Table of Contents

Also by the author:

Drawing on the Artist Within

To the memory of my father,

who sharpened my drawing pencils

with his pocketknife

when I was a child

Acknowledgments

FIRST, I WISH TO WELCOME my new readers and to thank all those who have read this book in the past. It is you who make this twentieth-year edition possible by your loyal support. Over the past two decades, I have received many letters expressing appreciation and even affection. This shows, I think, that in this electronic age, books can still bring authors and readers together as friends. I treasure this thought, because I love books myself and count as friends authors I have never met except through their books.

Many people have contributed to this work. In the following brief acknowledgment, I wish to thank at least a few.

Professor Roger W. Sperry, for his generosity and kindness in discussing the original text with me.

Dr. J. William Bergquist, whose untimely death in 1987 saddened his family, friends, and colleagues. Dr. Bergquist gave me unfailingly good advice and generous assistance with the first edition of the book and with the research that preceded it.

My publisher, Jeremy Tarcher, for his enthusiastic support of the first, second, and now the third edition of the book.

My son, Brian Bomeisler, who has so generously put his skills, energy, and experience as a artist into revising, refining, and adding to these lessons in drawing. His insights have truly moved the work forward over the past ten years.

My daughter, Anne Bomeisler Farrell, who has been my best editor due to her understanding of my work and her superb language skills.

My closest colleague, Rachael Bower Thiele, who keeps everything on track and in order, and without whose dedicated help Id have had to retire years ago.

My esteemed designer, Joe Molloy, who makes superb design seem effortless.

My friend Professor Don Dame, for generously lending me both his library of books on color and his time, thoughts, and expertise on color.

My editor at Tarcher/Putnam, Wendy Hubbert.

My team of teachers, Brian Bomeisler, Marka Hitt-Burns, Arlene Cartozian, Dana Crowe, Lizbeth Firmin, Lynda Green-berg, Elyse Klaidman, Suzanne Merritt, Kristin Newton, Linda Jo Russell, and Rachael Theile, who have worked with me at various sites around the nation, for their unfaltering devotion to our efforts. These fine instructors have added greatly to the scope of the work by reaching out to new groups.

I am grateful to The Bingham Trust and to the Austin Foundation for their staunch support of my work.

And finally, my warmest thanks to the hundreds of studentsactually, thousands by nowI have been privileged to know over the years, for making my work so rewarding, both personally and professionally. I hope you go on drawing forever.

Preface

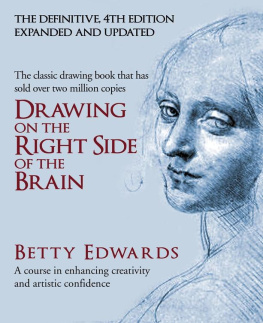

Twenty years have passed since the first publication of Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain in July 1979. Ten years ago, in 1989, I revised the book and published a second edition, bringing it up to date with what I had learned during that decade. Now, in 1999, I am revising the book one more time. This latest revision represents a culmination of my lifelong engrossment in drawing as a quintessentially human activity.

How I came to write this book

Over the years, many people have asked me how I came to write this book. As often happens, it was the result of numerous chance events and seemingly random choices. First, my training and background were in fine artsdrawing and painting, not in art education. This point is important, I think, because I came to teaching with a different set of expectations.

After a modest try at living the artists life, I began giving private lessons in painting and drawing in my studio to help pay the bills. Then, needing a steadier source of income, I returned to UCLA to earn a teaching credential. On completion, I began teaching at Venice High School in Los Angeles. It was a marvelous job. We had a small art department of five teachers and lively, bright, challenging, and difficult students. Art was their favorite subject, it seemed, and our students often swept up many awards in the then-popular citywide art contests.

At Venice High, we tried to reach students in their first year, quickly teach them to draw well, and then train them up, almost like athletes, for the art competitions during their junior and senior years. (I now have serious reservations about student contests, but at the time they provided great motivation and, perhaps because there were so many winners, apparently caused little harm.)

Those five years at Venice High started my puzzlement about drawing. As the newest teacher of the group, I was assigned the job of bringing the students up to speed in drawing. Unlike many art educators who believe that ability to draw well is dependent on inborn talent, I expected that all of the students would learn to draw. I was astonished by how difficult they found drawing, no matter how hard I tried to teach them and they tried to learn.

I would often ask myself, Why is it that these students, who I know are learning other skills, have so much trouble learning to draw something that is right in front of their eyes? I would sometimes quiz them, asking a student who was having difficulty drawing a still-life setup, Can you see in the still-life here on the table that the orange is in front of the vase? Yes, replied the student, I see that. Well, I said, in your drawing, you have the orange and the vase occupying the same space. The student answered, Yes, I know. I didnt know how to draw that. Well, I would say carefully, you look at the still-life and you draw it as you see it. I was looking at it, the student replied. I just didnt know how to draw that. Well, I would say, voice rising, you just look at it... The response would come, I am looking at it, and so on.

Another puzzlement was that students often seemed to get how to draw suddenly rather than acquiring skills gradually. Again, I questioned them: How come you can draw this week when you couldnt draw last week? Often the reply would be, I dont know. Im just seeing things differently. In what way differently? I would ask. I cant sayjust differently. I would pursue the point, urging students to put it into words, without success. Usually students ended by saying, I just cant describe it.

In frustration, I began to observe myself: What was I doing when I was drawing? Some things quickly showed upthat I couldnt talk and draw at the same time, for example, and that I lost track of time while drawing. My puzzlement continued.

One day, on impulse, I asked the students to copy a Picasso drawing upside down. That small experiment, more than anything else I had tried, showed that something very different is going on during the act of drawing. To my surprise, and to the students surprise, the finished drawings were so extremely well done that I asked the class, How come you can draw upside down when you cant draw right-side up? The students responded, Upside down, we didnt know what we were drawing. This was the greatest puzzlement of all and left me simply baffled.

During the following year, 1968, first reports of psychobiologist Roger W. Sperrys research on human brain-hemisphere functions, for which he later received a Nobel Prize, appeared in the press. Reading Sperrys work caused in me something of an Ah-ha! experience. His stunning finding, that the human brain uses two fundamentally different modes of thinking, one verbal, analytic, and sequential and one visual, perceptual, and simultaneous, seemed to cast light on my questions about drawing. The idea that one is shifting to a different-from-usual way of thinking /seeing fitted my own experience of drawing and illuminated my observation of my students.