A Suitable Amount of Crime

Deplorable acts exist but does crime exist? If it does, how much is too much?

Crime is not a fixed concept and which acts are considered criminal varies historically and between societies. Any act can be defined as criminal, so crime is theoretically in endless supply.

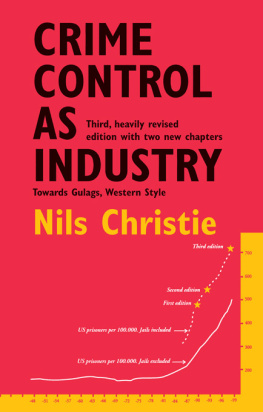

A Suitable Amount of Crime looks at the great variations between countries in what are considered unwanted acts, how many are constructed as criminal and how many are punished. It describes the differences between Eastern and Western Europe and between the USA and the rest of the world. The author denounces the size of prison populations in punitive states as a threat to human values and civil forms of societies and proposes that academics and researchers have a moral obligation to highlight that alternatives exist.

Nils Christie is a world-renowned criminologist whose work has been published in a great number of languages. This book brings together the authors years of experience studying crime and penal systems. It is written in an engaging and easily accessible style and will appeal to anyone interested in understanding contemporary problems of crime and punishment.

A Suitable Amount of Crime

Nils Christie

First published 2004

by Routledge

11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group

2004 Nils Christie

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

A catalog record for this book has been requested

ISBN 0-415-33610-4 (hbk)

ISBN 0-415-33611-2 (pbk)

Roots

So many writers circle around the same theme for much of their lives. Central for me has been the meaning of crime. What sort of phenomenon is it? Deplorable acts exist, but does crime exist? What do we mean when we say so, and under what conditions do we say it?

This was a theme for my very first piece of research, a study of guards in concentration camps. Here the questions became: When is a substance a drug, and what is it that makes the sale of certain drugs a crime and others for membership in the Chamber of Commerce?

And then, to the other end of this problem: Concepts have consequences. I have for several years kept track of prison developments within modern industrialized countries.be brought to reduce its content, whenever suitable for those with a hand on the sponge. This understanding opens up for new questions. It opens up for a discussion of when enough is enough. It paves the way for a discussion of what is a suitable amount of crime.

So much is crime, and nothing. Crime is a concept free for use. The challenge is to understand its use within various systems, and through this understanding be able to evaluate its use and its users.

* * *

Some of what here is written has earlier been presented in lectures or seminars, particularly in East and West of Europe, and in South and North of America. I have been met with great kindness and stimulating comments during these meetings. Lecturing is, in fortunate cases, a two-way process. I have learned much from these encounters. For obvious reasons, I cannot here thank all those who have taken part in this lifelong process, but I hope that some will see that they are here, in these pages. But three exceptions have to be made. Three persons mean so much to me and also for this book, that I want to express my deep gratitude. It is to my friend in Finland, Kettil Bruun, who even after his death continues as a living moral source. It is to Stan Cohen, one of my oldest friends and a source of so much inspiration. And it is to Hedda, with all she stands for.

1.1 Acts

We are four and a half million people in Norway. In 1955, we got our first statistics on crime reported to the police. The figure was shocking: close to 30,000 cases were reported. In 2002, the figure was 320,000.. The number of persons linked to these crimes has increased from 8,000 to 30,000, the number of those punished has increased from 5,000 to 20,000, and the prison population has doubled compared to its lowest point after World War II.

Does this mean that crime has increased? I do not know! And more important:I will never know!

1.2 The Suffocated Wife

As reported from Stockholm, a man drugged his wife, thereafter causing her death through suffocation. Then he wrote to the police, told them what he had done, and also what would be the end of the story. He would board the boat to Finland, load heavy stones on his body and jump. The letter reached the police two days later. They found the entrance door to the apartment unlocked, as the man had said in his letter. They also found his wife, as he had said. The body was cared for in the old-fashioned way cleaned, and left with a linen cloth over the face. She was 86, he 78. She had Alzheimers. He had nursed her for a long time but now she was about to be sent away. They were very close, said the family doctor. We look for the man, he is under strong suspicion for having committed a pre-planned murder, said the police.

* * *

To some this is a story of Romeo and Juliet. To others, it is one of plain murder. Let me illustrate what might be behind these contrasting interpretations by turning to some occurrences where central authority collapses.

1.3 The Fall of Central Authority

Ralf Dahrendorf (1985, pp. 13) opens his Hamlyn lecture on Law and Order with a powerful description of the fall of Berlin in April 1945:

Suddenly, it became clear that there was no authority left, none at all.

Shops were found deserted, and Dahrendorf remembers:

I still have the five slim volumes of romantic poetry, which I acquired on that occasion. Acquired? Everyone carried bags and suitcases full of stolen things home. Stolen? Perhaps taken is more correct, because even the word stealing seemed to have lost its meaning.

But, of course, it did not last:

The supreme, horrible moment of utter lawlessness was but a holding of breath between two regimes which were breathing equally heavily down the spines of their subjects. Like the fearful ecstasy of revolution, the moment passed. While yesterdays absolute law became tomorrows absolute injustice and yesterdays injustice tomorrows law there was a brief pause of anomie, a few days, no more, with a few weeks of either side first to disassemble then to re-establish norms.

My own memories of surrendering capitals are different. My memories are from Oslo, exactly five years earlier. During the night of 9 April 1940, alarms had continuously sounded to warn us that bombs might fall. I can still feel in my stomach how relieved I was: Now my father would have no time to fuss about a dangerous looking letter which remained undelivered in my pocket, a letter, I believed, about my lack of progress in the German language. And soon more good news followed: The school was closed and was to remain so. On my way home from that closed school I got an unexpected opportunity to practise my bad German. A car stopped. Two German officers asked politely for my assistance to and an address. Equally politely, I helped them.

![Agatha Christie [Agatha Christie] - Problem at Pollensa Bay](/uploads/posts/book/140367/thumbs/agatha-christie-agatha-christie-problem-at.jpg)