I recall the New Forest in childhood and explored it in the 1950s. It has been my home and I have been involved in its affairs since 1960 when almost by accident I found myself working in the Nature Conservancy (since 1974 the NCC). The Forest has not been my only professional concern or research interest since then, but it has been of constant and absorbing interest. The absorption grows with time partly because over long time spans, it becomes possible to measure and witness changes which illuminate the relationships between soils, vegetation, animals and management in ways which no short-term study can achieve; and partly because time increases rather than diminishes the degree of spiritual renewal and intellectual wonder to be derived from the familiar woods and heaths.

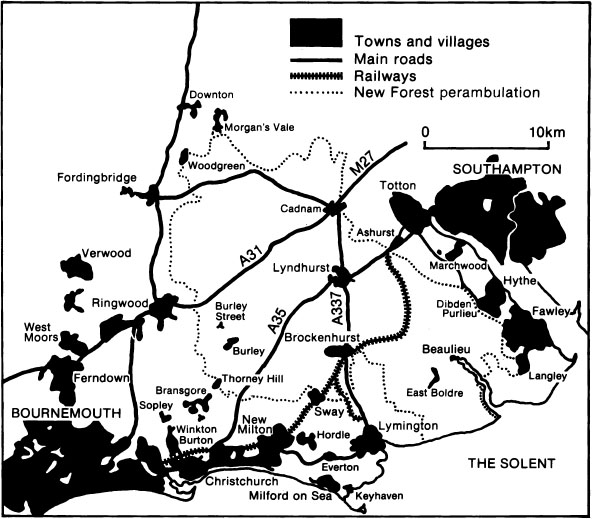

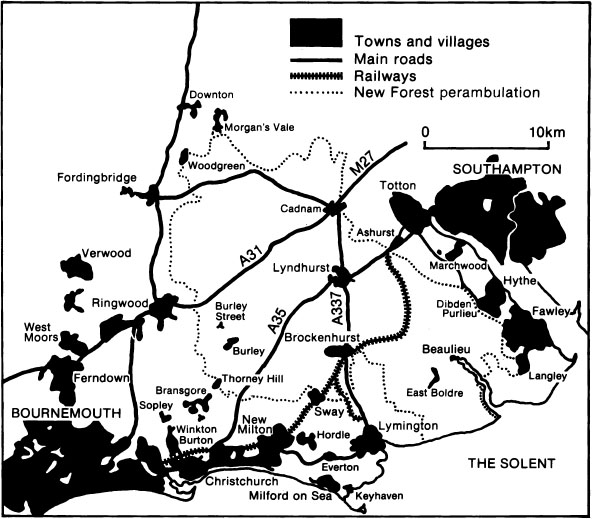

Seen obliquely from the air, the Forest is a series of eroded flat terraces, highest in the north, lowest in the south. The middle terraces are scoured into wide hollows drained by two south-flowing stream systems which empty into the solent. The terrace surfaces are mostly mantled in heathland and the hollows and valleys between them are a mosaic of woodland, heath, grassland and mire. Superimposed are the mainly regular blocks of Silvicultural Inclosures dating from the early 18th century onwards, and the more rounded enclaves of farmland and settlements.

The New Forest is an ecological system which is constantly developing under the influence of large, free-ranging herbivores mainly deer, domestic cattle, and ponies. The exercise of common rights (by which stock are depastured on the unenclosed forest) is as intimate a part of the ecosystem as the vegetation. The botanical composition of the Forest and the morphology of many individual species are much modified by grazing and browsing. At the same time, the inherently low productivity of the poor, acid Forest soils, combined with the effects of intensive grazing, influences both the productivity (in terms of live weight gains and young produced) and behaviour of the animals.

The unenclosed Forest is the largest area of wild, or unsown vegetation in lowland Britain and includes large tracts of three formerly common habitats that are now fragmented and rare in lowland western Europe heathland, valley mire and ancient pasture woodland. Nowhere else do these habitats now occur on so large a scale and nowhere else do they occur in such an intimate mosaic. There are nearly 20,000 ha of unenclosed Forest. Nearly 3700 ha of this is mainly oak, beech and holly woodland much of it on sites which can probably claim an unbroken history of woodland cover for 5000 years or more. There are nearly 12,500 ha of heathland and acid grassland; and 2900 ha of valley, seepage step mire, and wet heath. There are also 837 ha of plantations, of which about 40% are broadleaved, including large tracts of fine 18th- and 19th-century oakwoods. The woods, heaths and mires are drained by many small streams which, though locally modified by canalisation, remain of great interest for their little-disturbed communities of aquatic plants and animals.

The scale of the Forest heaths, mires and pasture woods is such that they offer the best chance of survival to the widest possible spectrum of their characteristic flora and fauna. Many of the species found would seem unable to persist on smaller fragments of habitat. The three main habitat formations of the unenclosed Forest are intrinsically rich in species, relatively undisturbed, and managed and used in such a way as to ensure their survival. A key element is the persistence of a pastoral economy based on the exercise of common rights of grazing and mast (the right to turn out pigs in the autumn). This inhibits a succession to uniform woodland and gives rise to great local variation in plant communities. The pastoral use of the Forest depends on the continued existence of a close-knit human community of mainly part-time farmers and smallholders. Most comparable communities and the attendant grazing of commons, have disappeared from the lowlands of western Europe. The Forest survives as an ecological system of interacting natural and social elements which now has no parallel, at least in scale.

The perambulation of the Forest encloses 37,907 ha. In medieval times the perambulation was the limit of the area within which the forest law had jurisdiction. Today its main significance is that it delimits the area within which the New Forest Verderers apply their by-laws for the control and health of the stock depastured on the commons, and within which the animals are contained by road grids and, where necessary, fencing. Nearly a quarter of the area within the perambulation consists of farmland and settlements, among which the animals forage only on lane sides and greens. A further 1399 ha are composed of the unenclosed wastes of various manors that border the crown lands, and are indistinguishable on the ground from the unenclosed Forest proper. Most of these are owned by the National Trust, but a large and important group on the western edge of the Forest is within the Somerley Estate and there are a number of other, smaller areas in private ownership. The National Trusts Bramshaw Commons, detached from the main area of the Forest by the enclosed lands of Bramshaw and the Warrens Estate, have always tended to maintain a separate identity and life of their own, and have an active management committee on which interests besides those of the commoners are represented.

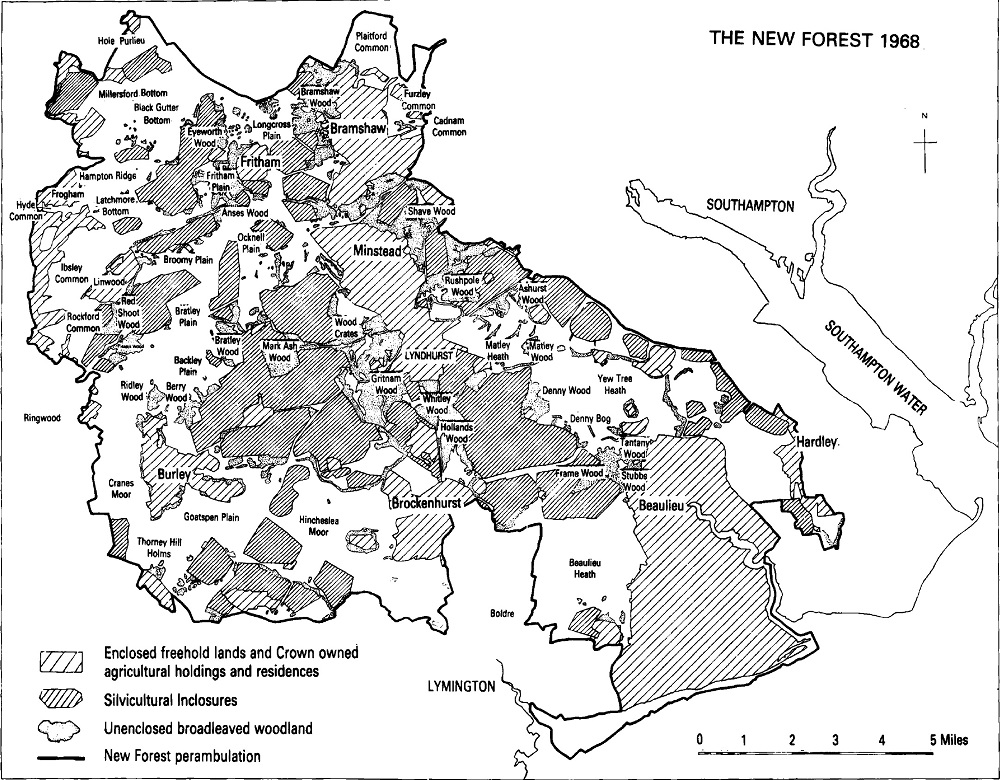

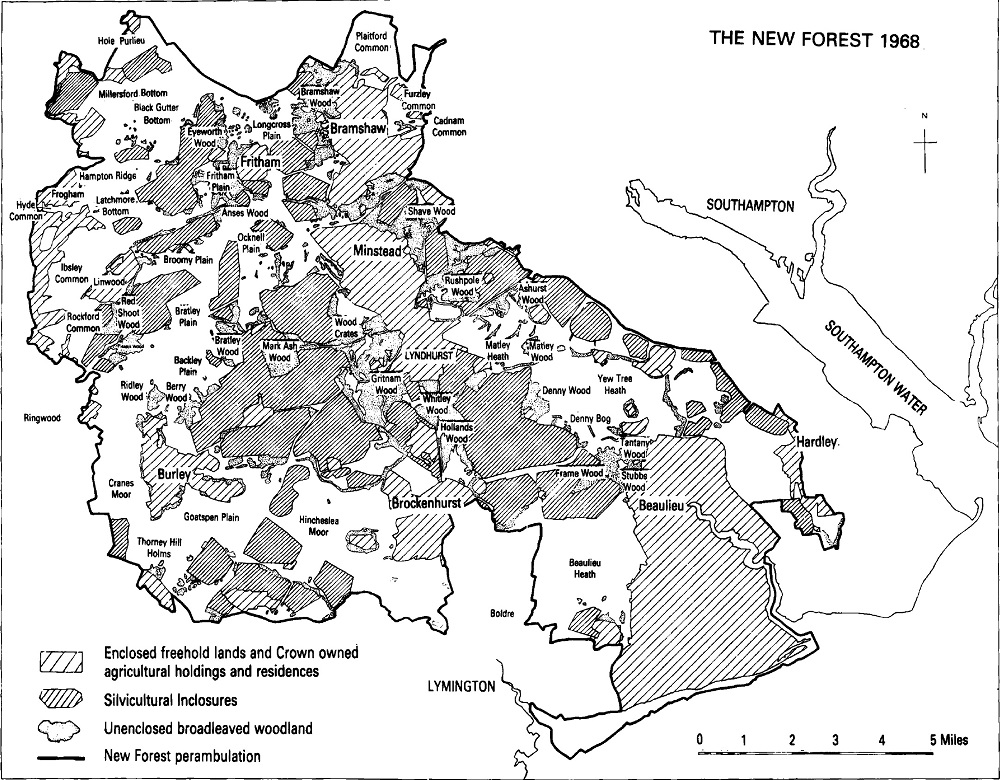

Fig. 1. The New Forest and Major Settlements

The crown lands, which form nearly three-quarters of the Forest, comprise most of the unenclosed land, the Silvicultural Inclosures, and numerous farm holdings. The crowns tenure of the Inclosures is not straightforward. Most (7104 ha) were enclosed under specific Acts of Parliament and are known as Statutory Inclosures. They are free of common rights only so long as they remain fenced, and at least 12% has to remain unenclosed at any one time. The crown can use them for no purpose other than silviculture. A further 814 ha comprise the so-called Verderers Inclosures, enclosed under peculiar conditions in the late 1950s and with only a limited life span. In addition there are 494 ha of crown freehold woodland, most of which seems to derive from the demesne of the manor of Lyndhurst, which was a crown manor; and 198 ha leased from adjoining estates.

summarizes information about the vegetation of the unenclosed Forest and Inclosures.

Fig. 2. Land Uses in the New Forest

I write as a biologist involved in nature conservation, and inevitably my view of the Forest is coloured by this. Thus, paramount in my mind is the extent and rate at which habitats similar to those found in the Forest have been destroyed elsewhere in Britain and Europe. Agricultural reclamation, conifer afforestation, and urban and industrial development have left few large areas of natural vegetation in the lowlands of western Europe away from the Mediterranean. The ancient woodlands, heaths and mires of the Forest are now internationally rare habitats. Let us consider them in the perspective of history.

The Woodlands

By Tudor times, comparatively little of the natural woodland cover of Britain had survived clearance, and the fragments which remained were mostly modified by long histories of management, exploitation or grazing. In the New Forest, large-scale clearance began in the late Bronze Age and something close to the present disposition of woodland and open habitats (excluding the Inclosures) was probably reached by the 13th century.