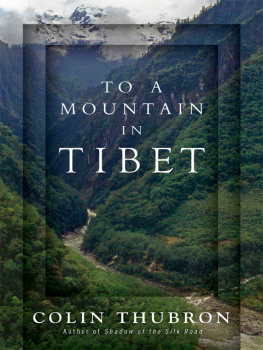

PILGRIMAGE IN TIBET

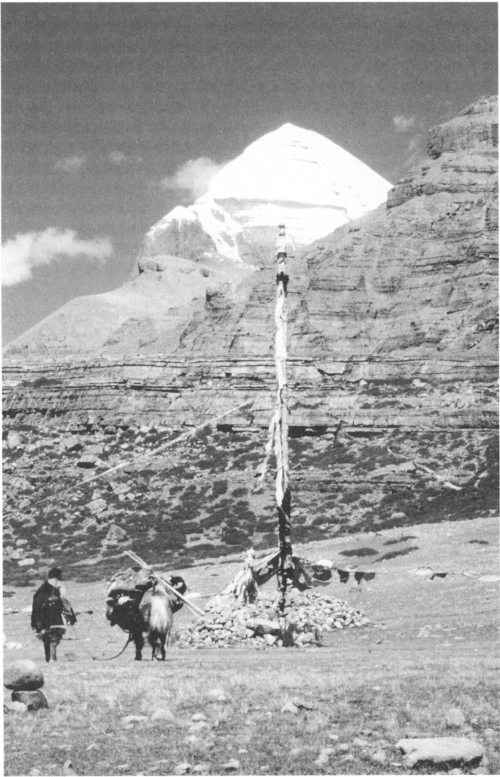

A Tibetan pilgrim approaching the giant flagpole at Tarboche on the circuit of Mount Kailas. Photo by A.C. McKay.

PILGRIMAGE IN TIBET

Edited by

Alex McKay

First published in 1998

by Curzon Press

Published 2013 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Editorial matter 1998 Alex McKay

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book has been requested

ISBN 13: 978-0-700-70992-2 (hbk)

Contents

A.W. Macdonald

A.C. McKay

K. Buffetrille

W. van Spengen

J. Clarke

P. Kvrne

H. Havnevik

W. Callewaert

B. Steinmann

A. Loseries-Leick

A. McKay

Peng Wenbin

Acknowledgements

The early inspiration for this work came from my own Indo-Tibetan travels, after which Dr Humphrey Fisher, of the School of Oriental and African Studies (London University), initially guided me into pilgrimage studies. My thanks are also due to Prof. Timothy Barrett and Dr Werner Menski at S.O.A.S., and in particular to Prof. Peter Robb and Dr Julia Leslie for their advice and support over a number of years.

This work was produced during a Leverhulme Trust (U.K.) fellowship at the International Institute for Asian Studies, in Leiden, the Netherlands, and a further IIAS fellowship. It has benefitted from the financial support of the IIAS and I am also indebted to several other institutions for support during fieldwork in the Himalayas and during its completion: the British Academy and in particular the Spalding Trust (U.K.), along with that of Malcolm Campbell (Curzon Press), for his faith in this project. None of the above are, of course, responsible for the content and opinions expressed herein. Unpublished Crown Copyright documents from the Oriental and Indian Office Collection appear by permission of Her Majestys Stationery Office.

For their assistance during my fellowship in Leiden, my thanks are due to the following authorities and staff of the IIAS: Professors Wim Stokhof and Frans Hsken, drs Paul van der Velde and Sabine Kuypers, and to Esther Guitjens, Marianna Langehenkel, Karen van Belle-Foesenek, Jennifer Trel, Kitty Yang-de Witte, Ilse Lasschuijt and Automation Officer Manuel Haneveld for his skills in removing bugs from the computer.

The authors of articles herein were participants at the Pilgrimage in Tibet conference, which was held in Leiden in September 1996 with the support of the IIAS. My thanks are due to all of the participants, observers and guests for their contributions to that conference, and in particular to the respondents, Professor A.W. Macdonald (Paris) and Dr Toni Huber (Virginia), for their advice during and since that time. Others whose contributions have been of assistance include John Bray, Mona Schrempf, Peter Richardus and Drs Reinhold Grunendahl (Goettingen), Peter Verhagen (Leiden), Michael Aris (St. Antonys College, Oxford), Professors T.E. Vetter, B.C.A. Walraven and W.J. Boot and, in particular, Emeritus Professor Jan Heesterman for his insight and ideas.

Finally, I wish to thank my wife, Jeri McElroy, for her enthusiastic support and understanding during this project.

A.C. McKay

Leiden 1997

Pilgrimage observed

The papers brought together in this volume all resulted from the meeting so ably organised by Alex McKay at the International Institute for Asian Studies in Leiden in September 1996. They bear witness to a current upsurge of interest in Tibetan pilgrimage in the university microcosms of several countries. However they also testify to the emergence in the West of a new type of scholar who is not always a member of a university faculty. From the days of Eugne Burnouf to those of J.W. de Jong we were assured that the proper way to study Buddhism was to read, edit and translate its textural legacy. Closer in time Gregory Schopen has asked for two cheers for Epigraphy and Archaeology.1 But by and large until very recently what Buddhists did and do has not been a primary preoccupation among those who haunt or gain their living in the groves of Academe. For long anthropologists were in a minority in the fields of Buddhist Studies and they were not expected to display any great philological talent. Such scholars as Richard Gombrich, who addressed himself to both Buddhist precepts and practices were rare in those days.

Today the scholarly scene has changed: anthropologists too read Buddhist books. Not content with visiting pilgrimate-sites, some even go on pilgrimage, speak the local language and read the pilgrims Guides in the text. Such Guides find translators in other continents than those in which they are composed.2 The genre dkar chag has recently been studied by Dan Martin.3 Katia Buffetrille has participated twice in the pilgrimage around A-myes Rma-chen and has demonstrated, in a definitive manner, that what is in the relevant guide-books is not always an adequate account of the local landscapes and its religious features, nor is it a reliable guide to pilgrims ritual behaviour.4

Textual study is no longer enough: the relevant texts and manuscripts must also be adjusted to the cultural context of their creation. A good over-view of such texts has been given by Toni Huber: all traditional Tibetan genres, he writes, depend upon and invoke two principal sources of authority to identify sacred sources. The main type is visionary authority, based upon pure visions (dag-snang) of particular landscapes experiences by Tantric lamas in altered states of consciousness, during meditations, dreams and so forth. The gap which exists between a pilgrims mundane experience of a holy place and the splendored dag-snang type visionary accounts of an environments sublime features and properties is technically explained by authors in terms of traditional theories of graded perceptions and cognitive abilities which are related to an individuals karmic (i.e. moral) status, degrees of embodied psycho-physical defilement (sgrib-gnyis) and thus their extent of spiritual progress towards awakening. The second type is prophetic authority in the form of citation and analysis of prophecies (lung-btsan) reputedly made by Buddhas, deities, recognised saints or highly realized lamas about the identity of particular holy places.5

If the relationship between guide-books and landscape has been clarified, and the ethnographic description of pilgrims behaviour considerably improved, it is still difficult for the Western researcher to formulate valid generalisations about what pilgrims whether illiterate or not actually experience at any given site. Pilgrims even when they move in groups or come from the same village, are a mixed lot, some being more mystically inclined than others, some having read more, meditated more deeply, heard more tales and teachings than others. If believers among them see more and something else than what is in front of their eyes, there seems to be a quasi universal need among human beings to people landscapes with stories.