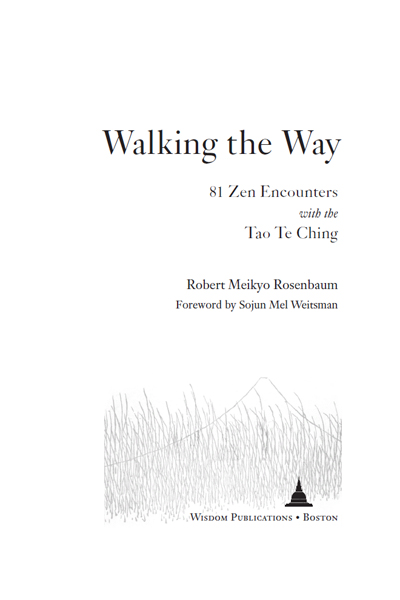

WALKING THE WAY

Wisdom Publications

199 Elm Street

Somerville, MA 02144 USA

www.wisdompubs.org

2013 Robert Rosenbaum

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photography, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system or technologies now known or later developed, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rosenbaum, Robert.

Walking the way : 81 Zen encounters with the Tao Te Ching / Robert Meikyo Rosenbaum ; foreword by Sojun Mel Weitsman.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-61429-025-3 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Zen BuddhismRelationsTaoism. 2. TaoismRelationsZen Buddhism. 3. Laozi. Dao de jing. I. Title.

BQ9269.4.T3R68 2013

294.3444dc23

2012037700

ISBN 978-1-61429-025-4

eBook ISBN 978-1-61429-026-1

17 16 15 14 13

5 4 3 2 1

Cover design by Phil Pascuzzo.

Caligraphies by Shodo Harada, courtesy of One Drop Zendo Association.

Interior design by Gopa&Ted2.

Set in Janson Text LT Std 10.4/15.5.

Wisdom Publications books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Printed in the United States of America.

This book was produced with environmental mindfulness. We have elected to print this title on 30% PCW recycled paper. As a result, we have saved the following resources: 15 trees, 7 million BTUs of energy, 1,273 lbs. of greenhouse gases, 6,905 gallons of water, and 463 lbs. of solid waste. For more information, please visit our website, www.wisdompubs.org. This paper is also FSC certified. For more information, please visit www.fscus.org.

This book was produced with environmental mindfulness. We have elected to print this title on 30% PCW recycled paper. As a result, we have saved the following resources: 15 trees, 7 million BTUs of energy, 1,273 lbs. of greenhouse gases, 6,905 gallons of water, and 463 lbs. of solid waste. For more information, please visit our website, www.wisdompubs.org. This paper is also FSC certified. For more information, please visit www.fscus.org.

This book is for my daughters.

Table of Contents

The being of a thing makes it handy;

its nonbeing lets it function.

Tao Te Ching

WHAT I HAVE always found so impressive about the Tao Te Ching is its profound simplicity. Its like coming across an ancient, weathered, solitary pine that exists above the tree line that whistles the tunes of the wind on a high mountain; it endures throughout space and time. Formed by the elements, it speaks of the harmonious interplay between heaven and earth.

Around the fourth and fifth centuries C.E., Buddhism was beginning to gain a foothold among the intellectuals and aristocracy in China. Yet the Indian scholars had a difficult time communicating the ideas written in the Sanskrit Buddhist scriptures to the Chinese. Because Chinese Taoist concepts were closest to Indian Buddhist concepts, especially the Prajna Paramita texts, the Indian scholars chose to use Taoist terms to express the Dharma. This system was called ke-yi, which means matching terms, or analogy.

Later, in the sixth century C.E., Buddhism in China separated from the Tao of Laotze and Chuangtze, and came to be understood more on its own terms. Nevertheless, the mutual influence of Taoism and Buddhism on each other continued to be a major factor in the emergence of the form of Buddhism that came to be known as Zen. It is a characteristic of Buddhism to assimilate appropriate cultural icons in a country where the Dharma arrives and to give them a place in their pantheon. As an example, the use of the term Tao, signifying the Way, is shared by both Buddhists and Taoists.

A major text of the Chinese Tsaodong school of Zen (Jap. Soto) is the Can Tong Qui (Jap. Sandokai), translated as The Merging of Difference and Unity, written by Shitou Xiquian (Jap. Sekito Kisen). Although it is a Buddhist text, the title was taken from a Taoist book. My late teacher Shunryu Suzuki, when asked if it was a Buddhist or a Taoist text, said that when a Taoist reads it, it is a Taoist text, and when a Buddhist reads it, it is a Buddhist text. Eternal truths are all-encompassing and so are able to be expressed through the lens of a relative place and time.

Immersed as we are in our busy schedules, crammed into datebooks and calendars, we sometimes lose track of how our lives play out against the background of eternity. Let me share with you one way I think about these qualities of time, specifically with regard to clocks and watches.

I am old enough to remember when digital clocks first made their appearance, tuning us in on horizontal time by isolating just one number for our convenience. For many of us it was a shock. I felt that something important was lost in just that single summary numberbut I wasnt sure why. Now I realize that although horizontal time is convenient for knowing when to do what, in a certain way it also isolates us from the whole picture.

What does a round clock, an analog clock, tell us about time? The clock face is an empty circle with a hub at its center. This circle gives form to time but because it is not yet divided it is an indicator of unified time, eternal time. We put numbers all around the circumference, and moving hands to illustrate the hours and minutes. Even so, right at the center of the clock is a still point, the fundamental truth of the moment. When we have the awareness of momentary time against the background of unified time, a clock becomes a wonderful example of the harmony of the temporal and the eternal.

No matter what time it is, it is always just now. Each moment is a moment of eternal time. This is stillness at the center of activity and activity as a function of stillness. The Tao Te Ching is like this.

The author of the present book, Robert Rosenbaum, is a long-time Zen Buddhist practitioner, qigong teacher, and psychotherapist. He has been inspired by the teachings and wisdom of Laotze and Chuangtze to contemplate his life and lifes work through the eyes of those ancient sages. In doing so, he presents eighty-one Taoist poems along with his own insights and understanding of them in a running commentary drawn from everyday life: family, work, and Dharma experiences.

The eighty-one poems from the Tao Te Ching are, to me, like a solitary mountain against a clear sky, and Bobs comments and stories are like the earth and moving water at its foot. Through this work, we see how Taoism and Buddhism complement each other, how both have shaped the authors life, and how they can do so for us as well.

Both the Tao and the Dharma tell us that the most obvious truth is right in front of our face and to look for it herenot over there. As we all know, it is the space between the notes that makes the music.

This book is a labor of love and respect, an offering to the great Taoist sages of the past, and to you, the reader. Please enjoy.

Sojun Mel Weitsman is a former abbot

of the San Francisco Zen Center

ZEN ASKS EACH OF US: how do you realize your original self? The eighty-one chapters of the Tao Te Ching offer us a guide to doing this naturally, with effortless effort. Because being yourself is ultimately Being itself, the Tao Te Ching is not a how to manual; it is an invitation for us to practice finding our Way.

Next page

This book was produced with environmental mindfulness. We have elected to print this title on 30% PCW recycled paper. As a result, we have saved the following resources: 15 trees, 7 million BTUs of energy, 1,273 lbs. of greenhouse gases, 6,905 gallons of water, and 463 lbs. of solid waste. For more information, please visit our website, www.wisdompubs.org. This paper is also FSC certified. For more information, please visit www.fscus.org.

This book was produced with environmental mindfulness. We have elected to print this title on 30% PCW recycled paper. As a result, we have saved the following resources: 15 trees, 7 million BTUs of energy, 1,273 lbs. of greenhouse gases, 6,905 gallons of water, and 463 lbs. of solid waste. For more information, please visit our website, www.wisdompubs.org. This paper is also FSC certified. For more information, please visit www.fscus.org.