Readings from the Lu-Wang School of Neo-Confucianism. Translated, with Introduction, by Philip J. Ivanhoe.

Confucian Moral Self Cultivation, second edition. Philip J. Ivanhoe.

Confucius: Analects, with Selections from Traditional Commentaries. Translated by Edward Slingerland.

Confucius: The Essential Analects, Selected Passages with Traditional Commentary. Translated, with Introduction, by Edward Slingerland.

Mengzi: Mengzi, with Selections from Traditional Commentaries. Translated, with Introduction, by Bryan W. Van Norden.

Mengzi: The Essential Mengzi, Selected Passages with Traditional Commentary. Translated by Bryan W. Van Norden.

Readings in Classical Chinese Philosophy, second edition. Edited by Philip J. Ivanhoe and Bryan W. Van Norden.

Introduction to Classical Chinese Philosophy. Bryan W. Van Norden.

THE FOUR BOOKS

THE BASIC TEACHINGS OF THE

LATER CONFUCIAN TRADITION

THE FOUR BOOKS

THE BASIC TEACHINGS OF THE

LATER CONFUCIAN TRADITION

Translations, with Introduction

and Commentary, by

DANIEL K. GARDNER

Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

Indianapolis/Cambridge

Copyright 2007 by Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

12 11 10 2 3 4 5 6

For further information, please address:

Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

P.O. Box 44937

Indianapolis, IN 46244-0937

www.hackettpublishing.com

Cover design by Abigail Coyle

Text design by Carrie Wagner

Printed at Edwards Brothers, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Si shu. English.

Four books: the basic teachings of the later Confucian tradition / translations, with introduction and commentary, by Daniel K. Gardner.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-87220-826-1 (pbk. : alk.paper)

ISBN 978-0-87220-827-8 (hbk. : alk. paper)

1. Si shu. I. Gardner, Daniel K., 1950- II. Title. Basic teachings

of the later Confucian tradition.

PL2463.Z6S75 2007

181.112--dc22

2006038036

ePub ISBN: 978-1-62466-021-4

To my sister Cindy and her familyBob, Andrew, Madeleine, and Elizabeth

This book is, to a large extent, the product of years of teaching undergraduates about China. In offering courses on later Chinese history and thought, I have found that, although standard textbooks and monographs emphasize the importance of the Confucian canon, and especially of the Four Booksin education, the civil service system, the Confucian orthodoxy, and the maintenance of social normsfew explain in detail what the Four Books taught or how the Chinese of the later imperial period (12001900) studied these texts and assimilated their values. This one-volume introduction to the Four Books is designed, out of some frustration, to fill this gap, and thus indirectly owes much to my students and courses. I have chosen here what I believe to be the most meaningful and interesting passages from each of these texts, translated them, and explained them as they were read by Zhu Xi (11301200), the Song philosopher whose commentaries on these texts provided the standard interpretation of them in China, and indeed, all of East Asia, for the next seven hundred years. The use of interlinear commentary in this study is intended to show the English reader how the Chinese have typically read and understood the Four Books since the Song dynasty (9601279).

Cynthia Brokaw, as ever, has given generously of her time to read drafts of the book and to talk through myriad problems that arose as I worked through the manuscript. She has my heartfelt thanks. She is the sounding board that has made this project betterand far more pleasurable for methan it would have been otherwise. Readers will never know the gratitude they too owe her. I owe a thanks, too, to Marilyn Rhie, a generous colleague of many years, for helping me to select the Shen Zhou painting that graces the cover.

Deborah Wilkes at Hackett Publishing has been the ideal editor. She took an uncommon interest in the project from beginning to end, encouraging me throughout and keeping me to task. Her editorial eye was sharp, her touch gentle. The questions she raised always provoked or clarified.

Finally, Claudia and Jeremy, I am confident that you need never read these acknowledgments to know how much you mean to me.

Fig. 1 A Village School, by Zhang Hong, dated 1649. From James Cahill, The Restless Landscape: Chinese Painting of the Late Ming Period (Berkeley: Chinese Art Museum, 1971).

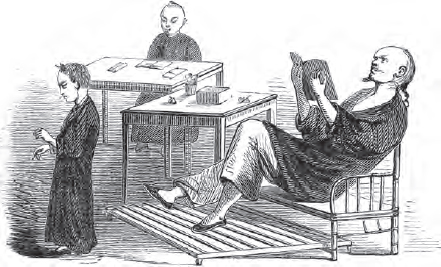

Fig. 2 Backing the Book. From Justus Doolittle, Social Life of the Chinese: With Some Account of Their Religious, Governmental, Educational and Business Customs and Opinions. (New York: Harper & Bros., 1867).

You are a Chinese boy aged seven, born into a family intent on your receiving an education. The year could be any between 1200 and 1900. Your family, if an especially prosperous one, may have engaged a private tutor to teach you at home, perhaps in an elegant study overlooking a tranquil garden with a small pond. More likely, however, your family has but meager resources and has arranged for you to go to the local village school. The school, no larger than a room or two, is dingy and cramped, run by a teacher whose youthful hope of becoming an official has died (Fig. 1). Teaching, for him, is little more than a means of survival. His pay is limited, as is his dedication.

But whether your education takes place in idyllic surroundings with a private tutor or in a squalid schoolroom with a teacher eking out a livelihood, the texts at the center of your studies will be the same: the Four Books. For at least the next eight yearsassuming you continue with your educationyou will devote yourself to learning the Great Learning, the Analects, the Mencius, and Maintaining Perfect Balance. The process will be arduous and not necessarily intellectually challenging or stimulating. Most of your time will be spent in rote memorization, in the exercise of backing the book. You will approach the teachers desk, and with your back to him you will recite aloud, from memory, the line or lines he has asked you to prepare from the book he holds in his hands (Fig. 2). If your recitation is flawless, you will return to your desk and begin work on the next line in the text; forget a word or confuse word order and, with the thwack of a bamboo rod, you will be ordered back to your seat to continue with the memorization efforts. This learning regimen ensures that by the time you are fifteen you will know the Four Books; you will be capable of reciting each of them front to back, line by line, without error.

But your knowledge and capability will go further still. You will be able to recite line by line the extensive interlinear commentary prepared for each by the great Daoxue (lit., school of the Way; commonly translated as Neo-Confucianism) scholar of the Song dynasty, Zhu Xi

(lit., school of the Way; commonly translated as Neo-Confucianism) scholar of the Song dynasty, Zhu Xi  (11301200). It is his commentary that the political and intellectual elite agree best captures the significance of the Four Books, and so it is his commentary that will appear in your editions of the books and will serve as the basis of your understanding of them. When asked by a teacher to explain the meaning of a passage in the Four Books, your explanation will be expected to echo that of Zhu Xi.

(11301200). It is his commentary that the political and intellectual elite agree best captures the significance of the Four Books, and so it is his commentary that will appear in your editions of the books and will serve as the basis of your understanding of them. When asked by a teacher to explain the meaning of a passage in the Four Books, your explanation will be expected to echo that of Zhu Xi.

Next page

(lit., school of the Way; commonly translated as Neo-Confucianism) scholar of the Song dynasty, Zhu Xi

(lit., school of the Way; commonly translated as Neo-Confucianism) scholar of the Song dynasty, Zhu Xi  (11301200). It is his commentary that the political and intellectual elite agree best captures the significance of the Four Books, and so it is his commentary that will appear in your editions of the books and will serve as the basis of your understanding of them. When asked by a teacher to explain the meaning of a passage in the Four Books, your explanation will be expected to echo that of Zhu Xi.

(11301200). It is his commentary that the political and intellectual elite agree best captures the significance of the Four Books, and so it is his commentary that will appear in your editions of the books and will serve as the basis of your understanding of them. When asked by a teacher to explain the meaning of a passage in the Four Books, your explanation will be expected to echo that of Zhu Xi.