AFRICAN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDIES

OF THE 20TH CENTURY

Volume 64

BANTU PROPHETS IN

SOUTH AFRICA

BANTU PROPHETS IN

SOUTH AFRICA

BENGT G. M. SUNDKLER

First published in 1948 by Lutterworth Press and as a second edition in 1961 by Oxford University Press for the International African Institute.

This edition first published in 2018

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1961 International African Institute

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0-8153-8713-8 (Set)

ISBN: 978-0-429-48813-9 (Set) (ebk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-59853-9 (Volume 64) (hbk)

ISBN: 978-0-429-48629-6 (Volume 64) (ebk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

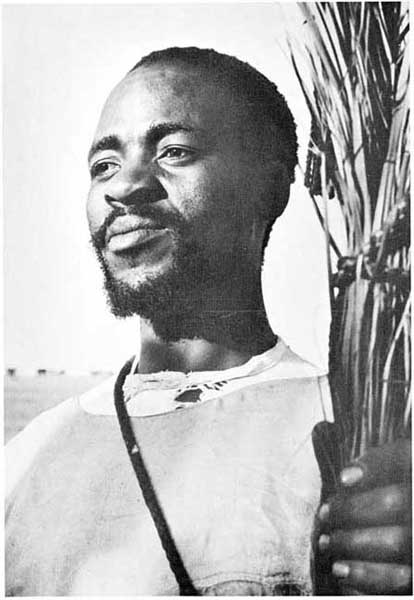

A BANTU JOHN THE BAPTIST.

The white shirt with a green cord have been revealed to the prophet by an Angel in his dreams as a means of overcoming and preventing illness. In his hand a staff of palm leaves.

BANTU PROPHETS IN

SOUTH AFRICA

by

BENGT G. M. SUNDKLER

Second Edition

Published for

THE INTERNATIONAL AFRICAN INSTITUTE

by the

O X F O R D U N I V E R S I T Y P R E S S

L O N D O N N E W Y O R K T O R O N T O

1961

Dr. Sundkler has rendered missionary work in South Africa a signal service by his study of the Bantu separatist churches. It is a subject on which much is known in loose terms, but little with any accuracy. Here we have the facts set out before us in a spirit which is critical in the best sense of the term, objective, and full of a kindly understanding such as the subject undoubtedly merits. There are elements in the life of some of the Bantu separatist churches which are not Christian in any normally accepted sense of the wordthere are elements of true faith and vision. It is doubtful whether any human being can wholly separate the wheat from the tares in this luxuriant field of religious activity, but Dr. Sundkler has done his best.

It is clear from the study which follows that nationalism plays a great part in Bantu separatist church organization and that the spirit of separatism, in spite of quite sincere attempts at union, is very strong. European Christianity in South Africa must face the fact that it is partly responsible for these phenomena. There has been a strong element of nationalism in certain fields of European Christianity and an emphasis on denominational differences which has done harm. It is probable that the very area which Dr. Sundkler surveys so thoroughly is, if one may coin a word, the most over-denominationalized missionary area in Africa. To-day the spirit of comity and co-operation has gone a long way to remove differences between missions. They still exist, but the unedifying competitiveness which was to be found in some areas in the past has been greatly lessened. Europeans none the less must bear their share of the responsibility for a good deal of the separatist church movement and, even when separation has sprung from worldly motives of hurt pride or ambition, it is to be remembered that European missionary superintendents have not infrequently, through an overbearing manner or through lack of understanding and imagination, contributed to secession.

So far I have spoken of separatist churches, but Dr. Sundkler rightly speaks of independent Bantu churches, reminding us that not all the denominations which are studied have their origin in secession from established missionary churches. Not only in independent churches, but also in those which in their origin were separatist, there are elements which spring, not from the faults and defects of European missionary work, but from the desire of the Zulu people to find some synthesis between their own tribal religion and Christianity. Dr. Sundklers researches into this side of the movement are among the most interesting parts of his book.

I should not, of course, like to commit myself to every opinion or conclusion of the author, but I should like to pay tribute, in closing, to the spirit in which he has written; not merely an unbiased scientific spirit, but a spirit which shows true kindness, a positive attitude and a sympathetic understanding of Zulu ideas and aspirations.

E DGAR H. B ROOKES .

This book on Bantu Churches in South Africa first appeared in 1948, and South Africa has changed considerably since then. Yet, when looking at South African society from the standpoint of the particular Bantu religious groups analysed in this study, the change in the political field in 1948 does not appear as sudden or as drastic as it does from the account of other observers. Apartheid, or separate development, as a term may have been coined with the advent of the Nationalist Government; but the fact was of course there long before 1948: the fact of a society divided according to colour lines and of a Church similarly divided. The first edition of this book dealt in fact with church apartheid and its results and consequences prior to 194548. The important event in that development was the Natives Land Act of 1913 : both Separatism as such and the ensuing religious ideology on Bantu lines are an outcome of the deep malaise felt throughout the African masses in the years after 1913.

Thus, when apartheid arrived, the Bantu Separatist Church found itself already apart. Its problems in the 1950s were of course part of those of the African population as a whole, but these problems could, in the world of the Separatist Churches, be approached from the standpoint of apartheid already arrived at, rather than apartheid enforced. In order to understand the post1948 development in the great number of Bantu Separatist Churches, this fact must be borne in mind.

On the invitation of the International African Institute and its Director, Professor Daryll Forde, I had the opportunity of revisiting South Africa for eight months in 1958, with a view to preparing a second edition of this book. My research was once again concentrated on the Separatist Church conditions among the Zulus: on the Rand, in Natal, and in Zululand proper. But there was some widening of the scope of our research. Through the help of Dr. J. F. Holleman, Director of the Institute for Social Research of the University of Natal, I was given the chance of visiting Swaziland. I paid attention to Swazi Zionist and Ethiopian Churches in Swaziland and on the Rand. Here was a cultural and religious situation very similar to that of the Zulusas Northern Nguni they are closely related. Yet there are significant differences in the fundamental factors : land, kingship, political situation.