First published in 1977 by the International African Institute.

This edition first published in 2017

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1977 International African Institute

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-138-23217-4 (Set)

ISBN: 978-1-315-30463-2 (Set) (ebk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-23351-5 (Volume 18) (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-23353-9 (Volume 18) (pbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-30949-1 (Volume 18) (ebk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint butpoints out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

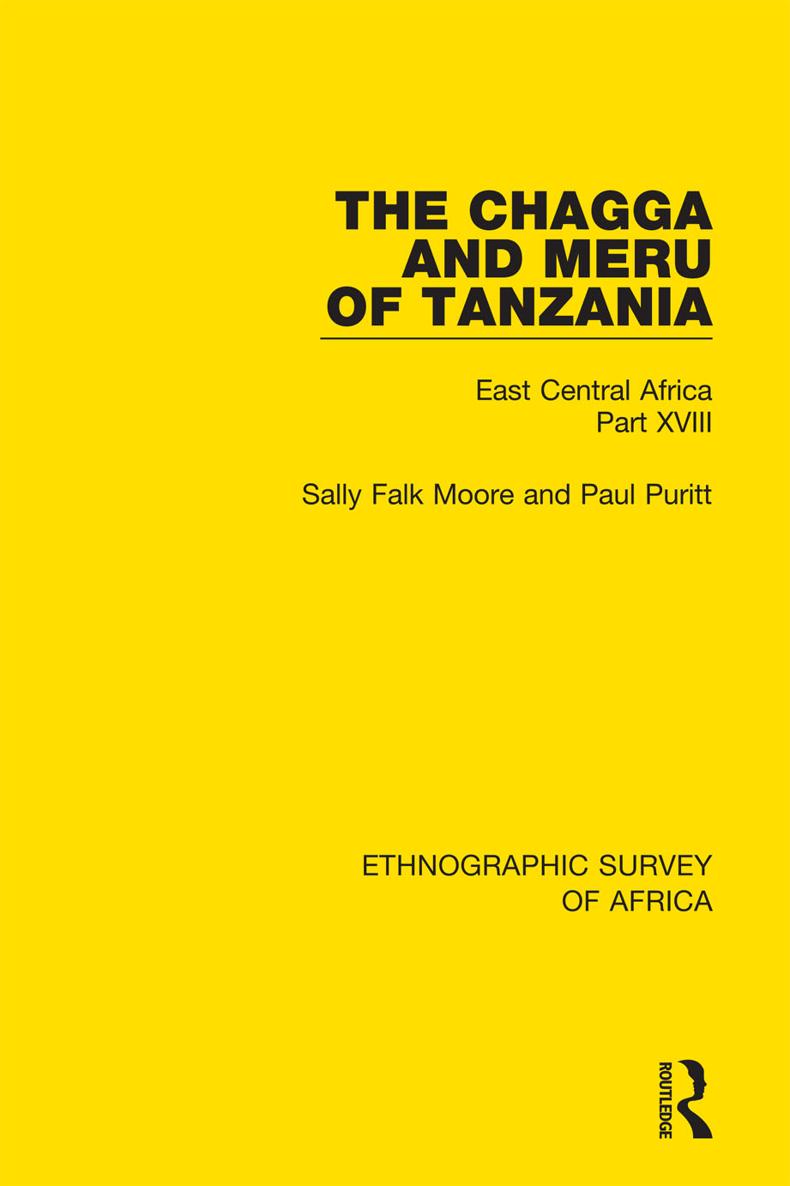

ETHNOGRAPHIC SURVEY OF AFRICA

EAST CENTRAL AFRICA 18

Series Editor: John Middleton

THE CHAGGA AND MERU OF TANZANIA

by

Sally Falk Moore

and

Paul Puritt

Edited with an introduction by

William M. OBarr

INTERNATIONAL AFRICAN INSTITUTE

This volume of the Ethnographic Survey of Africa is intended as the first of two companion parts surveying certain peoples living in adjacent areas of northeastern Tanzania and southeastern Kenya. These peoples and their traditional homelands are: the Chagga of Mt. Kilimanjaro, the Meru of Mt. Meru, the Pare of the Pare Mountains, the Shambaa of the Usambara Mountains, and the Taveta who inhabit a riverine sector of the southeastern plains of Kenya. The present volume is devoted to Meru and Chagga. A second volume, to appear at a later date, will cover Pare, Shambaa, and Taveta.

Four of the peoples Meru, Chagga, Pare and Shambaa consider themselves primarily mountain-folk. They make their livings through hoe cultivation. Hunting, fishing, and the by-products of domesticated cattle provide important dietary supplements. The cultures of these peoples stand in stark contrast to the lifestyle of the non-farming Maasai herders who inhabit much of the adjacent plains. The volcanic origins of Kilimanjaro and Meru make these countries somewhat different geologically from the mountains of Pare and Usambara. Prior to European intrusion, however, all four peoples grew similar food crops, built houses of similar architectural styles, spoke related Bantu languages having mutual intelligibility in some cases, organised and governed their societies along similar dimensions of kinship and authority patterns, and used similar coordinates and categories to conceive of their universe. The Taveta, who inhabit on oasis-like homeland around the Lumi River, share many of their cultural characteristics with the other societies being considered here. Although they are plains-dwellers, their forested country, like the highland homelands of the others, provides a similar contrast with the surrounding arid plains. Taveta are derived from Pare, Shambaa, Chagga, and other neighbouring peoples, and much of their indigenous culture reflects this fact. Thus, they are, in a sense, a lowland, riverine variant of the highland cultures which lie to the west in present-day Tanzania.

When the late Professor Daryll Forde and I first corresponded about the plans for this volume in early 1971, he asked for a regional synthesis of these closely related peoples. Indeed, the many common themes in their traditional economies, social organisations, governments, and cosmologies would provide the basis for an intriguing controlled comparison.1 The vastly uneven nature of the ethnographic coverage of the region posed serious problems. Some of the peoples had been described extensively while others had almost no ethnographic tradition whatsoever. For Chagga, Bruno Gutmanns work alone entailed a 500-item bibliography! In contrast, Ruth Joness Ethnographic Bibliography of Africa published in 1960 listed only four items for Taveta.

The 1960s, however, saw some important changes in ethnographic and historical research in Africa. One of these was a heightened interest in African studies in both Europe and America. Another and in some ways more revolutionary change was the increased involvement of Africans themselves in ethnographic and historical research. This has meant the involvement of researchers like Professor Isaria Kimambo whose work in Pare during the 1960s is now both a well-known and standard text in East African history.2 It has also meant that in some of the more innovative curricula like those in the Departments of History and Sociology at the University of Dar es Salaam pre-baccalaureate students are involved in historical and sociological field research. The paucity of detailed and accurate published materials has been in part responsible for this trend. To learn about African societies and African history, it has been impossible to rely solely upon library sources. But whatever motivations may underly this trend, its impact has been a certain increase in field notes and research materials on African societies and cultures. The richness of the products of these research efforts precludes any simple process whereby this information can be made available to a wider public either in East Africa or elsewhere.

After considering the matter thoroughly, Professor Forde and I agreed upon a plan whereby we would rely upon the skills and knowledge of four researchers each of whom has better first-hand knowledge of the societies which he or she has studied than any single synthesizer could be expected to achieve. We deemed this to be a more efficient manner to prepare and present short, yet comprehensive, overviews of the Chagga, Meru, Pare, and Shambaa. Accordingly, each of the four contributors who are collaborating in producing this volume conducted extensive field research in East Africa during the 1960s and 1970s, and has been a research associate of the University of Dar es Salaam.

When drafts of the first two of four sections were ready, it was apparent that four sections of similar length would be much too long for a single volume of the ESA. Professor Middleton, who has taken over the general editorship of the series after Professor Forde, has kindly arranged to publish the Chagga and Meru sections as the first of a two-part volume on this culture area. A second part containing ethnographic outlines on Shambaa, Pare and Taveta is in preparation for future publication.