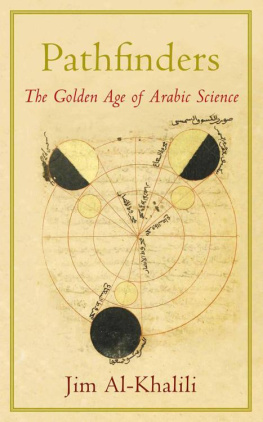

JIM AL-KHALILI

Pathfinders

The Golden Age of Arabic Science

ALLEN LANE

an imprint of

PENGUIN BOOKS

ALLEN LANE

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario,

Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park,

New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

www.penguin.com

First published 2010

Copyright Jim Al-Khalili, 2010

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All rights reserved.

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book

ISBN: 978-0-14-196501-7

To Julie

He who finds a new path is a pathfinder, even if the trail has to be found again by others; and he who walks far ahead of his contemporaries is a leader, even though centuries pass before he is recognized as such.

Nathaniel Schmidt, Ibn Khaldn

List of Figures

List of Plates

Preface

Sargon, king of Akkad, overseer of Ishtar, king of Kish, anointed priest of Anu, king of the country; he defeated Uruk and tore down its walls. Lugalzaggisi, king of Uruk, he captured in this battle, and brought him in a dog collar to the gate of Enlil.

Ancient text

An hours drive south of Baghdad lies the town of Hindyya. This was where I spent my last few happy teenage years in Iraq before leaving for good in 1979. The town takes its name from the Hindyya Barrage, which was built across the Euphrates in 1913 by the soon to be departing Ottomans. I have an abiding and powerful memory of this bridge. On cool autumn days I would skip afternoon school with my three best friends, Adel, Khalid and Zahr il-Dn, and walk across the Barrage to the riverside tourist resort on the opposite bank. We would buy a six-pack of Farda beer and sit down by the water discussing football, philosophy, movies and girls.

Those happy days contrast dramatically with a second powerful image that is seared into my memory and which took place during the first Gulf War of 1991. I remember watching a CNN news report showing footage of a gun battle in Hindyya in which a lone and terrified woman was trapped in crossfire while walking across the Barrage. For most viewers this would have been just another scene depicting the horrors of war in a far-off land. But for me, instantly recognizing the setting, it suddenly brought home the reality of the plight of the country I had left behind twelve years earlier. I had walked past the spot where this helpless woman now stood frozen in terror dozens of times.

But that was a world away. As I write, I have yet to return to Iraq. I say as I write for I have not ruled out a brief visit at some point in the future when, coward that I am, I deem it safe enough.

The year I left Iraq was a momentous one in the Islamic world. In 1979 Anwar Saddat of Egypt and Israels Menachem Begin signed a peace treaty in Washington, the first Islamic republic was created in Iran after the deposed shah fled to Cairo, the holy city of Mecca witnessed a gun battle to put down a fundamentalist insurrection following the killing of hundreds of pilgrims, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan and the Iranian hostage crisis began in the US embassy in Tehran. During all this turmoil, Saddam Hussein had taken over the presidency of Iraq from Field Marshal Muhammad Hassan al-Bakr, thus making life a great deal grimmer for the vast majority of the population there. My family and I arrived in Margaret Thatchers Britain at the end of July exactly two weeks after Saddam had come to power. We had escaped just in time, as it turned out, for within months he had declared war on Iran. Had we not left that summer, my brother and I would undoubtedly have been conscripted to fight in that pointless and terrible conflict and I doubt that I would have lived to tell the tale. Having a British mother and a Shia Muslim father of Persian descent who had flirted with the Iraqi Communist movement in the 1950s marked my brother and me as undesirables, and certainly expendable frontline fodder.

And life in Iraq seems to have gone downhill ever since. Things have changed there dramatically since my childhood in the 1960s and 1970s when life for a kid from a middle-class background was comfortable and relatively easy. My father, a British educated electrical engineer, had served as an officer in the Iraqi air force. His various postings around the country meant that we were used to moving house regularly. But in the early 1970s, the ruling Baath party decreed that any Iraqis with British wives were suddenly no longer to be trusted in the armed services. So, having reached the rank of major, he now had to find work as a civilian for the first time in his adult life. He soon landed a job as the head of engineering at Mamal al-Harr, a chemical firm in Hindyya that produced artificial rayon fibres. We lived in Baghdad for a few years before eventually moving to Hindyya to spare my father the daily commute. This was fine with me. I made friends quickly, set up my new football team: the Rayon Dynamos (I still have the tatty number 9 shirt I wore) and, together with my brother, would tune in to the BBC World Service to catch the English football scores on Sports Report on Saturdays. Actually, the World Service was pretty much a constant background in our house. When possible, I would make regular visits to the British Councils library in Baghdad for my supply of English books. And I grew up knowing that living under a dictatorship was bearable, as long as you kept your head down and never criticized the government or the Baath Party, even in private.

A fun day out for my family and me was to visit the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, an hours drive south-east of Hindyya. The ruins of this mythical place held no great mystique as I had often trudged around the site on school trips. But despite the less than impressive ruins and my indifference born of familiarity, the excitement of a day away from class never lost its appeal, and the site still radiated a powerful aura that whispered of past glories too ancient for me to comprehend. Once, while on a family picnic there when I was in my early teens, we came across two chunks of clay brick, each the size of a fist and each clearly marked with ancient cuneiform writing on one surface. It is still a source of a long-running and good-natured family dispute as to whether it was my brother, my mother or I who actually picked up these bricks. In any event, my mother hid them in the bottom of our food hamper and we smuggled them back home.

This probably sounds like an outrageous case of archaeological theft. Surely we should have handed over such national treasures to the local authorities or, probably more sensibly, to the Iraqi Museum in Baghdad. But we kept them. In our defence, similar cuneiform-etched Babylonian bricks were strewn among the rubble all around us. And in comparison with the later damage wrought on the ruins of ancient Babylon first by Saddam Husseins astonishingly vulgar rebuilding of the Ishtr Gate in the 1980s, and more recently by the US forces in 2003 who levelled a whole section of one of the worlds most precious archaeological sites to create a landing area for helicopters and a parking lot for heavy military vehicles our theft seems pretty tame.