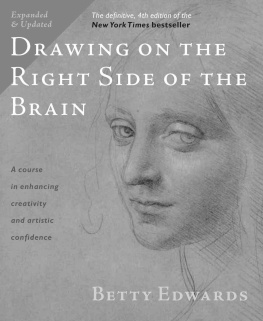

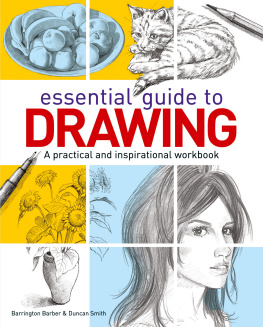

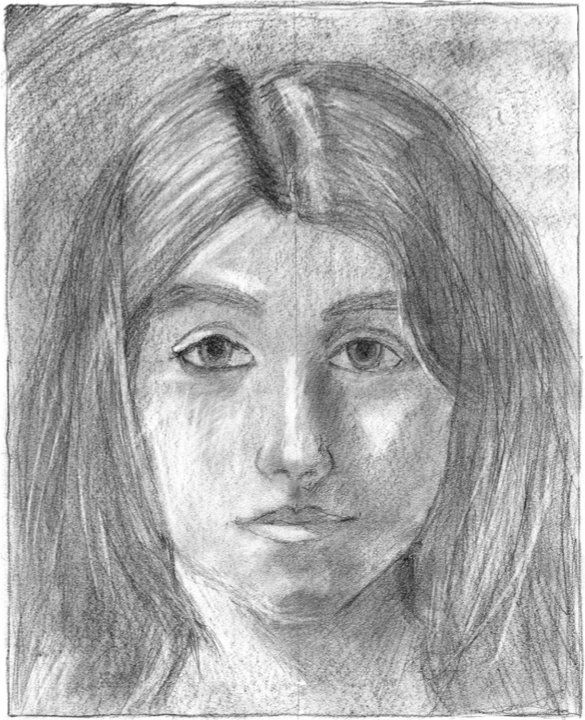

Self-portrait by Sophie Bomeisler, July 29, 2011, when she was 11.

I shall be forever grateful to Dr. Roger W. Sperry (19131994), neuropsychologist, neurobiologist, and Nobel laureate, for his generosity and kindness in discussing the original text with me. At a time in 1978 when I was most discouraged and doubtful about the manuscript I was writing, I summoned the courage to send it to him. Not long after that, I was filled with gratitude to receive his kind response in a letter that began, I have just read your splendid manuscript. He suggested that we meet to review and clarify some errors in my laypersons effort to write about his research. That invitation began a series of once-a-week meetings in his office at the California Institute of Technology, resulting in revision after revision of Chapter Three of the manuscript, the chapter in which I attempted to describe the split-brain studies.

Most gratifyingly, when Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain was finally published in 1979, Dr. Sperry wrote a statement for the back cover:

her application of the brain research findings to drawing conforms well with the available evidence and in many places reinforces and advances the right hemisphere story with new observations.

I asked him why he had used the to begin his statement. He replied, with his usual sly humor, that if any of his colleagues objected to his approval of this nonscientific book, he could always say that something was left out. At that time, objections to Dr. Sperrys findings were frequent, especially regarding his demonstrations that the right-brain hemisphere was capable of fully human, high-level cognition. These objections diminished over the years, as corroboration of his insights became undeniable. The Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1981 ensured Dr. Sperrys eminent position in the history of science.

Many other people have contributed greatly to my book. In this brief acknowledgment, I wish to thank at least a few.

My publisher, Jeremy Tarcher, for his enthusiastic support over more than thirty years.

My representative, Robert B. Barnett of the law firm Williams & Connolly, Washington, DC, for always being a great advocate and friend.

Joel Fotinos, Vice-President and Publisher of Tarcher/Penguin, for setting this project in motion and for his longtime friendship.

Sara Carder, my Tarcher/Penguin Executive Editor, for her enthusiastic support, help, and encouragement.

Dr. J. William Bergquist, for his generous assistance with the first edition of the book and with my doctoral research that preceded it.

Joe Molloy, my longtime friend, who has designed all of my books for publication. Somehow, he makes superb design appear to be effortless, and it isnt.

Anne Bomeisler Farrell, my daughter, who as editor has brought her great writing skills to help me with this project. Throughout, she has been my anchor and support.

Brian Bomeisler, my son, for his long years of work helping me to revise, refine, and clarify these lessons in drawing. His skills as an artist and as our lead workshop teacher have enabled countless students to succeed at drawing.

Sandra Manning, who so ably manages the Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain office and workshops. Her wonderful contribution was in researching and obtaining international permissions to reproduce the many new illustrations found in this edition.

My son-in-law, John Farrell, and my granddaughters Sophie Bomeisler and Francesca Bomeisler, who have been my enthusiastic cheerleaders.

My thanks also go to the many art teachers and artists across the country and in many other parts of the world who have used the ideas in my book to help bring drawing skills to their students.

And last, I wish to express my gratitude to all of the students whom I have been privileged to know over the decades. It was they who enabled me to form the ideas for the original book and who have since guided me in refining the teaching sequences. Most of all, it has been the students who have made my work so personally rewarding. Thank you!

Drawing used to be a civilized thing to do, like reading and writing.

It was taught in elementary schools. It was democratic.

It was a boon to happiness.

M ICHAEL K IMMELMAN

For more than thirty years, Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain has been a work in progress. Since the original publication in 1979, I have revised the book three times, with each revision about a decade apart: the first in 1989, the second, 1999, and now a third, 2012 version. In each revision, my main purpose has been to incorporate instructional improvements that my group of teachers and I had gleaned from continuously teaching drawing over the intervening years, as well as bringing up-to-date ideas and information from education and neuroscience that relate to drawing. As you will see in this new version, much of the original material remains, as it has passed the test of time, while I continue to refine the lessons and clarify instructions. In addition, I make some new points about emergent right-brain significance and the astonishing, relatively new science called neuroplasticity. I make a case for my lifes goal, the possibility that public schools will once again teach drawing, not only as a civilized thing to do and a boon to happiness, but also as perceptual training for improving creative thinking.

The power of perception

Many of my readers have intuitively understood that this book is not only about learning to draw, and it is certainly not about Art with a capital A. The true subject is perception. Yes, the lessons have helped many people attain the basic ability to draw, and that is a main purpose of the book. But the larger underlying purpose was always to bring right hemisphere functions into focus and to teach readers how to see in new ways, with hopes that they would discover how to transfer perceptual skills to thinking and problem solving. In education, this is called transfer of learning, which has always been regarded as difficult to teach, and often teachers, myself included, hope that it will just happen. Transfer of learning, however, is best accomplished by direct teaching, and therefore, in Chapter 11 of this revised edition, I encourage that transfer by including some direct instruction on how perceptual skills, learned through drawing, can be used for thinking and problem solving in other fields.

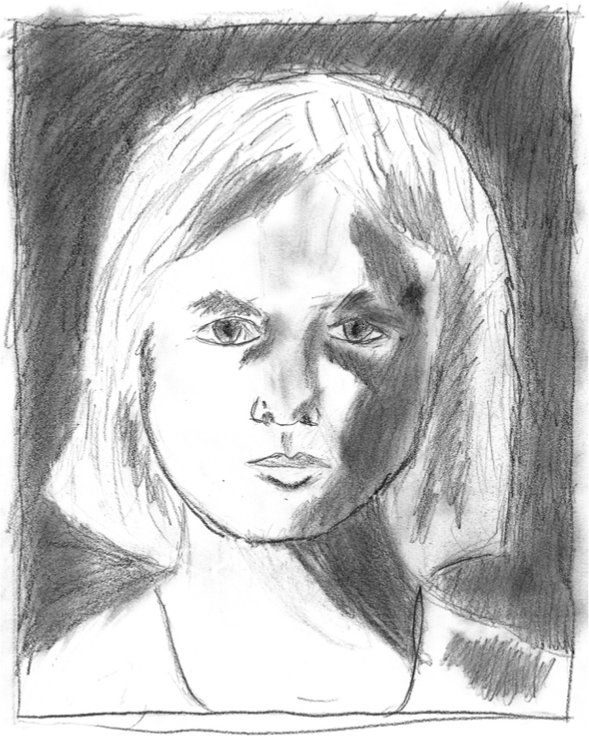

The books drawing exercises are truly on a basic level, intended for a beginner in drawing. The course is designed for persons who cannot draw at all, who feel that they have no talent for drawing, and who believe that they probably can never learn to draw. Over the years, I have said many times that the lessons in this book are not on the level of art, but are rather more like learning how to readmore like the ABCs of reading: learning the alphabet, phonics, syllabification, vocabulary, and so on. And just as learning basic reading is a vitally important goal, because the skills of reading transfer to every other kind of learning, from math and science to philosophy and astronomy, I believe that in time learning to draw will emerge as an equally vital skill, one that provides equally transferrable powers of perception to guide and promote insight into the