To my dear son, Maximilian

Text copyright 2019 by Lerner Publishing Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. International copyright secured. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior written permission of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc., except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review .

Twenty-First Century Books

A division of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc.

241 First Avenue North

Minneapolis, MN 55401 USA

For reading levels and more information, look up this title at www.lernerbooks.com .

Main body text set in Adobe Garamond Pro 11/15.

Typeface provided by Adobe Systems.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kenney, Karen Latchana, author.

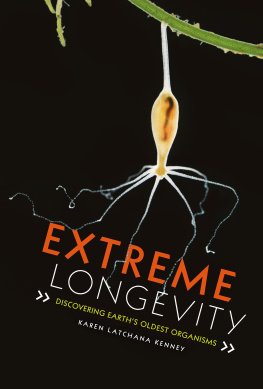

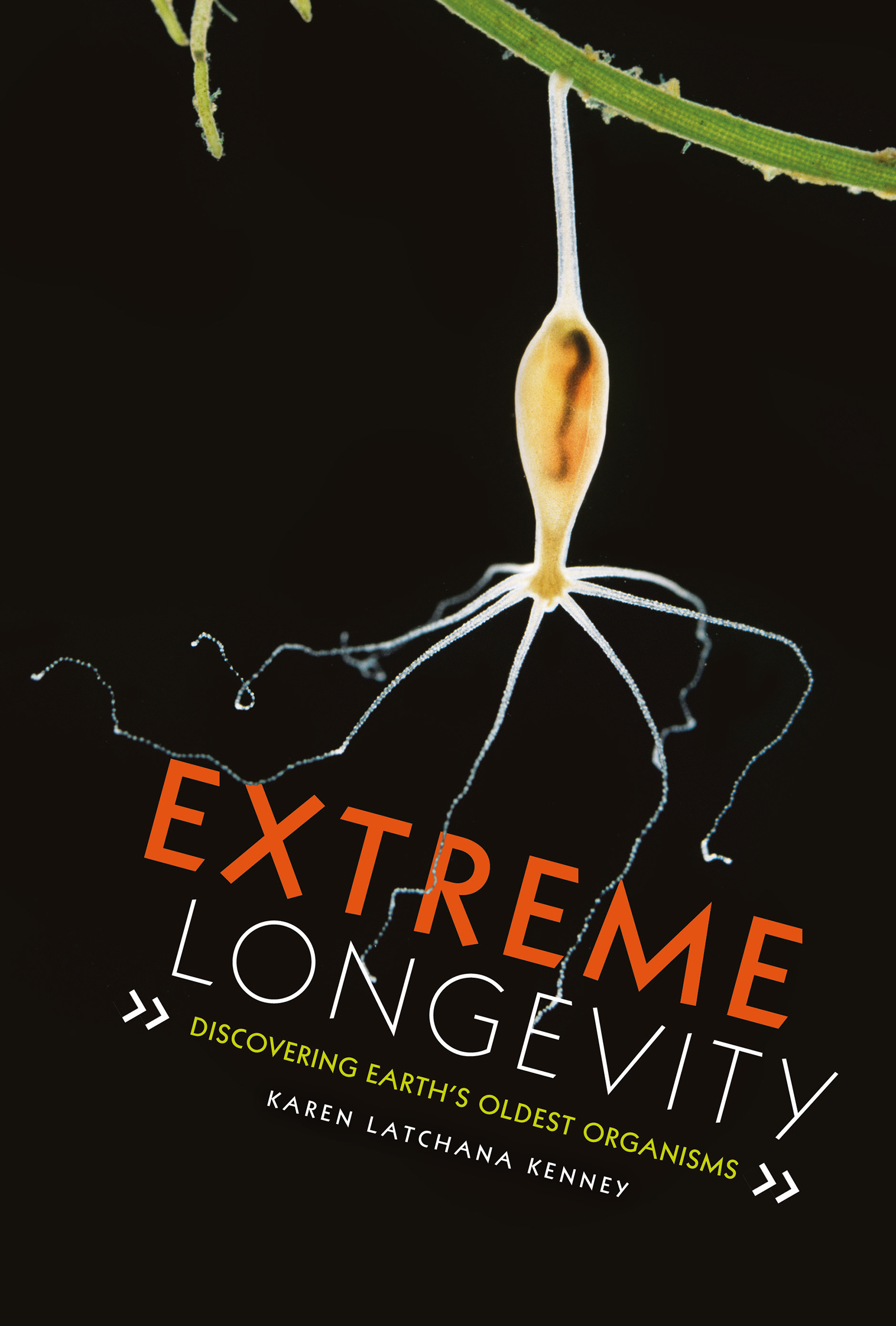

Title: Extreme longevit y : discovering Earths oldest organisms / Karen Latchana Kenney.

Description: Minneapoli s : Twenty-First Century Books, [2018 ] | Audience: Ages 1318 . | Audience: Grades 9 to 12 . | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017044278 (print ) | LCCN 2017048880 (ebook ) | ISBN 781541524781 (eb pdf ) | ISBN 781512483727 (l b : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: LongevityJuvenile literature . | AnimalsLongevityJuvenile literature . | PhysiologyJuvenile literature . | AgingGenetic aspectsJuvenile literature.

Classification: LCC RA776.75 (ebook ) | LCC RA776.75 .K4635 2018 (print ) | DDC 571.8/79dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017044278

Manufactured in the United States of America

1-43366-33178-3/28/2018

9781541538191 ePub

9781541538207 ePub

9781541538214 mobi

Contents

Introduction

The Whale That Got Away

Chapter 1

Bowhead Whales: Slow, Cold, and Very Old

Chapter 2

Greenland Sharks: Arctic Ancients

Chapter 3

A Hydra and a Jellyfish: Near Immortals

Chapter 4

Glass Sponge Reefs and Stromatolites: Back from the Dead

Chapter 5

Tuatara: Reptile Relics

Chapter 6

Pando and King Clone: Persistent Plants

Chapter 7

Inside DNA: Searching for Longevity Genes

Special Thanks

This book developed through numerous interviews with scientists working with long-lived organisms around the worldfrom throughout the United States to Canada, Denmark, Italy, and New Zealand. I thank them for sharing their extensive knowledge with me and contributing photographs for use in this book. Their studies and remarkable findings remind us that nature still has many mysteries waiting to be discovered. They include the following:

- Dr. Steven N. Austad of the University of AlabamaBirmingham

- Dr. Ferdinando Boero of the University of Salento in Lecce, Italy

- Dr. Alison Cree of the University of Otago in New Zealand

- Dr. Michael C. Grant, Dr. Jeffry B. Mitton, and Dr. Yan Linhart of the University of Colorado in Boulder

- Dr. Mads Peter Heide-Jrgensen of the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources in Nuuk

- Dr. Sally Leys of the University of Alberta in Canada

- Dr. Julius Nielsen at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark

- Dr. Joo Pedro de Magalhes at the Institute of Ageing and Chronic Disease of the University of Liverpool in the United Kingdom

- Dr. Daniel E. Martinez of Pomona College in California

- Dr. Kim Praebel of the Norwegian College of Fishery Science in Troms, Norway

- Dr. Pamela Reid of the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science in Florida

- Dr. Paul Rogers of the Western Aspen Alliance and Utah State University in Logan, Utah

- Dr. Leonel Sternberg of the University of Miami College of Arts and Sciences in Florida

Introduction

The Whale That

Got Away

I ts springtime 1890 in the icy Beaufort Sea, near the northern tip of the world. From their wooden steamship, whalers watch for massive black humps rising above shifting floes of thick Arctic ice. They listen for loud whooshing soundsthe sound of bowhead whales taking breaths before diving back down into the deep.

When the hunters spot a whale in the distance, a few of the men climb down into a small wooden boat to get in close. One whaler takes a shot from a shoulder-mounted gun, hoping for a direct hit.

The gun, a bomb lance harpoon, fires a bomb lancea metal dart with an explosive tip. It slices through the air and penetrates the thick blubber beneath the whales skin. Lodged there in bone, the tip explodes inside the whale. But the explosion does not kill the animal as it was meant to do. The whalers watch in defeat as the injured bowhead silently slips back beneath the icy water.

This underwater photo shows a bowhead whale off the eastern coast of Baffin Island, a Canadian island in the Arctic Ocean.

The whalers continue their hunt. They will never know the fate of the injured whale nor that it will outlive them, surviving in the Arctic for more than one hundred years.

Hunting Bowheads

Whaling shipslaunched from Europe, North America, and Asiaonce ruled Arctic waters. From the seventeenth century through the nineteenth century, thousands of whalers made the dangerous trip north, navigating their ships through ice floes that could crush them at any moment. They hunted different kinds of whales, but the bowhead was a prized catch. Whalers melted down the bowheads incredibly thick blubber into golden brown whale oil. One adult bowhead yielded up to 6,000 gallons (22,712 L) of the valuable oilmore than could be extracted from any other kind of whale. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, before the development of electric lights, wealthy people burned whale oil in lanterns to illuminate their homes and businesses. Mechanics used the oil to lubricate axles, gears, and other machine parts.

In addition to hunting long-lived bowheads, whalers hunted other types of whales around the world. A British artist made this painting of whalers in the South Pacific Ocean in 1836. Whaling was dangerous work, and in this painting, a whale upends the whaleboat, throwing the hunters into the sea.

Whalers also removed thin, flexible plates called baleen from the mouths of bowheads. Whales use these long plates to filter plankton, small fish, and other food from the water. In the nineteenth century, manufacturers used baleen to make fashion accessories, such as umbrella handles, hoops worn inside womens skirts, and stays (stiffeners) for womens corsets.

In the 1860s and 1870s, the whaling industry began to decline. By then US and European companies were drilling for petroleum to convert it into lubricating oils, kerosene, and other fuelsall much cheaper than whale oil. By this time bowheads and other whales were harder to find. Whalers had killed so many bowheads that the species was nearly extinctalmost gone from Earth forever. Historians estimate that before the seventeenth century, about thirty thousand to fifty thousand bowheads lived in the worlds seas. By the early 1920s, only about three thousand bowheads remained. Other whale species were equally threatened.