EARLY BIRD BOOKS

FRESH EBOOK DEALS, DELIVERED DAILY

LOVE TO READ ?

LOVE GREAT SALES ?

GET FANTASTIC DEALS ON BESTSELLING EBOOKS DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX EVERY DAY!

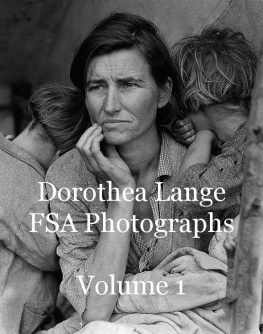

The Philosophy of Historiography

John Lange

Contents

Prologue

Part One: Preliminary Considerations

I. Introduction

1. The Proximity of the Past

2. The Limitations of the Individual

3. The Inducing Brain

4. Trajectory and the 5-D Map

5. The Importance of Comprehension

6. The Urgency of Comprehension

II. Some Distinctions

1. Historia

2. History

3. History, Again

4. Historiography

III. Studies and Metastudies

IV. Analytic vs. Speculative Philosophy of History

V. Varieties of History

1. Types

2. Agendas

1. Reportorial

2. Explanatory

3. Didactic

4. Inspirational

5. Polemical

6. Hagiographical

7. Judgmental

8. Illuminative

9. Recollective

10. Protective

11. Entertainment

12. Response to Life

13. Contextualization

14. The Satisfaction of Curiosity

Part Two: Logic and Semantics

I. Logic

II. Semantics

Part Three: Metaphysics

I. Monisms and Dualisms

II. Ontology: The Basic Ontic Hypothesis

1. Problematicities of Time

2. Past, Present, and Future

III. Causality: The Roots of Why

IV. Progress, Plan, and Pattern

1. Progress

1. Means/Ends Sufficiencies

2. Not All Change is Progress

3. Criteria-Relevant Considerations

4. Some Concepts of Progress

5. Some Challenges to Progress Theory

6. Some Dangers of Progress Theory

2. Plan

3. Pattern

1. Prolegomena

2. Pattern Potentiality

3. Pattern Triviality

4. Relevant Pattern

5. Varieties of Pattern

6. Detectability

Part Four: Epistemology

I. Historical Statements

II. A Theory of Historical Statements

III. Ancillary Observations: Process and Historical Event

IV. Truth

V. Skepticism

VI. Evidence: Some General Considerations

1. The Person

2. The Process

3. Selection

VII. The Dubiety Dilemma

VIII. Knowledge

1. Problematicities

2. Evidence: Some Particular Considerations

1. The Evidence Predicate

2. The Transcendence of Evidence

3. Evidential Conflict

4. Evidential Change

5. The Assessor of Evidence

6. The Assessment of Evidence

3. Levels of Knowledge

IX. Explanation

1. Causal-Thread Analysis

2. Elucidation

3. Explaining How

4. Colligation

5. Deductive/Nomological Explanation

6. Rational Explanation

X. Historiography and Objectivity

XI. The Cognitivity Status of Historiography

1. Preliminary Considerations

2. Particular Considerations

1. Methodology

2. Intent

3. Time-and-Place Stance

4. Subject Matter

5. Law-Boundedness

6. Explanations

7. Outcome Statements

8. The Objectivity Problem

9. Accessibility

3. The Classification of Historiography

Part Five: Axiology

I. Preliminary Considerations

II. Ethical Taxonomy

III. Systemic-Process Morality

IV. An Examination of Some Arguments Pertinent to the Cognitivity of Axiological Judgments ... 446

1. Background Considerations

1. Fact/Value Dichotomization

2. Is/Ought

3. Open-Question Argumentation

2. Some Arguments

1. Linguistic

2. Intuitional

3. Anthropological

4. Species Relativity

5. Presupposition of Science and Technology

6. Human Consciousness and the Imperative to Action

7. The Possibility of Axiological Error

8. Nonaxiological/Axiological Belief Convergence

9. Societal Prerequisites

10. The Implausibility of an Alternative

3. The Relevance of Axiology to Historiography

Part Six: Aesthetics

Epilogue

Prologue

There are these passengers on a ship, you see. It might be a ship, but perhaps not. If it is a ship, it is not clear it has a rudder. It may drift with currents, responsive to dynamics with which we are not familiar. Is the ship on some course, arranged on a captains bridge, to which we have no access? Could we ourselves take the helm? We have some sense of where the ship has been, put together from fragments, abetted by shrewd guesswork. But we cannot, as yet, find the helm, and if this were managed, somehow, it is not clear what course we might chart, or if, given the sea, the winds, and such, we might inadvertently guide the ship into waters unforeseen and best avoided. Perhaps most interestingly, most of our fellow passengers are unaware of the existence of the ship, and live, and replicate, and die, in their cabins, unconcerned with the ship and its course, or whether it has a course. Perhaps they are the wisest of all. But that is not clear.

Part One: Preliminary Considerations

I. Introduction

It is amazing that one of the most neglected domains of philosophical inquiry is that to which one would expect to find addressed constant and profound attention, namely, the multiplex histories of which we find ourselves the product.

It is not altogether obvious why this should be the case.

Consider, for example, the philosophy of science. That is, assuredly, an important and justifiably prestigious discipline within the philosophical enterprise; it is honored with considerable and well-deserved attention, and has profited, happily, from the labors of a number of unusually gifted philosophers. One begrudges her nothing, but her eminence does, given inevitable comparisons, surprise one. Why so much interest there? Or, perhaps better, why not similar interest elsewhere? Certainly science affects our lives and illuminates our understanding; it gives us aspirin and atomic weaponry, jet engines and drip-dry shirts, fountain pens, if anyone remembers such things, and computers, and life-saving surgery and poison gas. It improves immeasurably the quality of our lives and puts the means of universal extermination in the hands of sociopathic lunatics. Surely it deserves philosophical attention, and who has not wondered about stars and space, galaxies and quarks, such things. To try to philosophically grasp such an endeavor, to consider this remarkable path to knowledge, is an estimable inquiry. On the other hand, science has a bottom, so to speak, regardless of whether or not one gets there. It ends somewhere; it is finite. Somewhere the last fact lurks. Perhaps history has, too, so to speak, a bottom, but the complexities of understanding her are immeasurably deeper, and, perhaps, of greater importance. In history there may be no last fact. And, if there is, it is unlikely to be found. Atoms were presumably no more about in the time of Sargon of Akkad than they are today. But historys lessons of aggression and imperialism may weigh more heavily in speculations concerning human survival than valence bonds and molecules. Quarks were about when Buddha sat beneath a shade-giving tree and Jesus preached in Galilee. Quarks were doubtless much the same then as now, but history is different. Perhaps the prestige of science redounds to the prestige of the philosophy of science. Or perhaps the comparative simplicity of science encourages the moths of scholarship. It may be something one can get ones hands on. Perhaps it is a bit like the wonders and glories of mathematics, so attractive to fine minds searching for stability, beauty, and a refuge from a messier, more dangerous world. The number two, for example, is congenial. It can be relied on. It stands still, so to speak, and exceeds one and refuses to invade three. It is always there. You can count on it. In any event, whatever may be the causes here, whether psychologically explicable or a simple matter of a planets biographical idiosyncrasies, we confront the anomaly that an area which is most telling, and the most undeniably momentous, seems remarkably, and perhaps unconscionably, comparatively neglected. There are, of course, philosophical intrusions into the human past, and its endemic problematicities, studies undertaken by vital and astute minds, but there are too few troves in this area, certainly proportionately, and those that exist are today commonly neglected. Ratios are involved, of course. My claim here is twofold, first, history, as a discipline, is enormously important, even cognitively fundamental, and, secondly, she is woefully undervalued and understood. It is the philosophers job to remedy to some extent, subject to his limitations, this defect. This is not to compete with the historian, no more than the philosopher of science competes with the scientist. The point here is to try to understand history, and historiography. Thus the title of this book, the Philosophy of Historiography.