A Narrative of Cultural Encounter in Southern China

A Narrative of Cultural Encounter in Southern China

Wu Xing Fights the Jiao

Hugh R. Clark

Anthem Press

An imprint of Wimbledon Publishing Company

www.anthempress.com

This edition first published in UK and USA 2022

by ANTHEM PRESS

7576 Blackfriars Road, London SE1 8HA, UK

or PO Box 9779, London SW19 7ZG, UK

and

244 Madison Ave #116, New York, NY 10016, USA

Copyright Hugh R. Clark 2022

The author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022936470

A catalog record for this book has been requested.

ISBN-13: 978-1-83998-413-6- (Pbk)

ISBN-10: 1-83998-413-9 (Pbk)

This title is also available as an e-book.

This book is dedicated to my wife Barbara,

who has supported me throughout my career

and without whom there would be no career

Contents

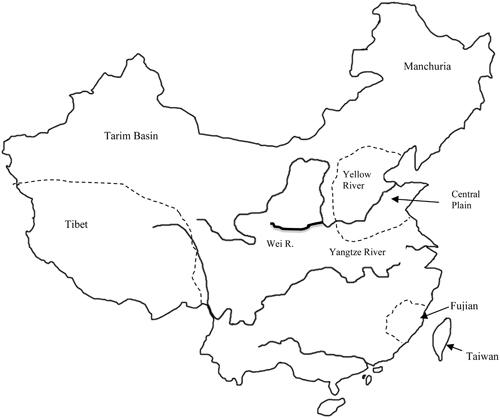

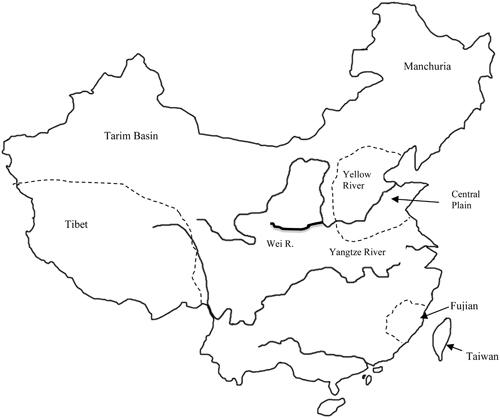

Map 0.1 Map of China, with key locations.

Neolithic Pre-History | ? ca.1500 BCE |

Shang (or Yin) dynasty | ca.1500 1046 BCE |

Zhou dynasty | ca. 1046 BCE 256 BCE |

Western Zhou | ca. 1100 772 BC |

Eastern Zhou | 772 221 BCE |

Spring & Autumn era | 772 479 BCE |

Warring States era | 479 256 BCE |

Rise of Qin | 256 221 BCE |

Qin dynasty | 221 206 BCE |

Han dynasty | 206 BCE 220 CE |

Western Han | 206 BCE 9 CE |

Wang Mang Interregnum | 9 CE 23 CE |

Eastern Han | 23 CE 220 CE |

Three Kingdoms (Wei, Shu Han, Wu) | 220 CE 280 CE |

Jin dynasty | 280 CE 420 CE |

Western Jin | 280 CE 316 CE |

Eastern Jin | 316 CE 420 CE |

Six dynasties | 420 CE 589 CE |

Sui dynasty | 581 CE 618 CE |

Tang dynasty | 618 CE 907 CE |

Tang-Song Interregnum | 878 CE 978 CE |

Song dynasty | 960 CE 1264 CE |

Northern Song | 960 CE 1126 CE |

Southern Song | 1126 CE 1279 CE |

Yuan dynasty | 1271 CE 1368 CE |

Ming dynasty | 1368 CE 1644 CE |

Qing dynasty | 1644 CE 1912 CE |

NOTE: Unless specified otherwise, all dates in this book are CE.

It has been about forty years since I first encountered the tale of Wu Xing and his battle with the jiao as I was researching my doctoral dissertation. As I shall discuss, Wu was directing a major project to drain a coastal salt marsh on the central Fujian coast. Having completed his project, so the narrative goes, the dikes that channeled fresh water through the newly reclaimed land were attacked by a jiao. Wu swore he would rescue his project by killing the beastand beast it was. Wu grabbed his sword and plunged into the water to battle. After three days the jiao and Wu were both dead. The drainage project, however, was saved and to this day remains the core of one of Chinas most productive rice regions.

I have long found the story intrinsically interesting for its own sake at several levels. Who, for example, was Wu Xing, and why did he undertake such a massive project? What was its impact on the regional ecology and economy? What became of the people who had lived with the marsh before Wu drained it? These are all questions that link to wider themes, as I shall explain. Ultimately, however, there is a question that lies at the center of Wu Xings tale: What is a jiao? It is at the core of the story, as I shall explain, yet no such creature exists in the natural world. Why does the story depend on such a mythological creature? Or could it in fact be something real?

Even if readers share my sense that these are interesting questions, none would be of much significance if there were not those broader themes, if there were not a broader insight to extract. Wu Xings project, I will suggest, is a micro-event that provides insight into the much larger process whereby the vast reaches of southern China, the land that is drained by the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River basin as well as the adjacent littoral regions that frame that basin, were folded into the larger framework that today is China. Long ago the South, as I shall call that vast area, was home to a wide array of local and regional cultures. Although some endure to the present, especially in the uplands of the farther southwest, few retain the cultural authority they once had. For much of the last millennium the orthodox narrative, one that has been strongly embraced by the contemporary Chinese state, has maintained that the diverse cultures of the ancient south were subsumed into the single culture of the empire, within which they lost their distinct identity. As we shall see, however, it was not that simple. Although many ancient identities have been lost, cultural traits have survived and have helped shape what today we call Chinese culture. The micro-event that is Wu Xing and his battle with the jiao provides an opening through which we can consider the broader encounter between that imperial culture and the complex array of cultures that once controlled the South.

This encounter is one of the most important developments in the formation of China, yet until recently it has largely been overlooked. Through the course of the second and first millennia BCE an elite culture emerged out of the complex world of Neolithic cultures that once were spread across the Central, or North China, Plain that flanks the lower reaches of the Yellow River in northern China. Through these centuries this culture, which I shall call Sinitic for it was not yet Chinese, developed a body of literature and a related set of values, the so-called classics such as the Documents, the Book of Poetry, and the Analects of Master Kong (Confucius), that even today remains at the core of Chinese culture and identity. At the same time an array of southern cultures, some quite sophisticated and powerful but none with a well-developed system of writing, and so lacking the literary heritage that defined the Sinitic culture, had emerged with their contrasting set of values and identity. Although there had been contact between these two worlds for centuries if not even millennia, they met each other most directly through the first millennium CE, and the result transformed both.

Next page