlords, oppressive tradition and constricting religion. It was a huge risk to leave for life on the other side of the world, and for some it was fatal, but to stay would have been impossible. So, aged about twenty, he left. Never to return.

More than a century later Marion Laitner, an American, aged ninety, visited Kirkibost. Through family history research she had discovered that she had second, third and fourth cousins living there and as she was reaching the end of her long life she wanted to see the place where her people had originated and the setting for so many of the tales passed down to her. She was welcomed as so many are with the generous hospitality of the island and the joy of family reunited, but a further surprise was in store. She was taken out onto the moor where the family had for generations cut the thick, muddy peat to burn as fuel. At a particular spot the top turf was removed for her and there, preserved in the peat, was a footprint it was the footprint of her father, Angus Gillies.

As she placed her own foot beside the preserved print her cousins explained that on the day before he left his mother had given him a creel and sent Angus out to the bank to collect some peats. Then he was off, like so many of the young islanders. She was desolate at his leaving, but she had to cope the best she could. Life went on.

On her next trip out to the peat bank to collect fuel she discovered one of his footprints there. As the only memento she had of her son she covered the print with turf, and after she died new generations of the family preserved the footprint until that day more than a century later when his daughter returned to her fathers homeland.

* * *

Anguss footprint is not the only one out on the moor. There are prints of other Atlantic emigrants, not always man-made, like those of the white-fronted goose, which leaves the moorlands of the islands for Greenland each spring, or the rasping corncrake, which heads back to Africa in the autumn.

Alongside these are the more recent human footprints preserved at the foot of most worked banks where people in the north and west of Scotland still cut peat for fuel. Among those at the foot of many a peat bank are mine. It has been my passion to try to understand what it is about peat that makes it such a special ingredient in the making of Scotland.

My journey began when I married Angie, who grew up on Lewis. Since then we have returned most years and I have grown fond of the island and its people. I have always been fascinated by built structures in the Scottish landscape standing stones, subterranean souterrains, cairns, icehouses, water towers, sheep fanks, hydro-electric dams, Roman walls. On Lewis, the peat stacks and cut peat banks are an integral part of the islands culture. Layers of peat slabs, layers of history.

The peat itself is built on its own history, ever changing but still the same. So is the peat stack. It is in a constant state of metamorphosis. From its late summertime construction, slabs are removed daily until it has disappeared, leaving only a dark peaty crumble shadow of its former self. In not a few cases in the peatlands that place has been where the stack has stood for generations, with the people constructing it changing but the family, the home, remaining constant each daughter and son McLeod, upon NicLeod, upon Mcleod. Come spring and the process of resurrection begins again. In the short months between May and early August the peat is cut, dried, transported and stacked before the long, claustrophobic peatland winter begins.

Peat is a fuel created by water, dried into a solid, turned into a gas alchemically but it is also a preserver, an organic time machine. It hasnt only conserved Anguss footprint but also the microscopic pollen grains from millennia ago which were captured in the peats formation. They can tell us about ancient peoples first felling of trees to create agricultural land.

Peat is burnt and turns to ash in the hearth, but miraculously it holds within itself the ashen fallout from Icelandic volcanoes cooked in the belly of the earth, then carried south on the wind; ash from the burning of the forests on Lewis by the Vikings; ash from the peat set alight on Lochar Moss by a spark from a nineteenth-century steam locomotive; ash from Russian peat-fired power stations; or coming full circle ash from peat fires raging uncontrollably in Indonesia caused by farmers slashing and burning forest land to feed an ever growing world population.