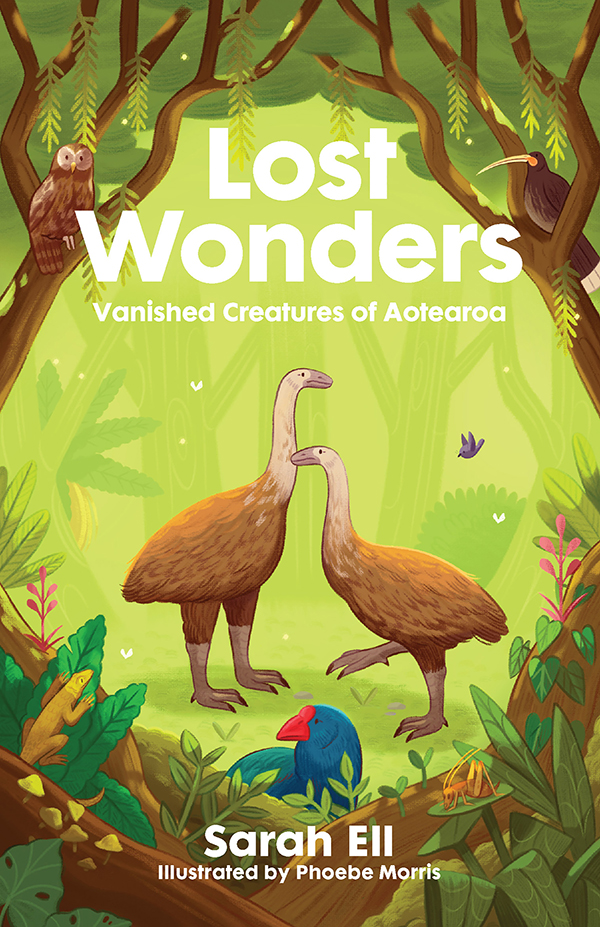

First published in 2020

Text Sarah Ell, 2020

Illustrations Phoebe Morris, 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Allen & Unwin

Level 2, 10 College Hill, Freemans Bay

Auckland 1011, New Zealand

Phone: (64 9) 377 3800

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.co.nz

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065, Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand.

ISBN 978 1 98854 744 2

eISBN 978 1 76087 361 5

Design by Megan van Staden

For my children, Florian and Nataliemay you live in a world where no more of the wonders of Aotearoa are lost

Contents

Imagine that you have travelled back in time to the Aotearoa New Zealand of a thousand years ago. It is a land of vast forests. The three main islands and the hundreds of other small ones around the coastline are almost entirely clothed in rich, verdant plant life, from the subtropical jungles of the north to the gnarled and moss-covered beech and rimu of the south. What we know today as the dry, treeless Canterbury Plains (K Pkihi Whakatekateka a Waitaha) are covered with a thick forest of ttara, kahikatea and matai. Only the tops of the highest mountains and the coldest interior regions of what we now call Central Otago are not cloaked in trees. The North Island (Te Ika-a-Mui) is one gigantic forest, from the seashore all the way into its heart.

This land of forests is also a land of birds. The only mammals present are the seals and sea lions, which loll and roar on the rocky coastline, and the secretive bats, which emerge at dusk to catch insects in flight. In the absence of other animals, hundreds of unique bird species have evolved to fill every ecological niche. Without any furry four-footed predators to fear, many of these birds have become flightless; their wings are stumpy and useless, persisting for show only. The birds are loud and curious. They have never seen a human being and have no fear. They are lords of the forest.

People often say that Aotearoa is a young country, but its roots go further back than we realise. Scientists believe that the islands we live on are just the tips of huge mountains that rise from a much larger undersea continent, Zealandia, 94 per cent of which lies under the Pacific Ocean. This continent, nearly 5 million square kilometres in area, stretches from New Caledonia in the north down to the islands of Aotearoa and beyond, to the south and east, and was once part of the southern supercontinent Gondwana. Zealandia split apart from this landmass about 80 million years ago. As the Tasman Sea opened up, much of Zealandia began to slowly sink below the waves.

Today, however, the islands we know as New Zealand are gradually rising from the sea again. Pressure between the Australian and Pacific tectonic plates (sections of the Earths crust) pushes up the spine of the South Island (Te Waipounamu or Te Waka a Mui) along the Southern Alps / K Tiritiri o te Moana. This is the scientific explanation behind the Mori legend of Mui in his waka dragging up a giant fish from the ocean depths for humans to live on.

What all this geological toing and froing meant for the unique plants and animals of Aotearoa was a complete isolation in which they could evolve. In 1990, British naturalist and television presenter David Bellamy dubbed New Zealand Moas Ark, an apt description for this floating piece of land and its precious cargo. Another description might be a waka huia, a treasure box, containing a cache of wonderful things. Giant parrots which lived on the ground. A huge bird, taller than a human, which reached out its long neck to browse leaves like a giraffe. A nocturnal worm-hunter with nostrils at the end of its beak.

Over time, other species arrived here by accident, blown across the Tasman or out of the Pacific by boisterous winds, but the majority of the species which developed here seem likely to have caught the boat when Zealandia drifted away from Gondwana. Surrounded by thousands of square kilometres of sea, tucked away in the windy southern latitudes far below the populated tropical islands of the Pacific, and on the other side of the world from the centres of Western civilisation, Aotearoa New Zealand slumbered in splendid isolation. It was the last significant landmass in the world to remain undiscovered and uninhabited.

Then, around 800 years ago, the first humans arrived. It could have been just one waka, maybe moreno one knows for sure. But the treasure box had been found and, once found, it was opened. As the Polynesian people settled these islands, they discovered the wondrous birds and life-giving trees, the abundant seafood and the precious materials such as pounamu (greenstone) and mat (obsidian). They utilised the resources they found to survive, taking only what they needed for food, construction, tools and decoration.

Although there were few people living in Aotearoa relative to its sizeeven at the time of Captain James Cooks first expedition in 176970 there were still only around 100,000 Mori living heretheir presence had a fatal impact on the pristine environment. Mori hunted the larger birds for food, skins and feathers, and with human settlement came fire. The deforestation that would see nearly three-quarters of New Zealands native tree cover destroyed forever began as early as the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Large tracts of bush around the eastern coasts and, most notably, the Canterbury Plains were burned off, to make it easier to hunt large prey such as moa and to create land for agriculture. The fires destroyed not only many precious plants but also the habitats of many birds, insects and smaller creatures.

The first Polynesian settlers also brought with them two strange beasts that the birds of Aotearoa had not encountered before: kur, the Polynesian dog, and kiore, the Pacific rat. Jumping ashore as waka grounded on empty beaches, they shook off their wet fur and set out to explore. It was the beginning of the end for many of the wonderful creatures aboard the moas ark.

While nowhere near as destructive as the pest animals the Europeans would later bring, these four-legged predators ran riot in the untouched forests of Tne, killing adult birds and eating their eggs and young. The rats preyed on native frogs and lizards, too. By the time the first organised European settlements were underway in 1840, it is estimated that 6.7 million hectares of forest had been destroyed and at least 30 species of bird had already been hunted, preyed upon and marginalised into oblivion.

Once European settlers arrived, the population of New Zealand grewand it grew fast. As more people began to live here, bringing with them strange animal predators, the death warrants of many more species were effectively signed. In the early 1800s, trading and whale ships started visiting our shores, taking trees and decimating the populations of marine mammals in our waters. Then the Treaty of Waitangi was signed in 1840, and the destruction began in earnest. The people who came to live in the newly declared British colony needed food and shelter. They killed birds to eat, but far greater damage was done by habitat destruction.

The new settlers chopped down forests to build houses and ships, and to clear land to farm animals and grow food. Like the Polynesians before them, they brought pest animals that wreaked havoc on the defenceless birds of the treasure box: rats, larger and more tenacious than the kiore, which could swim and climb; dogs and cats, which hunted for sport; browsing animals like possums and deer; then stoats, ferrets and weasels, introduced to control rabbits but which then ran amok too, and continue to do so. These two things did the damage: the devastation of the forests and the introduction of rapacious pests against which Aotearoas birds had no defences.