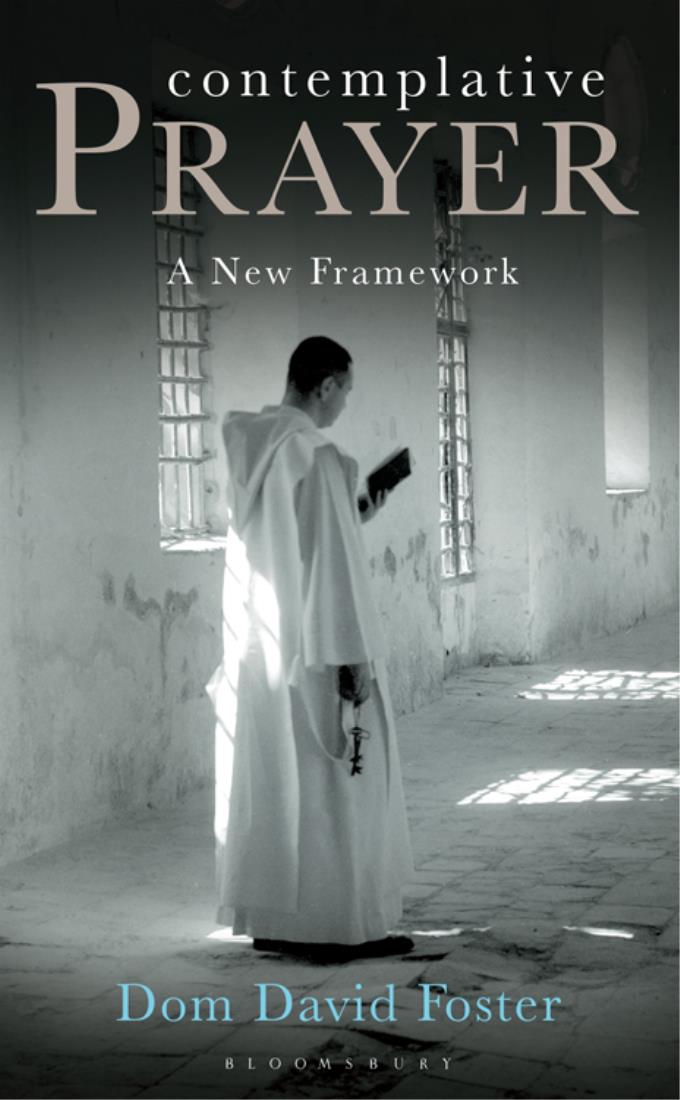

CONTEMPLATIVE

PRAYER

A New Framework

DOM DAVID FOSTER

Wendy Robinson (19342013)

God dropped out of my life one night in Oxford, as I was on my way to visit friends. It was my first term and I was desperately lonely. It was my first time away from home, and I had not faced up to how difficult, how disorientating, it was. And God was not there either. In the bitter cold, a gap yawned. A bit of solid ground I had counted on just crumbled away.

It left me terribly shocked. Explaining it away (as my friends tried to do, and it really was nothing as exceptional as all that) just missed the point. What had gripped me, for the first time, was that I could feel as lonely as that, without God; and, paradoxically, for all his not being there, that I could never have felt so utterly sure of Gods reality the immediacy of absence bore in. It felt like a paralysis of faith. Nothing it had given me to understand up to then bore any relation to the way I found myself that evening as I crossed Parks Road. To re-engage with God became the only thing that mattered.

Paradoxically, I knew I had to pray, and that I had to learn a whole new way of praying, where I could find God in a completely different way. I knew I had to start with that emptiness and let the sense of alienation become less disorientating, to stop still, slowly to find my way around again in the dark. It got me into contemplative prayer, and into monastic life and everything else that has followed. There have been times when it has all made some kind of sense; there have been others too, less startling than the first, back in the difficult terrain where the whole enterprise just seems absurd at best, but where there seems to be no more intelligent choice than to be patient with the sense of estrangement. It is simply, I realize, always as if for the first time. This is what the life of faith is like.

There are practical books on prayer that talk about all this. I want to explore what is involved from a more philosophical point of view. It is the question that I was asking myself back then: how can I be so sure of the immediacy of God when what I am aware of is his absence? Contemplative prayer is how we explore this question. So this book is a philosophical approach to contemplative prayer: what it is and how it is what it is.

The Christian tradition has a great deal to contribute to this, and when I first considered this book I thought it would be enough to reassert the landmarks of this tradition. However, as I began to appreciate the scale of the challenge of modern philosophy to the premises of the earlier tradition, which often focus on Platonism or Descartes, I realized that the philosophical approach I was looking for needed to address a range of fundamental questions. In fact, it would be worth exploring a new approach in order to try to reconnect the tradition of prayer with which I was familiar to more recent philosophy of religion. I was concerned that modern discussions about this tradition were dealing with something different from what I understood as contemplative prayer, but that did not seem to feature much in academic discourse. A telling hiatus. There are plenty of books on Christian mysticism, of course, many dealing with things from a historical point of view; but, as works of spirituality, they did not seem to address the questions I had been asking in trying to make sense of the contemplative dimension of faith.

Dom Illtyd Trethowan, a monk of Downside, used to teach that God was implicit in all our awareness. The problem is to say how. Illtyd argued strongly that our knowledge of God is not a matter of propositional reasoning on the basis of empirical experience, and the psychological categories William James used to talk about Christian mysticism also missed the point because they were essentially just about subjective states. Illtyd believed that recognizing Gods presence was a matter of waking up to what it meant for a human being to be intelligently aware of things, and he was content with a broadly Platonist or Augustinian approach to explaining that.

That is the framework that has, broadly speaking, supported the Christian mystical tradition, and I do not want to reject it in this book. However, I do not think it is as accessible now as it was in the past; for a different starting point, I found myself thinking back to what was going on when prayer seemed actually to be grinding to a halt, when I was aware of almost anything but the presence of God! This made me try to rethink what was going on in the experience of prayer, as it were, without bringing God into it. The idea was, therefore, to try to think through how God does come into experience, when, of course, there is nothing in empirical terms to show for it.

The paradoxical idea of leaving God out of the experience of prayer is the kind of bracketing that is characteristic of Husserls method in phenomenology. It means trying to describe experience from the subjects point of view (as a phenomenon), without any preconceptions about how whatever it might be can be the object of a persons experience. The phenomenologists concern for experience, then, is not for its subjectivity in a psychological sense, but for the way reality engages us, recognizing too that it does so in more than just cognitive or propositional terms, but through our whole way of being in the world.

Contemplative prayer is concerned with God as, in some way, the ultimate reality or, in some way, at realitys heart. And there are plenty of explanations about that, on both sides of the question whether or not he even exists. It is striking how a person who prays can somehow remain undisturbed by all the argument; even if the questions are live ones, prayer somehow works in a different way, on a different level. It engages with reality whatever its explanation in a different way. What it engages with, together with how that manifests itself to a person in prayer, is strange and sometimes deeply disturbing; it is also a source of fascination, sometimes of pleasure and delight. From the phenomenological point of view, it is complicated by the way the faith of the person who prays conditions the subjectivity that engages in experience, and, obviously, by the way in which the account is trying to describe a reality that is known by contrast with everything else.

This is an additional reason for my interest in the modern sense of disorientation, of loss, including the loss of meaning and of purpose of being left hanging in the air (and in the dark): they can be places where people discover a call to prayer, whether or not they have the rooting in Christian practice to help them make sense of it in those terms. Some of these concerns are also represented by various styles of nihilism. I found nihilism spoke to my own sense of hollowness as well as pointing rather well at the hollowness it is possible to feel about religion. But this experience of doubt and bewilderment has a potentially religious value as a call to human growth. This bewildering place is a place of prayer. Contemplative prayer can be a way into faith; it is certainly how it grows, and how it teaches us to live forwards into hope.

The approach I outline in this book is an attempt to describe, in the experience of prayer, how God comes in. As such it has a phenomenological side to it. But I also try to reflect on the philosophical implications of that kind of account. The phenomenological side of the discussion focuses on the paradoxical experience of being drawn into something that seems empty, where we find ourselves addressed, but by a blank that, nevertheless, seems to be the essential and ultimate thing. Trying to understand that philosophically raises metaphysical and epistemological questions. Ultimately I try to bring together what I call a traditional approach and one I describe in relation to the concerns of more recent philosophical work. Although I am not convinced by the more sceptical forms of postmodernism, its critique of modernity opens up a field where the earlier traditions of Christian thought and experience can be explored in new ways. This book cannot do much more than dip the toe in these rather deep waters, but I hope it will help the reader towards an understanding of what contemplative prayer involves and of its deep roots in human intelligence and human being.

Next page