Published in 2020 by The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2020 by The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

First Edition

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hessel-Mial, Michael, author.

Title: How STEM built the Incan empire / Michael Hessel-Mial. Description: First edition. | New York: Rosen Publishing, 2020. | Series: How STEM built empires | Audience: Grades: 712. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019013256| ISBN 9781725341470 (library bound) | ISBN 9781725341463 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: SciencePeruHistoryJuvenile literature. | TechnologyPeruHistoryJuvenile literature. | EngineeringPeruHistoryJuvenile literature. | MathematicsPeruHistoryJuvenile literature. | Incas MathematicsJuvenile literature. | IncasHistory Juvenile literature.

Classification: LCC Q127.P4 H47 2020 | DDC

509.85/09024dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019013256

Manufactured in the United States of America

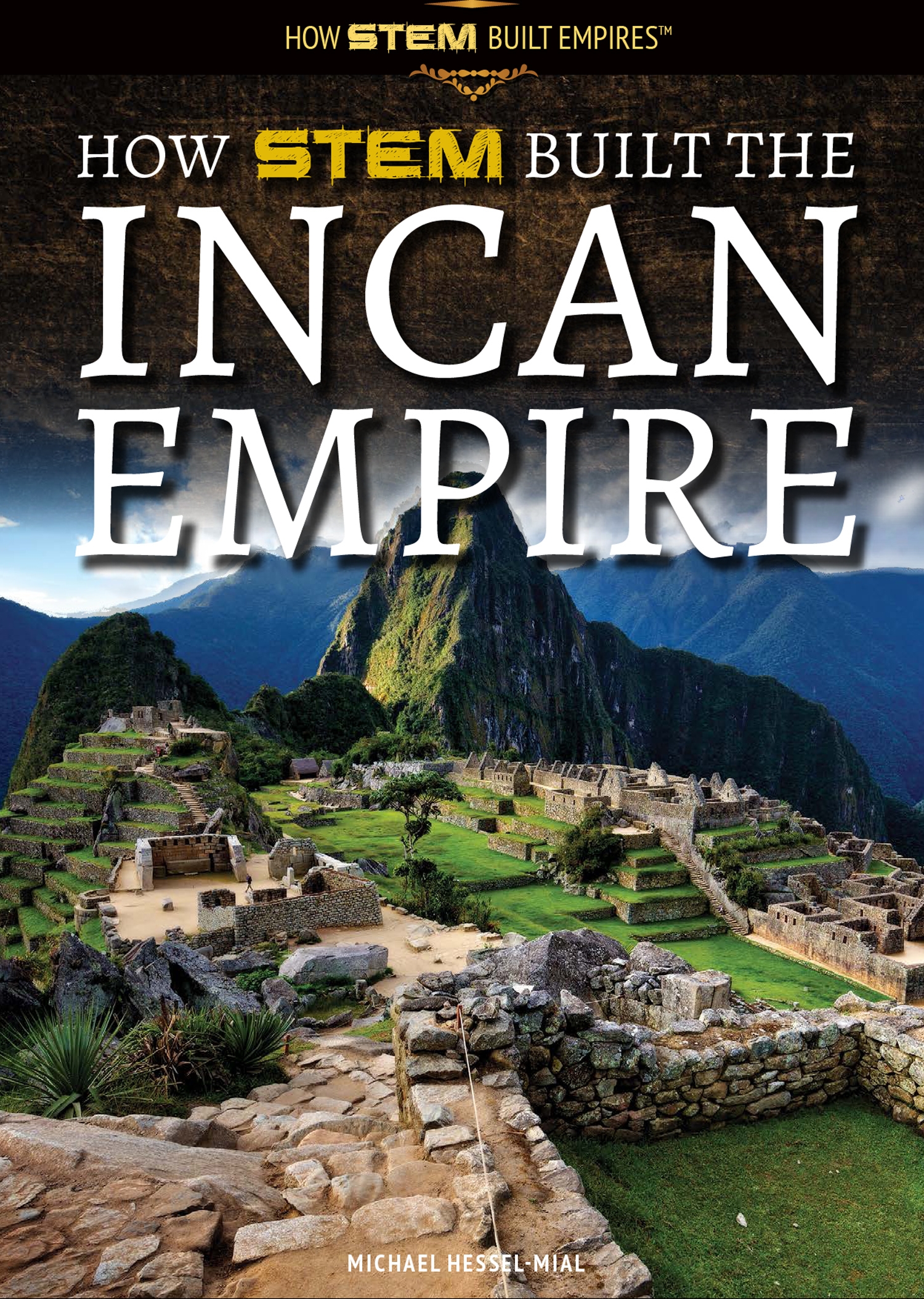

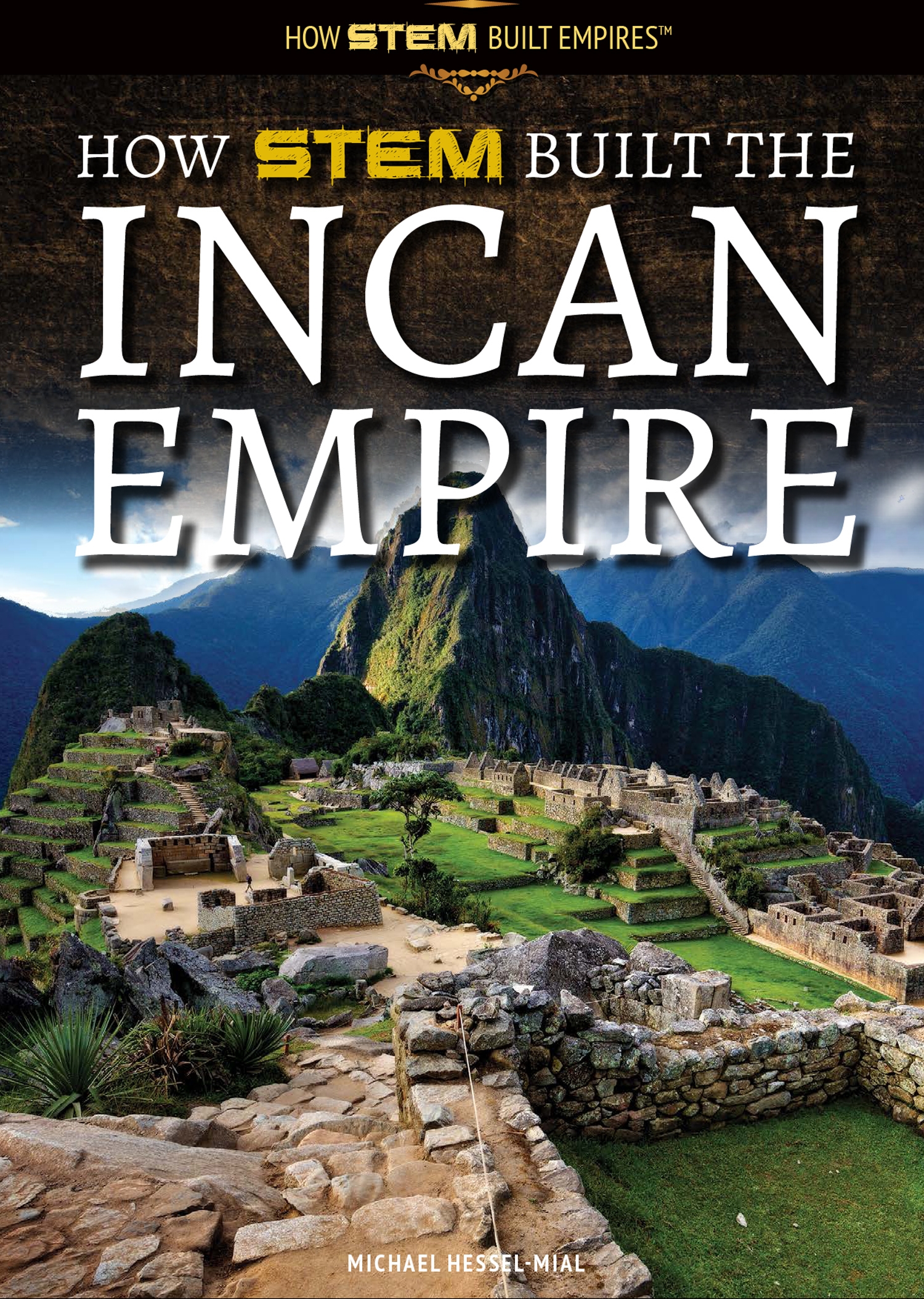

On the cover: Incan ruins like these are among the longestlasting and most impressive structures in the Americas.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

T o anyone who has studied world civilizations, a few features of organized society consistently stand out as essential. The wheel is one such important invention. Likewise, it is impossible to imagine a major power without some form of writing for communication. Digging deeper, one might identify a favorable climate, metal tools, or useful pack animals to help people carry things as other essential elements. It is hard to build any civilizationlet alone a great onewithout these features.

The civilization of the Incas, founded at an undefined date in the thirteenth century, is a significant break in assumptions about most civilizations. This sophisticated society used no wheels or iron; had no friendly climate for growing or travel; and had no writing system resembling those used in other great societies. Yet these mountaindwelling people built an empire that was the most powerful in South America at the time of European exploration. Spanning the Andes mountain range over thousands of miles, the Incan Empire absorbed smaller cultures in climates ranging from mountain to rain forest to desert, spreading its unique technologies along the way.

The Incas adapted to their environment with remarkable inventions, some borrowed and some homegrown, and used them to administer the needs of a mighty state. Struggling to farm the slopes of the mountains of the Andes, the Incas rebuilt the landscape with terrace architecture. They used common-sense hand tools to shape the stones into earthquake-proof buildings and roads. They took advantage of geographic diversity to cultivate and trade a wide variety of crops. They used textiles to produce a form of communication seen nowhere else in the world: the quipu, a system of knotted yarn that conveyed mathematical datait is still being interpreted by scholars today. By looking at the Incan Empire, it is obvious that the science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) innovations that civilizations deploy are often shaped by their unique worldview and circumstances.

This painting of Manco Capac, legendary founder of the Incan Empire, depicts traditional Incan symbols in a European style.

The Incan Empire created a set of ideas for how society should be ordered, which gave direction and purpose to the STEM its people utilized. Like the Roman Empirewhich wanted to spread its unique legal code around the Mediterranean worldthe Incas had a complex governing system that linked religion, social order, and the economy. Centered around the sacred capital of Cuzco, every geographic region was given a distinct economic and religious role. As the empire expanded, conquered groups were absorbed into the system, preserving their religious beliefs while accepting the power of Inti, the Incan sun god. In exchange, Incan society took responsibility for caring for each individual in times of need, creating a moneyless society organized with information from the quipu.

Incan civilization, like many other complex societies in the Americas, was conquered and destroyed by European explorers in the sixteenth century. As a result of this destruction, scholars in modern times are left with the task of reconstructing this civilization. By sifting through archaeological data, decoding quipus, poring over Spanish chronicles of the Incas, and speaking with Incan descendants still living the old traditions, it is possible to interpret how STEM built the complex Incan world.

CHAPTER ONE

THE SON OF THE SUN CREATES AN EMPIRE IN CUZCO

W ell before the Incas became an empire, the Andean civilizations were distinctive, developing their unique technologies without any influence of societies outside the region. Around 1400 BCE, in the period historians call the Early Horizon, Chavn civilization created religious traditions and weaving techniques that influenced the later Moche and Nazca cultures. During the Middle Horizon period (6001000 CE), the Tiwanaku and Huari established small, influential empires. The Tiwanaku ruled near Lake Titicaca and developed stone masonry imitated by the later Incas. The Huari ruled further north, building roads and inventing the quipu. Both of these societies mysteriously disappeared and were replaced by fragmented warring states. Scholars are especially curious about these societies influence on the Incasthe Quechua-speaking valley-dwellers who began expanding from their center in Cuzco in the twelfth century CE.

INCAN ORIGINS: MYTH AND REALITY

Incan legends say that the god Viracochason of the sun god Inticreated the Tiwanaku from stone.

Shown here is a statue of Pachacuti, the ninth Sapa Inca. Pachacuti is traditionally credited with major land conquests, the design of Cuzco, and the composition of many Incan hymns.

A male-female pair, Manco Capac and Mama Ocllo, were specially chosen from the Tiwanaku to bring the sun cult to the small village of Cuzco. Manco Capac was the Sapa Inca, the name for Incan rulers, and considered the common ancestor of the empire.

Manco Capacs heirs are said to have invented terrace agriculture and the mita system, which was a tax paid in labor rather than money. It was Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui, an emperor whose name meant earth shaker, who turned the growing Incan state into a full empire at the end of the fifteenth century. He is credited with inventing the empires core institutions, including the Inti sun cult and ritual calendar, the urban planning of Cuzco, and ritual poems and dances commemorating Incan power.

Of these founding myths, passed along by Spanish chroniclers, only some are true. Pachacuti was indeed a military ruler who helped shape Incan identity and institutions when he took power in 1438. However, the historical early expansion was considerably milder than these myths suggest; the surrounding Colla, Wanka, and Chanca cultures were tiny villages that were absorbed due to Cuzcos growth as an economic power. While surrounding states focused on war, building defensive settlements from 1000 to 1400, the early Incas invested in centrally organizing agricultural production. Expanding output with irrigation and terrace agriculture, the early Incas urbanized and absorbed these smaller neighbors.

Next page