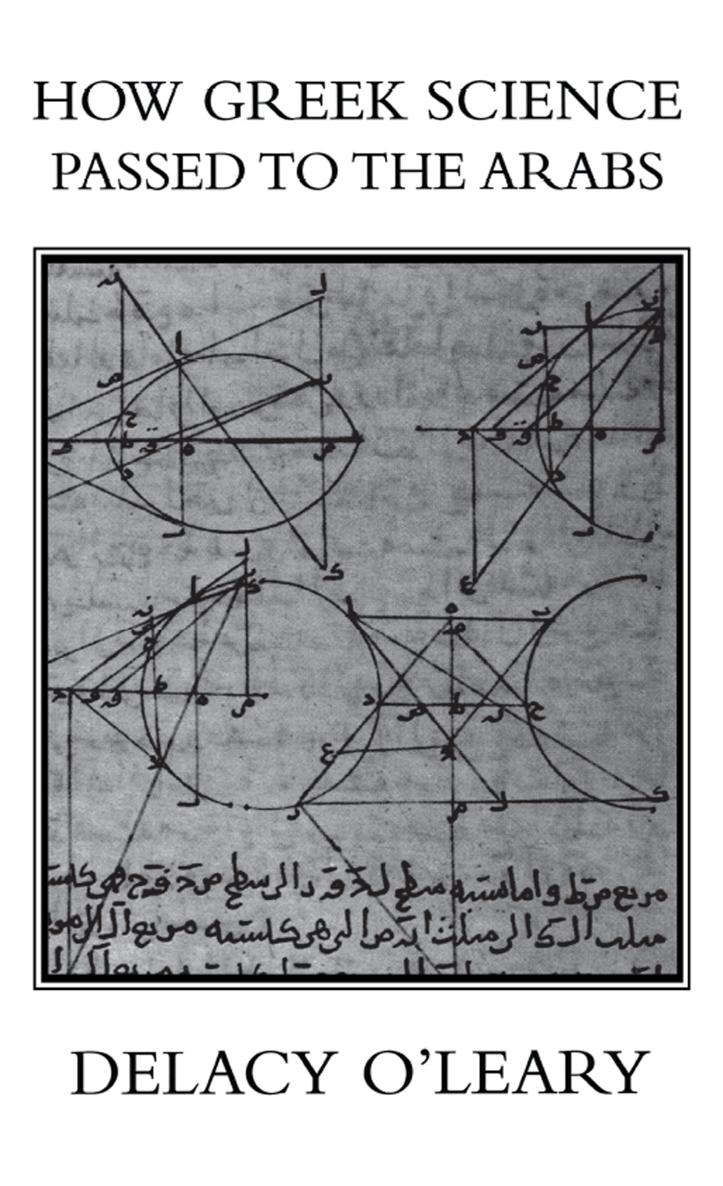

HOW GREEK SCIENCE PASSED TO THE ARABS

The history of science is one of knowledge being passed from community to community over thousands of years, and this is the classic account of the most influential of these movements how Hellenistic science passed to the Arabs where it took on a new life and led to the development of Arab astronomy and medicine which flourished in the courts of the Muslim world, later passing on to medieval Europe. Starting with the rise of Hellenism in Asia in the wake of the campaigns of Alexander the Great, OLeary deals with the Greek legacy of science, philosophy, mathematics and medicine and follows it as it travels across the Near East propelled by religion, trade and conquest. Dealing in depth with Christianity as a Hellenizing force, the influence of the Nestorians and the Monophysites; Indian influences by land and sea and the rise of Buddhism, OLeary then focuses on the development of science during the Baghdad Khalifate, the translation of Greek scientific material into Arabic, and the effect for all those interested in the history of medicine and science, and of historical geography as well as the history of the Arab world.

The late DELACY OLEARY was a well-known Arabist and published many works on the history of the Arab world.

www.keganpaul.com

THE KEGAN PAUL ARABIA LIBRARY

ARABIA AND THE ISLES

Harold Ingrams

STUDIES IN ISLAMIC MYSTICISM

Reynold A. Nicholson

LORD OF ARABIA: IBN SAUD

H. C. Armstrong

AVARICE AND THE AVARICIOUS

Abu Uthman Amr ibn Bahr al-Jahiz

TWO ANDALUSIAN PHILOSOPHERS

Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Tufayl & Abul Walid Muhammad Ibn Rushd

THE PERFUMED GARDEN OF SENSUAL DELIGHT

Muhammad ibn Muhammad al-Nafzawi

THE WELLS OF IBN SAUD

D. van der Meulen

ADVENTURES IN ARABIA

W. B. Seabrook

THE SAND KINGS OF OMAN

Raymond OShea

THE BLACK TENTS OF ARABIA

Carl S. Raswan

BEDOUIN JUSTICE

Austin Kennett

THE ARAB AWAKENING

George Antonius

ARABIA PHOENIX

Gerald De Gaury

HOW GREEK SCIENCE PASSED TO THE ARABS

DeLacy OLeary

SOBRIETY AND MIRTH

Jim Colville

IN THE HIGH YEMEN

Hugh Scott

ARABIC CULTURE THROUGH ITS LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE

M. H. Bakalla

IBN SAOUD OF ARABIA

Ameen Rihani

HOW GREEK SCIENCE PASSED TO THE ARABS

De Lacy OLeary

First published in 2001 by

Kegan Paul Limited

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Kegan Paul, 2001

All Rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electric, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying or recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Applied for.

ISBN 13: 978-0-710-30747-7 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-138-97205-6 (pbk)

CONTENTS

THERE is a certain analogy between civilization and an infectious disease. Both pass from one community to another by contact, and whenever either breaks out, one of our first thoughts is, Where did the infection come from? In both alike there is the unanswered question, Where did it first originate?do all outbreaks trace back to one primary source, or have there been several independent starting points?

In reading the autobiography of that distinguished orientalist Sir Denison Ross, there is a letter received from some inquirer which contains the sentence remarking what a good thing it would be if we could find out how, and in what form, the Greek and Latin writers found their way to the ken of the Arab or Persian or Turkish student (Sir Denison Ross, Both Ends of the Candle, n.d., p. 286). The author of the book makes no comment on this letter, but it may be noted that the way in which Greek literature passed to the Arabs and Persians, thence to the Turks, is not so unexplored as the letter suggests, and it may be traced with tolerable certainty, as it is hoped will appear in the following pages. No doubt it is a commonplace English convention which causes the writer to group Greek and Latin writers together: it does not appear that Latin writers ever did pass to the Arabs or other orientals, the transmission of ancient culture was concerned with Greek alone, and the Greek writers who influenced the oriental world were not the poets, historians, or orators, but exclusively the scientists who wrote on medicine, astronomy, mathematics, and philosophy, the type of scientific thought which does not always come foremost when we speak about classical literature. In the days when the Arabs inherited the culture of ancient Greece, Greek thought was chiefly interested in science, Athens was replaced by Alexandria, and Hellenism had an entirely modern outlook. This was an attitude with which Alexandria and its scholars were directly connected, but it was by no means confined to Alexandria. It was a logical outcome of the influence of Aristotle who before all else was a patient observer of nature, and was in fact the founder of modern science. It had its germs in older thought, no doubt, in the speculations of quite early philosophers about the origin and world and its inhabitants, animals as well as men, but it was Aristotle who introduced what may be called the scientific method.

In entering upon this inquiry it may be premised that there are at least three threads very closely interwoven. In the first place there are Greek scientific writers whose books were translated into Arabic, studied by Arab scholars, and made the subject of commentaries and summaries: in such cases the line of transmission is clear. Then there are conclusions and scientific principles assumed and developed by Arabic writers who do not say whence they were derived, but which can only be explained by reference to a Greek (Alexandrian) source. Yet again, there are questions and problems raised which the Arabs dealt with in their own way, but which never would have occurred to them unless they had been suggested by earlier Greek thinkers who had tried to solve similar difficulties, but approached their solution in a different way.

Greek scientific thought had been in the world for a long time before it reached the Arabs, and during that period it had already spread abroad in various directions. So it is not surprising that it reached the Arabs by more than one route. It came first and in the plainest line through Christian Syriac writers, scholars, and scientists. Then the Arabs applied themselves directly to the original Greek sources and learned over again all they had already learned, correcting and verifying their earlier knowledge. Then there came a second channel of transmission indirectly through India, mathematical and astronomical work, all a good deal developed by Indian scholars, but certainly developed from material obtained from Alexandria in the first place. This material had passed to India by the sea route which connected Alexandria with north-west India. Then there was also another line of passage through India which seems to have had its beginning in the Greek kingdom of Bactria, one of the Asiatic states founded by Alexander the Great, and a land route long kept open between the Greek world and Central Asia, especially with the city of Marw, and this perhaps connects with a Buddhist medium which at one time promoted intercourse between east and west, though Buddhism as a religion was withdrawing to the Far East when the Arabs reached Central Asia. Further, there were some scattered minor sources, unfortunately little known, such as the city of Harran, an obstinately pagan Greek colony planted in the middle of a Christian area, which probably made its contribution, though on a smaller scale.