Authors Note

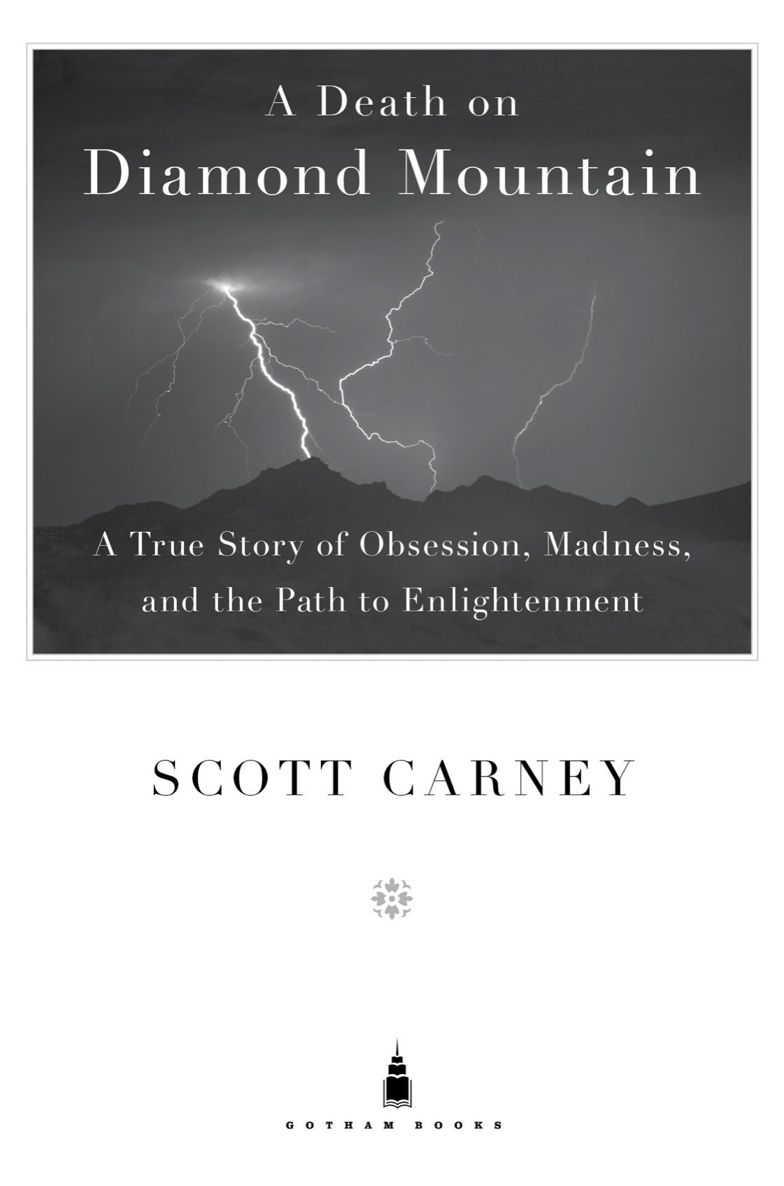

H OW MUCH SHOULD someone strive to know their own soul?

It is a question I have struggled with for the better part of a decade after an incident that taught me that intensive meditation has the potential to unleash unexpected consequences. From 1998 to 2006, I spent about three years bumping around India, Tibet, and Nepal, first as a student on an abroad program learning about Indian and Tibetan folklore, and later in backpacker hostels on the beaches of Goa and the mountain valleys of Kathmandu. Later, I dropped out of a PhD program in anthropology to lead an abroad program for American students that advertised in glossy brochures with the catchy title India: From Brahma to Buddha. I was excited to help guide young people on their journeys in a foreign land.

The highlight of the program was a ten-day silent meditation retreat in the rustic town of Bodh Gaya, the spot where Buddha achieved enlightenment while sitting under a fig tree almost three millennia ago. We studied an introductory program known in Tibetan as lamrim to learn about the karmic cycle of death and rebirth and to cultivate an attitude of compassion for all living things. We were told that this could lead the way to happiness in this lifeand perhaps enlightenment in our next.

I began studying Tibetan Buddhism on my first trip to Asia and it had helped me find my own answers to some of lifes big questions. Its focus on mortality made me realize that no matter what we believe happens after death, our time on this earth is precious. Buddhists reflect openly on death and teach that although all life ends in tragedy, the way we use our lives does not have to be meaningless. Every moment has value and meditation is one way to capture lifes fleetingness.

The first seven days of the retreat consisted mainly of breathing exercises and lectures on the Tibetan worldview. On the eighth day, the experience turned dark. The Swiss-German nun who was our instructor told us to imagine that we were decaying corpses and that the bodies of everyone we knew were bags of human shit. The exercise, which is meant to help the students develop psychic tools to use when they eventually face their own death, might sound extreme, but Tibetan meditation can get even more far-out: A practice known as chd involves meditating over actual decaying corpses in a graveyard.

When the meditations were over, I had a conversation with one of my studentsa whip-smart twenty-one-year-old Southern belle named Emily OConner (not her real name)about her experiences. She said it was the most profoundly moving experience of her life and that maybe more silence would have been better.

That night, while the other students chatted enthusiastically in the meditation room, she climbed to the roof of one of the dormitories, wrapped a khadi scarf around her face, and jumped. A student on his way to bed found her facedown on the pavement. According to the coroners report, she had died on impact.

I was charged with returning her remains to America. Somewhere along the way, the Indian police gave me her journal. On the eighth day of the retreat, shed written in flowery, well-constructed cursive, Contemplating my own death is the key. Then, a few paragraphs later, Im scared that I will have this realization and go crazy. One of the last things Emily wrote, in the same steady hand, was I am a Bodhisattvaan enlightened being that Tibetans aspire to become. She believed she was well along the road to transcendence.

There are many explanations for why Emily, my student, decided to take her own life. Maybe she had misunderstood the meaning of enlightenment. Maybe she had underlying mental instabilities that just happened to manifest themselves during intensive meditation. For all I knew, she was a Bodhisattva and continuing on her journey in another realm. However, here on earth I worried that enlightenment might not be all that it promised.

The experience changed my life, turning me toward a career as an investigative journalist. As I recounted in my book TheRed Market: On the Trail of the Worlds OrganBrokers, Bone Thieves, Blood Farmers, and Child Traffickers, my fight to preserve her body with ice and embalming fluid against the inevitability of decay made me consider the subtle line that separates the flesh of a corpse from that of a living person. Without that mysterious animating force that some people might call a soul, our bodies are little more than meat. Out of a living context, that meat is a sort of commodity in the eyes of the world. For the next five or six years, I followed that realization to what, for me, were its logical conclusions. I became a journalist and explored the growing, illegal markets for bodies and body parts.

Even as I pursued criminals across international lines, I often drifted back to the question of why my student took her life. For me, it was more difficult to understand how a technique that was supposed to make someone a more compassionate person could have such a tragic result.