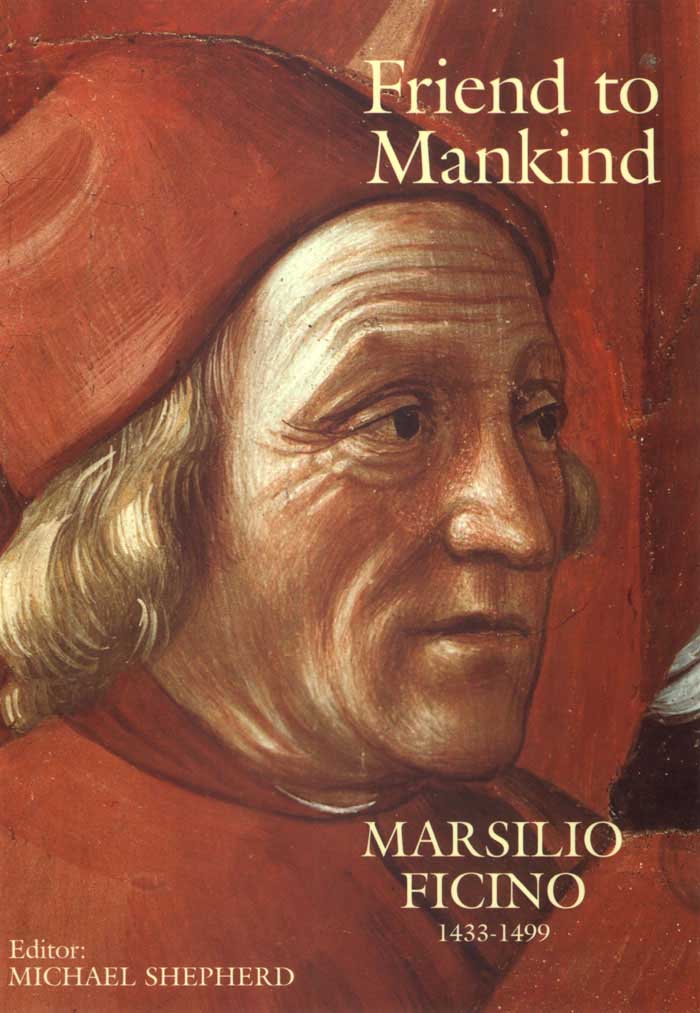

Friend to Mankind

Marsilio Ficino (14331499)

Friend to Mankind

Marsilio Ficino (14331499)

Michael Shepherd

EDITOR

SHEPHEARD-WALWYN

1999 this edition Shepheard-Walwyn (Publishers) Ltd

1999 individual contributors

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the publisher, Shepheard-Walwyn (Publishers) Ltd

First published 1999 by

Shepheard-Walwyn (Publishers) Ltd

107 Parkway House, Sheen Lane

London SW14 8LS

www.shepheard-walwyn.co.uk

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-0-85683-184-3

Typeset by R E Clayton

Printed in Great Britain by St Edmundsbury Press

Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk

Contents

Foreword

S INCE fluency in Latin and Greek has decreased during the 20th century, particularly in the English-speaking world, the very existence of this volume owes a great debt to those who have translated and written about Marsilio Ficino in English: first and foremost, to Paul Oskar Kristeller, who died aged 94 in 1999, and who was the leading authority in bringing Ficino back to the attention of philosophers. Then to Sears Jayne, whose 1944 translation of De Amore revealed the profound influence of Ficinos doctrine of universal love on the arts and literature; to Carol Kaske and John Clarke for their translation of De Vita, Ficinos most intriguing work for contemporary therapeutics; to Michael Allen, for his ongoing translations and researches into every aspect of Ficinos thought, particularly the commentaries on Platos dialogues; and to the team working through Ficinos twelve books of letters, which reveal the inspirational aspect of Ficinos activities.

Gratitude, too, to the memory of Norah Fillingham, whose Christian devotion and inspired elegance of phrase gave wings to the English translation of the letters from the beginning.

Introduction

It is not for small things but for great that God created men, who, knowing the great, are not satisfied with small things. Indeed, it is for the limitless alone that He created men, who are the only beings on earth to have re-discovered their infinite nature and who are not fully satisfied by anything limited however great that thing may be.

T HIS passage, tucked away in a letter to one of his friends, offers the perfect introduction to Marsilio Ficino for those unfamiliar with his writings. It indicates why the 500th anniversary of his lifetime should be cause for celebration; and reason for his rediscovery as one of the great and timeless friends of mankind.

For he is one of those rare beings who seem to be born with the welfare of the whole human race as their prime concern; and he expresses this with love, authority, scholarship, poetic imagination and sublime eloquence.

Re-reading that quotation, we can perhaps begin to imagine difficult historical exercise though this is what it was like for men and women of his own time to hear such inspiring, expansive words for the first time. Their tone is not obviously Judaic, Greek, Roman, Christian or Islamic; yet it harmonises the transcendent teachings of all these traditions, and restates their universal message in a fresh and invigorating way; and with all the authority of personal experience.

It was writings such as this, from his villa at Careggi overlooking Florence and personal contact too, for Ficino delivered sermons as a priest, gave lectures, supervised an academy, wrote letters and is said to have been loved by young and old in his day for his conversation which helped to awaken those surging energies, in many fields of human interest and discovery, which we so marvel at and call the Renaissance.

The last half-century has yielded a considerable scholarly literature concerning Ficino (a guide to further reading will be found at the back of this volume), which has established his historical significance: first as translator of Plato and other philosophers from Greek; as highly influential commentator on these; as harmoniser of classical paganism and Christianity; and whose writings led to the adoption of the belief in the immortality of the soul as Christian dogma; but beyond that, as a voice in his own right, a teacher of mankind, no less.

His influence can be traced in England and in the idealistic New World as much as anywhere through the succeeding centuries, as theologian and philosopher (though himself believing these two terms ultimately to be one), and poetic voice of transcendent love, human and divine; inspiring poets and artists with a new, many-layered language of imagination; and providing the new sciences with psychology literally, the knowledge of the soul.

For those who wish to discover the golden thread of our Western tradition which ultimately must be the tradition of truth itself Ficino is an excellent point of entry. The image which fits him well is that of the hourglass: in the upper cup, the whole of the cultural inheritance of the Mediterranean from Egypt, Israel, Persia and beyond, Greece, Rome, Byzantium and Islam; and from medieval Europe itself. Then at the narrow neck of the hourglass, Ficino himself, filtering and discriminating grain by grain all this word and truth, wisdom and speculation. And in the cup below, the fine tilth of culture which his work provided, a seed-bed for the work of others to come. Following up the authors cited and references in his letters, for instance (the easiest starting point, as he himself intended), can take one deep into this Western tradition and the unimaginable riches of the finest thought and the greatest minds.

This invitation to live a greater life was received with eager enthusiasm throughout Europe even during his lifetime, by kings, prelates, scholars and artists. But what of the present day? Has Marsilio Ficino anything to say to us today worth listening to? Can he still inspire us to believe ourselves greater than our thoughts?

It may come as a surprise to some readers that for a quarter of a century now, in the New World, Ficino has provided an inspiration and method for practising psychotherapists, and a spiritual guide in everyday living; notably in the books of Dr Thomas Moore. It is a merry thought that in America named after the nephew of one of Ficinos friends and correspondents Ficinos name is more widely known than in Europe at this time.

To return to this question of Ficino for today: the answer lies with the reader. Here is a test: on reading that quotation which heads this introduction, is there a warm response whether Thats true or Thats what Id like to believe? If there is that warmth, it suggests two things in particular: that it was written from personal experience, not just from convenient idealist theory; and more, that our response proves that we ourselves already know this greatness, this unbounded nature, within ourselves. It is reminding us of what we are. As Ficino says elsewhere, we are essentially that which is greatest within us which he calls the soul. All his writings are an invitation to all mankind, to live as that greater self; to think and act and love universally, as heirs of the whole Creation; and to find joy in this. His essential message is both profound and practical: the joy, the freedom, of seeking answers to all questions from the viewpoint of the unity of all things. As Ficino himself says, only the unlimited truly satisfies us.