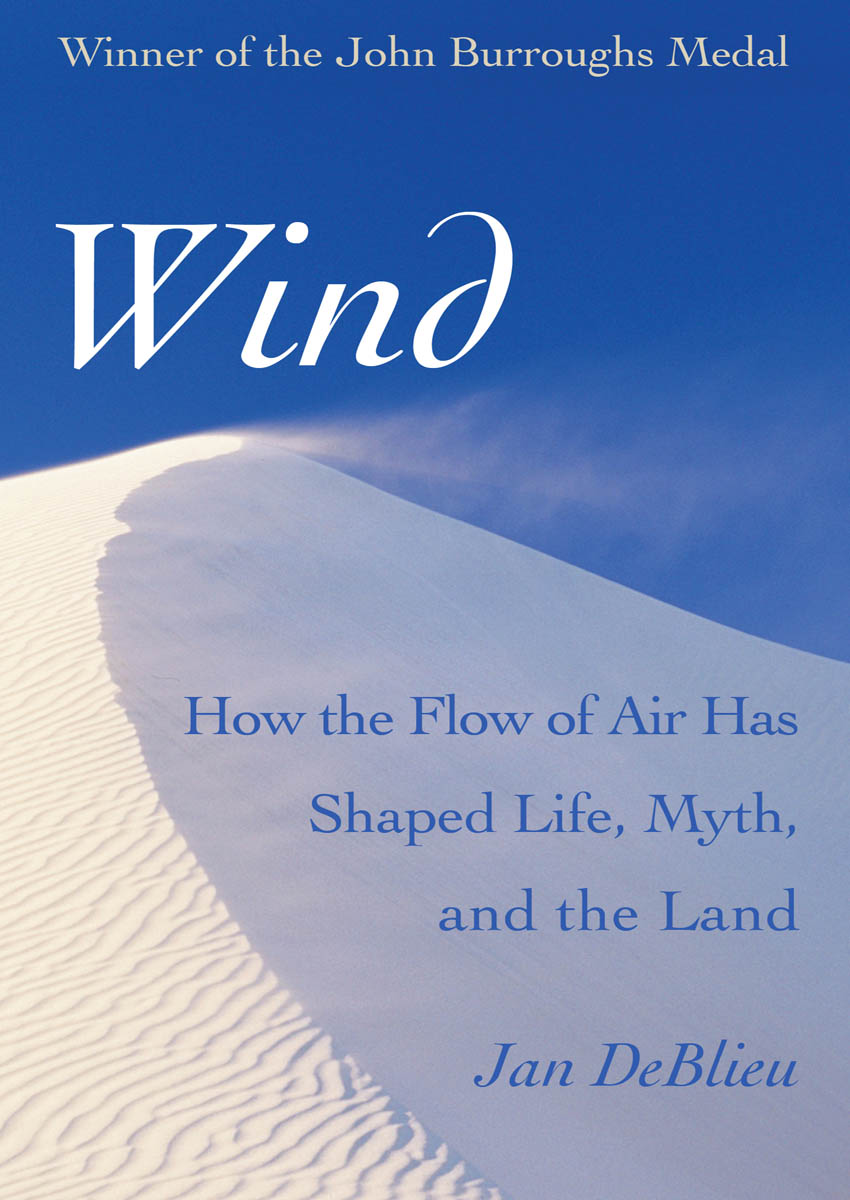

Wind

How the Flow of Air Has Shaped Life, Myth, and the Land

Jan DeBlieu

FOR MOM AND DAD

with gratitude and love

Contents

Acknowledgments

My debts are many and varied. In the course of my research, dozens of people told me of ways in which the wind had touched their lives and the lives of people they know. Without those nuggets, this book would have been much poorer in material and narrower in scope. Thanks to them all.

The scientists named within these pages were all tremendously helpful. Three gave so generously of their time that they deserve special mention: Karen Havholm of the University of Wisconsin at Eau Claire, who is a consummate teacher; Bob Rice of Weather Window in Wolfeboro, New Hampshire; and Steven Vogel of Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. I would also like to thank the staff of the Manteo branch of the Dare County Library, especially Veronica McMurran Brickhouse.

This book would not have been issued in its new, updated format if not for the efforts of Betsy Amster, who found a home for it at Open Road Media. Deep thanks to her and the whole crew at Open Road, who have been accommodating and exacting in the best editorial sense of that word.

The task of writing a book can be as much an emotional journey as an intellectual one. For both their constant support and their nuts-and-bolts assistance with various problems I would like to thank Steve Brumfield, Marcia Lyons, Nancy Cowal, Shay Clanton, Beth and Patrick Martin, Janet Walsh, Sharon LaPalme, Jim Fineman, Maria Merritt, and Stuart Chaitkin.

One warm spring day as we sat on the beach, my husband, Jeff, said rather offhandedly, Why dont you write a book about the wind? With that simple question, he mapped the direction of my life for the next several years. I am indebted to him for the books conception and for the long period of my life that he has served as my mentor. Reid, our son, graciously shared me with the work he knows I love. My parents, Helen and Ivan DeBlieu, offered unflagging love and support. These last four are the pillars of my world; they are my cardinal winds.

No one can tell me,

Nobody knows,

Where the wind comes from

Where the wind goes

A. A. Milne

Come like the wind and cleanse.

Episcopal prayer

ONE

Into the Dragons Mouth

It begins with a subtle stirring caused by sunlight falling on the vapors that swaddle the earth. It is fueled by extremesthe stifling warmth of the tropics, the bitter chill of the poles. Temperature changes set the system in motion: hot air drifts upward and, as it cools, slowly descends. Knots of high and low pressure gather strength or diminish, forming invisible peaks and valleys in the gaseous soup.

Gradually the vapors begin to swirl as if trapped in a simmering cauldron. Air molecules are caught by suction and sent flying. They slide across mountain ridges and begin the steep downward descent toward the barometric lows. As the world spins, it brushes them to one side but does not slow them.

Tumbling together, the particles of air become a huge, unstoppable current. Some of them rake the earth, tousling grasses and trees, slamming into mountains, pounding anything that stands in their way. They are a force unto themselves, a force that shapes the terrestrial and aquatic world. They bring us breath and hardship. They have become the wind.

I stand on a beach near sunset, squinting into the dragons mouth of a gale. The wind pushes tears from the corners of my eyes across my temples. Ocean waves crest and break quickly, rolling onto the beach like tanks, churned to an ugly, frothy blue-brown. The storm is a typical northeaster, most common in spring but also likely to occur in January or June.

Where I live, on North Carolinas Outer Banks, the days are defined by wind. Without it the roar of the surf would fall silent; the ocean would become as languid as a lake. Trees would sprout wherever their seeds happened to fall, cresting the frontal dune, pushing a hundred feet up with spreading crowns. We would go about our lives in a vacuum. That is how it feels in the few moments when the wind dies: ominous, apocalyptic. As if the world has stopped turning.

I lounge on the beach with friends, enjoying a mild afternoon. A light west breeze lulls and then freshens from the east. Its salty tongue is cooling and delightful at first, but as the gusts build to fifteen miles an hour we begin to think of seeking cover. We linger awhilehow long can we hold out, really?until grains of sand sting our cheeks and fly into our mouths. As we climb the dune that separates us from the parking lot, I am struck anew by the squatness of the landscape. Nothing within a half-mile of the ocean grows much higher than the dune line. Nothing can withstand the constant burning inflicted by maritime wind.

On this thread of soil that arches twenty miles east of the mainland, every tree and shrub must be adapted to living in wind laden with salt and ferociously strong. Gusts of fifty miles an hour or more will shatter any limbs that are less pliant than rubber. We have no protection from raw weather here; we are too far out to sea. There is nothing between the coast and the Appalachian Mountains, hundreds of miles inland, to brake the speed of building westerly breezes. There is nothing between the Outer Banks and Africa to dampen the force of easterly blows.

Any book on weather will tell you that winds are caused by the uneven heating of the earth. Pockets of warm and cold air jostle each other, create an airflow, and voil! the wind begins to blow. Air moves from high pressure to low pressure, deflected to the right or the left by the rotation of the earth. It is a simple matter of physics. I try to keep that fact in mind as I stand on the beach, bent beneath the sheer force of air being thrown at me, my hair beating against my eyes. Somehow, out in the elements, the wisdom of science falls a bit short. It is easier to believe that wind is the roaring breath of a serpent who lives just over the horizon.

The wind, the wind. It has nearly as many names as moods: there are siroccos, Santa Anas, foehns, brickfielders, boras, williwaws, chinooks, monsoons. It has, as well, unrivaled power to evoke comfort or suffering, bliss or despair, to bless with fortune, to tear apart empires, to alter lives. Few other forces have so universally shaped the diverse terrains and waters of the earth or the plants and animals scattered through them. Few other phenomena have exerted such profound influence on the history and psyche of humankind.

From the soft stirrings that rustle leaves and grasses on summer afternoons to the biting storms that threaten life and limb, wind touches us all every day of our lives. We pay homage to its presence or absence each time we dress to go outside. We worship it with sighs, curses, and tears. Shes blowin, she is, the captain of a commercial fishing boat told me one stormy day shortly after I moved to the Outer Banks. As I struggled to keep my footing on a salt-slicked dock, I had to agree. Thereafter I made the expression part of our household vernacular. Shes blowin, she is, my husband and I joked those first winters, as Arctic-born breezes set our teeth on edge. She is, she is. But what in Gods name is she?

In strict scientific terms wind is scarcely more than a clockwork made up of gaseous components. The heat of the sun and the rotation of the earth set the system ticking and keep it wound. The gears are simply airs inherent tendency to rise when heated and fall when cooled.

These patterned movements of air fasten into place the bands of wind and calm that girdle our small globe. A belt of constant low pressure rings the earths middle, a weather equator that creates a strip of general breezelessness popularly known as the doldrums. To the north and the south the moist breath of the trade winds stirs the atmospheric stew. The pleasant trade regions are bounded in the northern and southern hemispheres by the comparatively stagnant zones known as the horse latitudesso named, legend holds, because calm air within them slowed the sailing ships of early explorers and forced crew members to conserve water by throwing horses overboard. A significant portion of the worlds deserts lie within the horse latitudes. Above and below 35 degrees, in the two breezy zones that encompass most of North America, Europe, China, Argentina, Chile, and New Zealand, prevailing westerlies revive the flow. These give way to bands of light easterlies that encircle the farthest, coldest reaches of the earth.