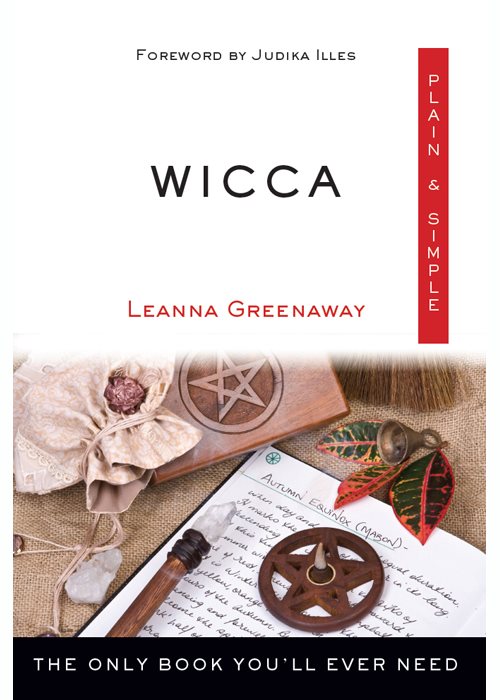

Copyright 2017 by Leanna Greenaway

Foreword Copyright 2017 by Judika Illes

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Hampton Roads Publishing Co., Inc. Reviewers may quote brief passages.

An earlier edition of this book was published as Simply Wicca by Sterling Publishing Co., Inc. New York, 2006 by Leanna Greenaway

Cover design by Jim Warner

Interior design by Kathryn Sky-Peck

Hampton Roads Publishing Company, Inc.

Charlottesville, VA 22906

Distributed by Red Wheel/Weiser, LLC

www.redwheelweiser.com

Sign up for our newsletter and special offers by going to

www.redwheelweiser.com/newsletter/

The author and publisher are not responsible for any adverse effects or consequences resulting from the use of any practices, procedures, or preparations included herein. No responsibility is taken for the use of any herb, and although all of the herbs mentioned are understood to be safe, they should not be taken without consulting your medical professional.

ISBN: 978-1-57174-771-6

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016959343

Printed in Canada

MAR

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

www.redwheelweiser.com

www.redwheelweiser.com/newsletter

Dedication

This book is dedicated to my wonderful husband, Graeme, who came into my life without any knowledge of Wicca and without ever having seen a tarot card. He patiently accepted my witchy way of life and even went on to cast the odd spell himself. He has created my altar, designed my pentagrams, and even polished my wand. Through all of the ups and downs, his support and devotion extended further, to my precious children, who now call him Dad. Taking on a ready-made family, when you have no children of your own, is no easy task, but what a brilliant job he has done so far.

Contents

Foreword

WHILE WRITING MY BOOK, Encyclopedia of Witchcraft, one of my research methods was to simply insert the word witch into every possible search engine I could find, just to see what emerged. I did this with standard search engines, like Google, but also with literally any website that allowed me to search, from eBay to book sellers to museum databases. Using this technique, I discovered all sorts of things about witches and witchcraft that I might not otherwise have learned: some of these things were fun or charming, some were surprising or insightful, and, inevitably, because of the topic, some were tragic.

During one of these searches, I came across an extremely poignant website that had been created to serve as a testimonial and memorial to a Colonial American woman who had been falsely and cynically accused of practicing witchcraft. Like so many others in this situation, she had been convicted and executed. The website was beautifully written by this woman's descendant and I was very moved by it. Her story described how the ancestor had run afoul of a powerful man and the fatal results. This was relevant to my research, as my Encyclopedia of Witchcraft contains an extensive section on the history of witch-hunting. Because this particular website was so deeply personal and touching, I wished to include its link in my own book, so that other readers could experience it, just as I had.

I emailed the site, politely explaining my book project and offering the link to my website, so that she could see my previous publications and that this was a genuine request. Nothing on the site warned me of the response I would receive.

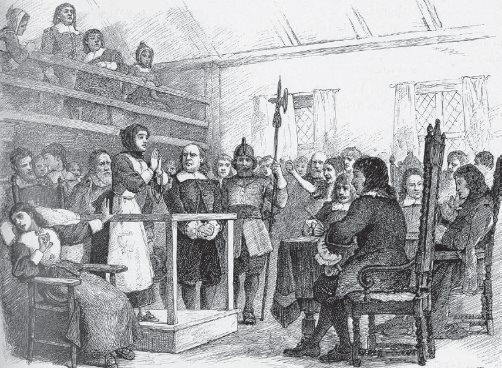

Trial of Martha Corey, illustration by John W. Ehninger, in Giles Corey of the Salem Farms (1868).

That response was immediate. In no uncertain terms, the author expressed her strong desire not to be quoted in my book. She did not want her link included and, furthermore, demanded that the story of her ancestor not be included in the book at all. In her own words, she told me that she did not want her beloved ancestor associated with those awful peopleand by awful people, she meant witches, not their executioners or accusers. Perhaps she meant me.

This occurred in approximately 2005. It was the age of the Internet, not sometime way back in the medieval era or during the dark ages or before the social revolutions of the 1960s. Even today, as I write, although we are in the midst of a metaphysical renaissance, witches still evoke mixed reactions. For every individual like me, who loves and adores witches, who perceives them as heroes, there are others who consider them to be awful... or worse.

Now, you may argue, many of those who perceive witches in a negative light are simply ignorant; they don't understand the witch's true identity. Blinded and deceived by old prejudices and stereotypes, they can't see the inherent beauty of witchcraft: its pride in female empowerment; the way it encourages people to mingle with angels, animal and plant spirits, and the benevolent powers of the universe; and, most especially, the manner in which witchcraft encourages human efforts to harmonize with the elements, the sun, the tides, Mother Earth, and especially the moon; to find our own unique place and power within the cosmos.

There are those who blame this inability to see on etymology. They claim that the word witch itself, with its centuries of negative usage, has become irrevocably tainted. According to this school of thought, if only we could consciously create new ways of expression, then a clear, neutral view of witchcraft might become possible and prejudice would end.

Of course, witch is not the only word to be considered in this fashion. Back when I was a teenager in the 1970s, many words were closely analyzed and reinterpreted. Words, an integral part of the spell-casting process, possess the power to define and to redefine, to guide or control how something is perceived and understood. Thus, during this era, names of ethnic groups, for instance, were consciously tweaked and adjusted. Similarly, during this time, some began to use the word wiccan as a synonym for witch. Witchcraft is a sprawling topic that defies efforts to contain and classify it and so perhaps it's natural that rather than producing clarity, this effort only increased the already-existing confusion.

The word witch may refer to someone of any gender who practices the magical arts. It may refer to a beautiful and thus bewitching woman. Yet some use that same word to shame old women or to brand a woman as difficult or unpleasant. Historically, witch has been used to describe midwives and practitioners of herbal medicine. Nowadays, it may also refer to adherents of Wicca, the Earth-centered religion that celebrates the Wheel of the Year. If someone asks you if you're a witch, it's best to know what they mean by that word before you answer.

Language evolves with time. Beginning in the 1970s, many understood wiccan to be a kinder, gentler, more respectful word for witch. Now, in the 21st century, wiccan more typically refers to practitioners of the religion known as Gardnerian Wicca. Yet the influence of the 70s still lingers and many use the words interchangeably, as does Leanna Greenaway in this book.

Next page