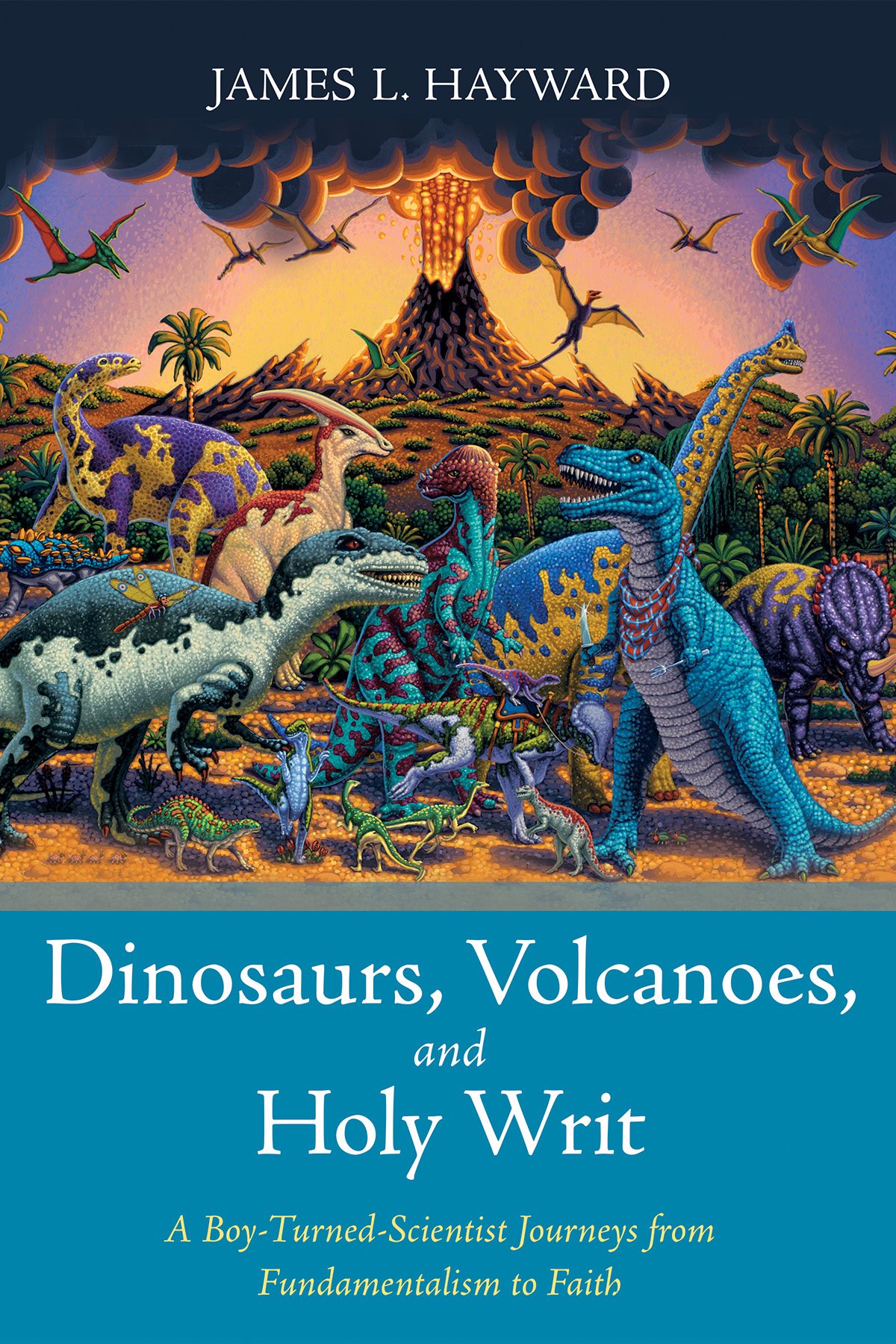

James L. Hayward

Prologue

If the task of the first half of life is to put yourself out there, the task of the second half is to make sense of where youve been.

Susan Cain

A n explosion, deep and rumbling, disrupted the morning peace. Startled, I paused and glanced about. Seeing no danger, I continued measuring the eggs laid by ring-billed and California gulls nesting on this tiny island in an eastern Washington lake.

Two hours later a bank of fierce-looking clouds appeared in the southwest. Last week similar-looking clouds in the southwest spawned a short-lived tornado that roiled fields of wheat and sagebrush. Apparently another storm was brewing.

Except for the explosion and approaching inclement weather, this May morning had been delightfulblue sky, pleasant temperatures, and a slight breeze. By noon, however, the oncoming shroud enveloped the island, making me feel edgy. The gulls appeared nervous as well, oddly swimming about in the eerie calm of the surrounding lake.

By : pm it was too dark to read the scale on the calipers I was using to measure the eggs.

The storm could hit us at any moment, I told Calvin Hill, who had come to help for the weekend. Lets head back to the mainland. We need to be off the island before it hits.

We gathered our gear, hurried to the fiberglass boat awaiting us on the south side of the island, and rowed the quarter mile back to the mainland. As we pulled the boat ashore, we heard crickets singing in the gathering midday darkness. Two fishermen at the landing were packing their tackle.

Looks like quite a storm! I exclaimed, glancing at the angry sky overhead.

You havent heard? Mount St. Helens erupted. This is the ash cloud.

I was stunned. For the past several weeks I had listened to reports about the rumbling volcano, but I never dreamed an eruption would affect us here in eastern Washington. I now understood the source of the earlier explosionand why, at midday, it seemed as if we had entered twilight.

Were part of a geologic event! I exclaimed to Calvin as the strange reality sank in. Lets see how the premature darkness affects the behavior of the gulls!

We had no flashlight or radio, so I drove the six miles back to our rented cabin at the lakes east end to fetch them, while Calvin stayed with the boat. The batteries in the portable radio were dead, so I drove another two miles to the little town of Sprague to purchase replacements.

As I emerged from the variety store, gray dust tickled my nose. I had never experienced a volcanic eruption and naively assumed the dark cloud from a volcano miles away would, like most clouds, simply pass overheadthat would be it. But no, these clouds were collapsing.

Heart pounding, I drove back west toward the boat landing and stirred up ever thickening clouds of volcanic ash dusting the road. I turned down the unpaved lane to the lake. The boat was there but Calvin was not. With mounting anxiety I yanked the boat onto the trailer, jumped into the pickup, and hurried back to the main road.

By now the ashfall was a blizzard with ten-foot or less visibility. The center line was covered with ash and the margins of the road were barely visible. Boat-in-tow, heart-in-throat, I drove back toward the cabin, half expecting a head-on collision.

I barely recognized the turnoff to Sprague Lake Resort at the east end of the lake. Seeing my lights, a wide-eyed Calvin met me as I stopped the truck. He had hitched a ride back in the bed of another pickup and was covered with ash.

This is serious! I exclaimed, my initial excitement now displaced by a deep sense of foreboding. We pulled the boat from the trailer, flipped it over, and took shelter in the old dilapidated cabin.

Complete darkness enveloped us by mid-afternoon. We listened to news reports about damaged engines, ash-burdened roofs, and mounting casualties. Authorities thought the ash might be toxic.

How long would the ash fall? How deep would it get? Was it dangerous to breathe? What would it do to the truck? Would it kill the gulls? Would I need to begin a new project for my PhD dissertation? Was my family okay back in Walla Walla? These and other questions plagued me the rest of the day.

A fter an unexpectedly good nights rest, we awoke to a well-lit, albeit hazy, horizon. The ashfall was over. We wrapped the trucks air filter, loaded the boat onto the trailer, and drove back over an ash-laden road to the landing.

As we rowed toward the island, carp groped for oxygen at the surface. How could any unsheltered organism have survived the suffocating ordeal? Anxious, I braced for the worst.

We landed and made our way up the slope toward the gull colony. An inch and a half of ash, the consistency and hue of dry plaster of Paris, covered the ground. I expected to see dead and dying gulls splayed over the colony surface.

We peered over the crest onto a moon-like terrain. As we did, virtually all the gulls took flight. They were more edgy than usual, but surprisingly there were no casualties. They soon settled back on their territories.

Most of the hundreds of eggs that had been laid were now buried beneath the ash, but a few, mostly those of California gulls, had been excavated by the parents. Many California gulls had black eyesash sticking to fluid oozing from irritated eyes. Curiously, no ring-billed gulls displayed this sign. Perhaps in the process of excavating their eggs California gulls had soiled their eyes.

This day, May , was not only the day after the ashfall, but it also was the first day of hatching. Many of the chicks that hatched survived. A few, however, swallowed ash and choked to death.

Over the first few post-eruption days, more and more nests were excavated from beneath the ash, mostly by California gulls. Although some of the ring-billed gulls followed suit, many members of this species built new nests over the buried nests and laid new sets of eggs.

M ount St. Helens 1980 eruption was a pivotal event for many of us. Although it resulted in a tragic loss of life, both human and nonhuman, it provided scientists with an unprecedented opportunity to study the workings of an active volcano, a study that would help save lives in the future. It also provided an unparalleled chance to monitor and describe ecosystem recovery following such an occurrence.

My concerns about how the ashfall would impact my graduate degree proved groundless. The data I collected transformed a rather mundane dissertation into a fascinating story. I had been keenly interested in both biology and geology since I was a kid. I trained as a biologist, but I always kept an eye open for interesting rocks and fossils. Mount St. Helens afforded a spectacular opportunity to combine my professional interest in birds with my avocational interest in earth science.

Sadly, for some the eruption was a disaster. Luckily for me, it was a serendipitythe people I have met, the places I have visited, and the knowledge I have gained have been remarkable. I developed a more nuanced understanding of earth and life processes. I began to think more deeply about life on earth than was before possible. I was forced to ask questions I might not otherwise have asked.

The eruption occurred during a period of personal reassessment. I had been raised in a loving home by fundamentalist parents. Raised as a fundamentalist believer, yet trained as a scientist to value physical evidence, I had much to think about.