HIGH RELIGION

PRINCETON STUDIES IN

CULTURE/POWER/HISTORY

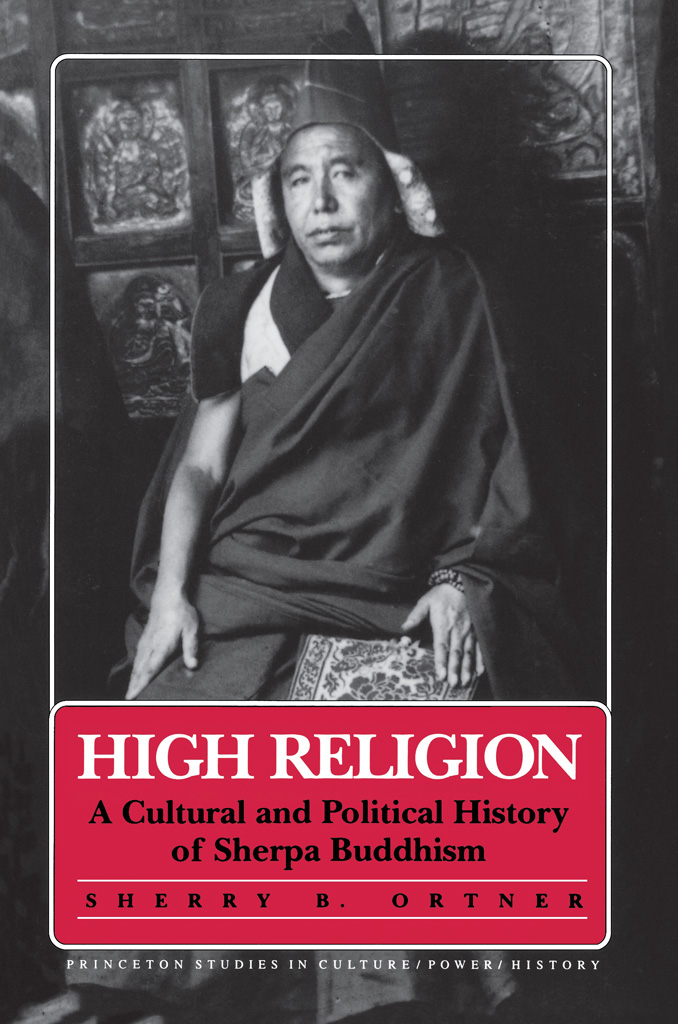

HIGH RELIGION

A Cultural and Political History

of Sherpa Buddhism

SHERRY B. ORTNER

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY

Copyright 1989 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

Chichester, West Sussex

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ortner, Sherry B., 1941

High religion : a cultural and political history of Sherpa

Buddhism / Sherry B. Ortner.

p. cm.(Princeton Studies in culture/power/history) Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

ISBN 0-691-09439-XISBN 0-691-02843-5

eISBN 978-0-691-21807-6

1. SherpasReligion. 2. BuddhismNepal. 3. Sherpas.

I. Title. II. Series.

BL2034.5.S53078 1989

294.3'923'095496dc19

89-30337

CIP

R0

In memory of Nyima Chotar

(19271982)

Nyima Chotar is getting competitive about this project. [He asked rhetorically] Did [a certain anthropologist] photograph a particular set of documents as we did? No. Did [another anthropologist] interview [a certain very knowledgeable informant] at length as we did? No. He is now referring to our book and saying its going to be good.

from the field notes, 1979

Illustrations

.

MAPS

Acknowledgments

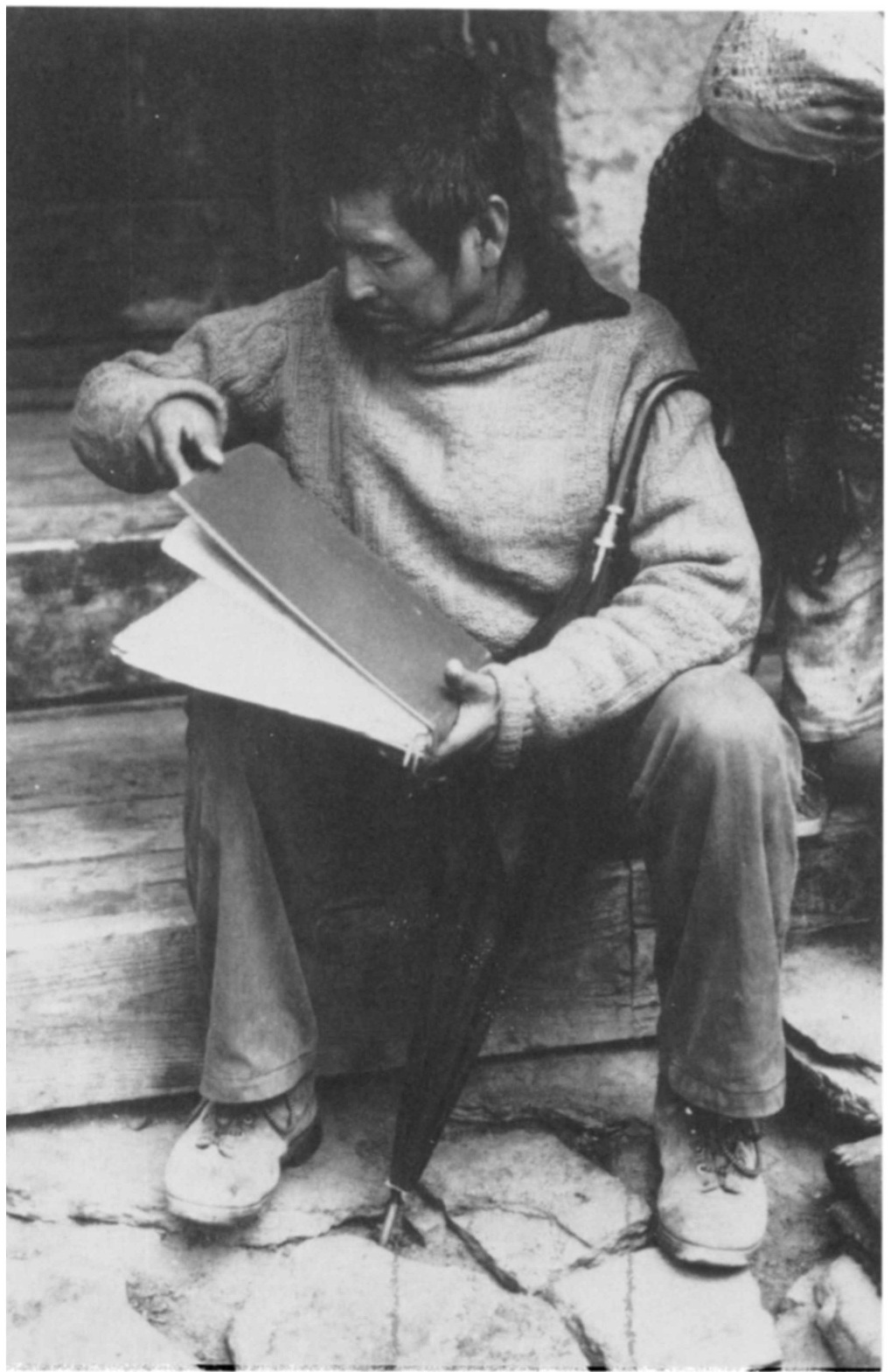

LET me first explain the dedication. Nyima Chotar, of Khumjung, was my field assistant for this project from January to June of 1979. I cannot imagine a more perfect assistant. He was intelligent, responsible, knowledgeable, well-connected, sensitive to the problems of a well-meaning but clumsy anthropologist, and more. He helped me in innumerable ways, includingas indicated in the quote from my field notes on the dedication pageidentifying with the project and making it as much his own as mine.

What was particularly fine about Nyima Chotar, over and above his rock-solid and dignified character, was the fact that although he had worked much of his life for Westernerson mountaineering and scientific expeditionshe was nonetheless utterly at home in his own village context, in which he was an active and highly respected citizen. He managed to use the resources of the world system to the fullest, without any hint of being corrupted by it.

While I was writing the first draft of this book in 198283, I got word that Nyima Chotar and his wife, Sumjok, had been killed along with twenty-six other Sherpas in a bus accident, on the way back from a pilgrimage to see the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala. I am sorry for many, many things about his death, and all the other deaths in that terrible accident, but one thing I particularly regret at this moment is that I cannot send him our book. I dedicate it to him.

Many others in Nepal helped facilitate this project in one way or another. I mention them here in no particular order.

Harka Gurung set up some critical interviews for me in Kathmandu, and also shared with me some good conversations over Star Beer in the rooftop garden of the Crystal Hotel.

Mahesh Chandra Regmi was kind enough to make himself available to me for several useful conversations on Solu-Khumbu taxation, and to provide me with several valuable research leads.

Mingma Tenzing Sherpa and his family provided me with hospitality and friendship in Kathmandu, and worked with me in Khumbu for part of the fieldwork.

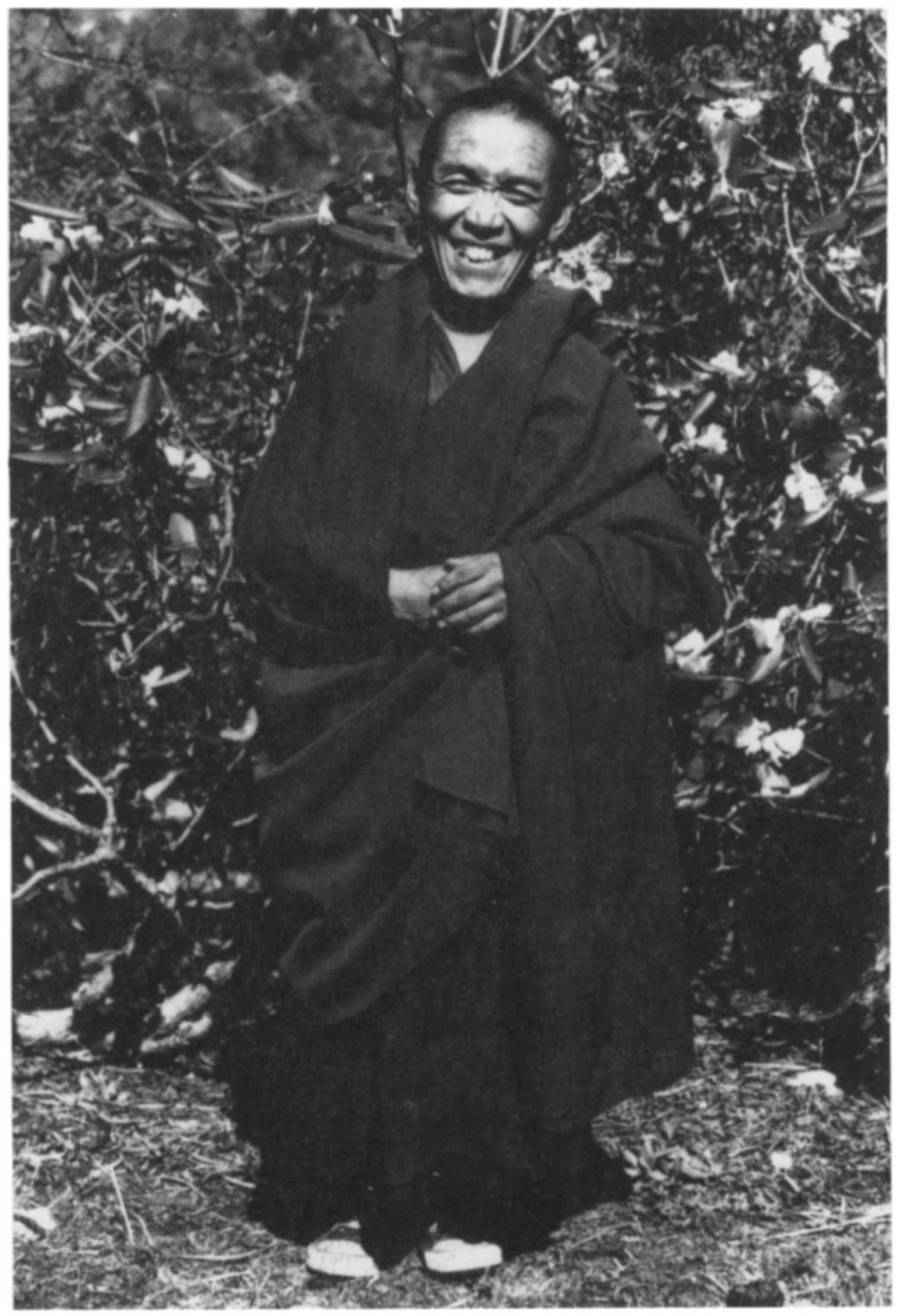

Dawa Namgyal, a Tengboche monk and a relative of Nyima Chotars, was my host at Tengboche monastery for several weeks. He also became my good friend. He is a devoted monk, as well as a person of great warmth and wry humor. He teased me and my anthropologist ways all the time, and I loved it. He also knew many good stories. I especially wish to thank him here for his hospitality and his friendship.

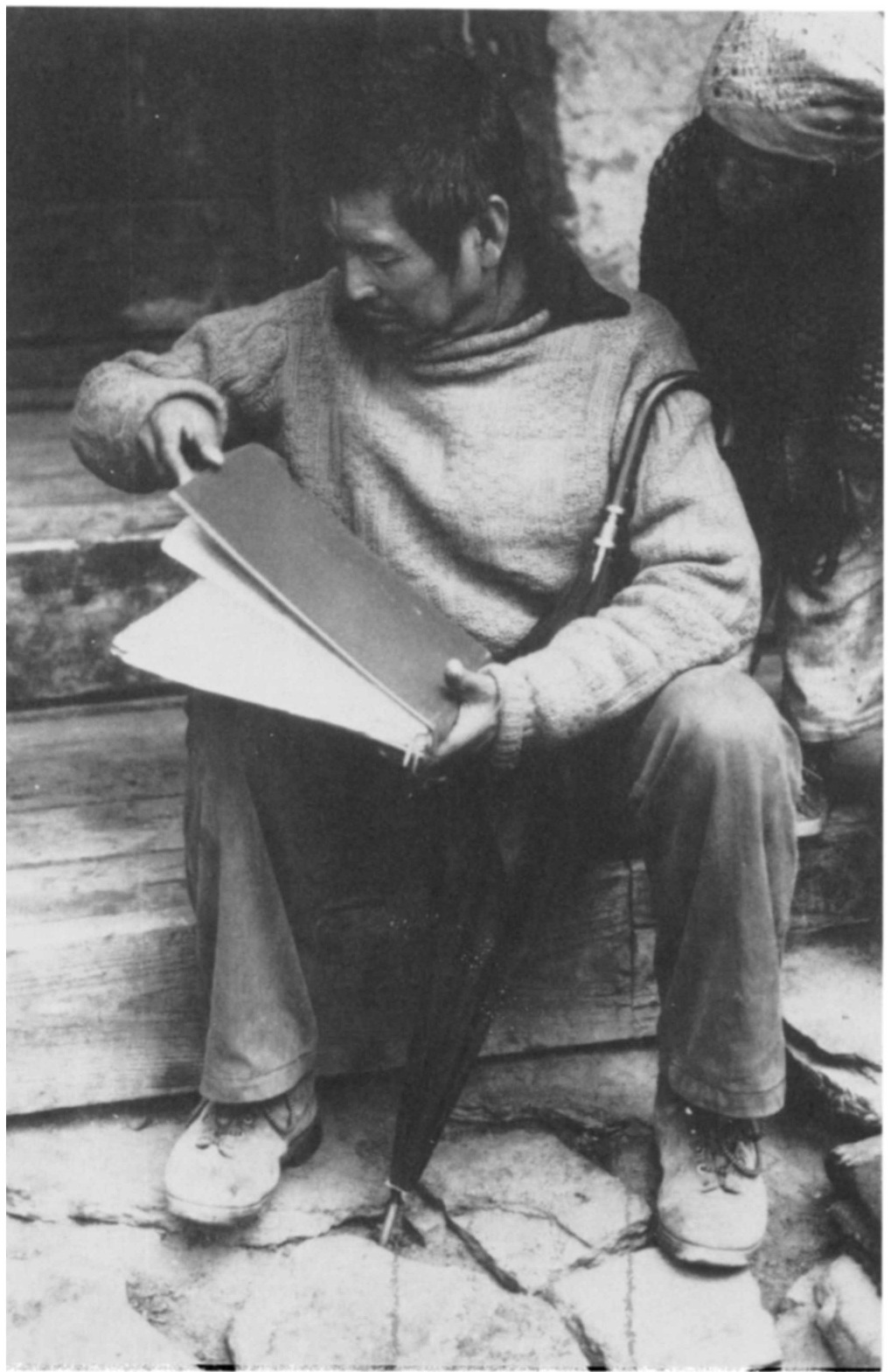

Dawa Namgyal, my host at Tengboche monastery, 1979.

My domestic staff included Nyima Chotars daughter, Ang Teshi, as kitchen girl. Ang Teshi was beautiful and cheerful, a delight to have around. She held my hand in an hour of particular tribulation. The staff also included Mingma Tenzings brother-in-law, Ang Pasang, as cook. Ang Pasang, whom we all called Tsak (Brother-in-law) Pasang, was a wonderful human being, whose special culinary talent was making delicious mo-mo dumplings. His place was taken on the last leg of the trip by Serki, who showed what a professional expedition cook could do.

The Center for Nepal and Asian Studies approved my research project, despite all the rumors I had heard that projects on impractical subjects like religion were having trouble receiving approval. I am acutely aware that I still owe them a final field report, and I hope this book will serve the purpose.

Mike Cheney and the people at Sherpa Cooperative Trekking Ltd. did an excellent job as my agents in Kathmandu, handling much of the dreadful paperwork before I got there, and keeping me well supplied when I was up in the mountains.

The National Science Foundation (Grant No. BNS-7824925) paid for the entire field research, and I am happy to acknowledge their support here. John Yellen, then director of the Anthropology Program at NSF, was particularly helpful and considerate when the grant ran into certain problems later.

For various reasons (including the completion of Ortner and Whitehead [1981]), I was forced to postpone the writing on this project for several years after the fieldwork. It was not until the academic year 198283 that I was finally able to take the field notes out of the closet and begin a first draft of this book, with the support of a Solomon R. Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship and of the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences (National Science Foundation Grant No. BNS-8206304). I am extraordinarily grateful to both the Guggenheim Foundation and the Center for that productive year. I have also subsequently received funding from the University of Michigan Faculty Fund toward the completion of this book.

The manuscript has had many readers. It is impossible to describe the various ways in which each made useful comments. I will simply say that I am blessed with an exceptionally smart and perceptive group of friends and colleagues, who have individually and collectively tried to save me from everything from deep conceptual murkiness to irritating stylistic tics. If they have not succeeded, the fault is entirely my own. Thomas Fricke, Raymond C. Kelly, Joyce Marcus, Harriet Whitehead, and one extremely well informed but anonymous press reader read the entire manuscript thoroughly from beginning to end, and gave detailed, page-by-page criticisms, for which I am deeply grateful. Nicholas Dirks, James Fernandez, Clifford Geertz, David Kertzer, Gananath Obeyesekere, and William H. Sewell, Jr., as well as one other anonymous press reader, plus the students in my Himalayan seminar and the students in Sewells and my seminar on Culture, Practice, and Social Change, all read the manuscript and gave me valuable reactions and insights. There is no doubt whatsoever in my mind that this book would be infinitely poorer without all these contributions.