This book is the product of more than two hundred interviews over four years, multiple trips to Bangladesh, and correspondence with sources in Bangladesh, Pakistan, India, the United States, the United Kingdom, South Africa, and elsewhere. We have spoken with cyclone survivors, freedom fighters, members of the Pakistani military, historians, scientists, policymakers, hotel employees, TV broadcasters, climate experts, and other individuals who all contributed valuable pieces to the puzzle.

Our archival research spans an additional seven hundred and fifty sources, including books, academic articles, reports, newspaper and magazine articles, government statements, and other publications. Some documents, like Yahya Khans service record, are presented here publicly for the first time. These sources helped contextualize our characters experiences and validate the stories we collected from eyewitnesses. For ease of reading, we do not employ in-text citations. Instead, we present the reference section in endnotes, noting the relevant text.

This book is a work of narrative nonfiction. While all details herein are true and research-based, the act of putting disparate pieces together in a way that puts the reader in the historical moment required us to make judgments at times about motivations and states of mind that are not preserved in the historical record. In some places, we condensed timelines, dialogues, competing perspectives, and peripheral details for clarity and to better bring out the essence of the events. For example, some scenes combine events that occurred over multiple days into a single narrative moment. In other places, we extrapolate minor pieces of dialogue, mannerisms, and presumable emotional responses in places where the participants themselves did not remember the specific details of a conversation that happened fifty years ago. For transparency, we have referenced all such instances in the notes section. These stylistic edits have no material bearing on the factual events we present, and responsibility for any errors or possible misinterpretations remain ours alone.

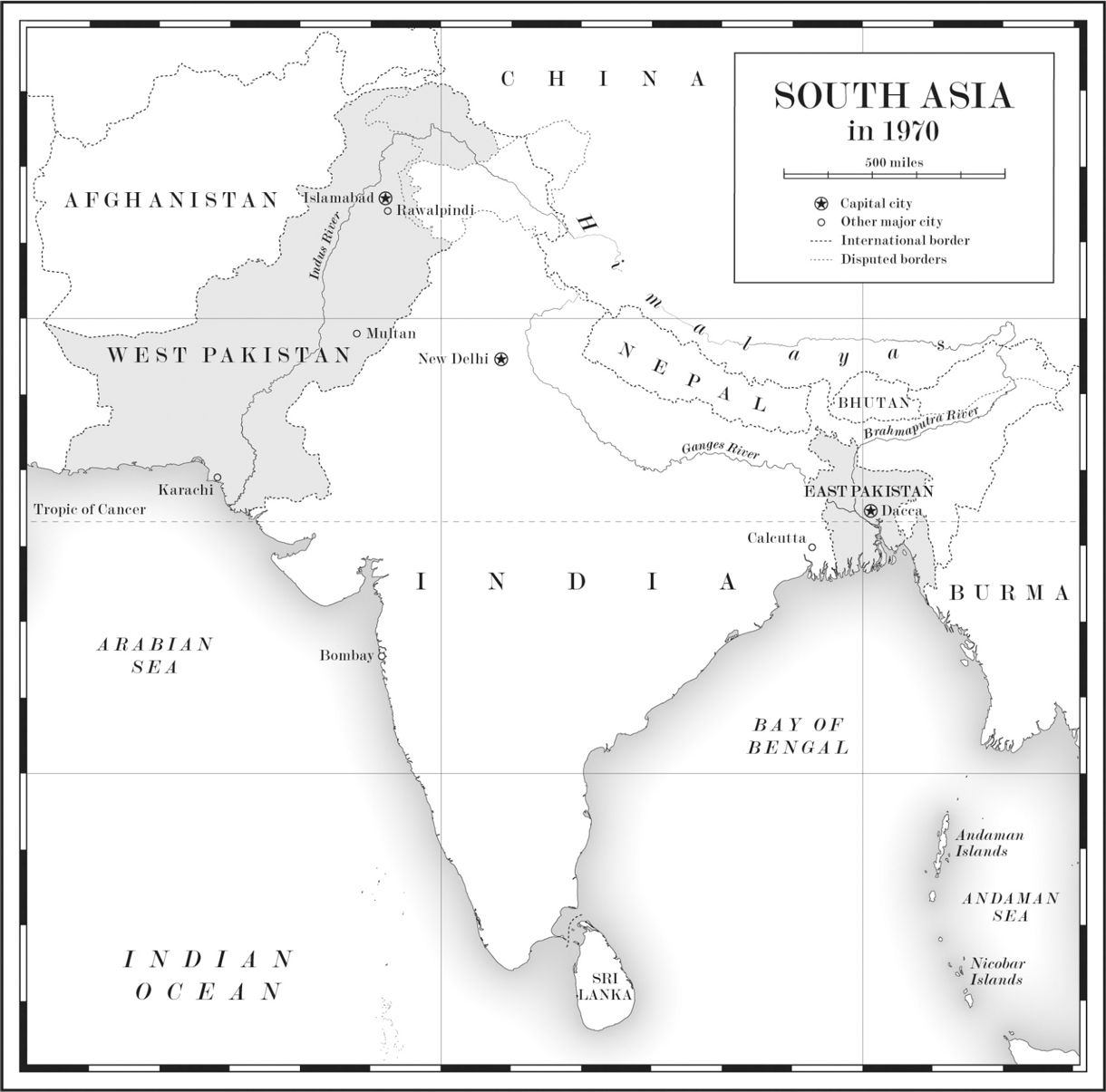

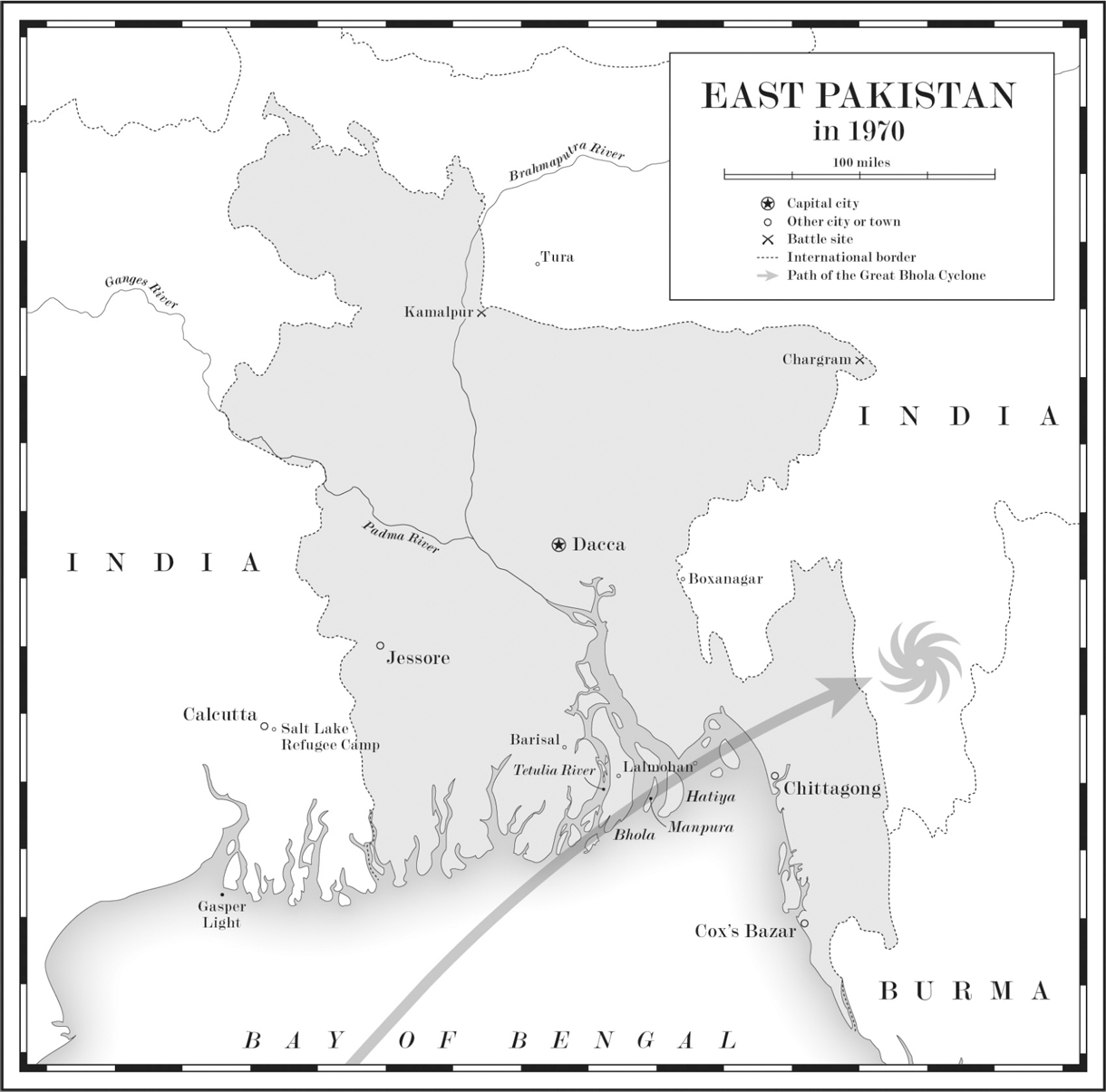

Furthermore, we opted to use the spellings of locations, military ranks, and people that were in use in 1970 in order to preserve the flavor of the moment. So cities like Kolkata and Dhaka appear in this text as Calcutta and Dacca. Similarly, we chose the spelling Manpura over Monpura, despite both spellings being in popular usage. We refer to our central sources by their first names instead of their last names to avoid the confusion that would emerge where people share common family names.

BAY OF BENGAL

NOVEMBER 11, 1970

Twenty-four hours before landfall

White mist surged across the Mahajagmitras bridge and the ships aging frame creaked with each menacing gust. The man in charge, Captain Nesari, watched the pressure fall a bit more on his ships barometer and paced the length of the control room. With its holds crammed to capacity with jute fiber and steel, the ship rocked ominously as it inched toward the open sea.

Nesari and his ship were leaving the great Hooghly River, the westernmost finger of Indias Ganges delta and one of the worlds most troublesome waterways. The Hooghly meets the Bay of Bengal at a point about thirty miles south of Calcutta, where incalculable volumes of silt wash down from the Himalayas and form a fan of ever-shifting rivers, tributaries, and temporary islands. A freighter that alights on a sandbar here might never break free.

As if to prove the point, the rusty hulls of abandoned vessels dotted the seascape. Colossal silt deposits alter the map on an almost daily basis, which is why Nesari hired the expert river pilot R. K. Das from the Port of Calcutta to navigate this stretch of water. Das deftly guided the six-thousand-ton ship through the narrow channels as the wind began to pick up.

Nesari darted his eyes back and forth between the barometer and a stack of outdated maps as he tried to estimate the coming storms strength. The stakes were high. Waiting out the weather system would add at least a day to their two-week trip to Oman. It would mean that the company would have to pay another days worth of salaries to the crew of forty-eight seamen, deplete another days worth of fuel, and stretch their already narrow profit margins to the breaking pointall potentially fireable offenses for any captain who signed off on such a cost overrun.

Then again, pushing onward out of the delta would expose the ship to the full power of whatever weather system lay just over the horizon. The worst-case scenario was too terrifying to contemplate. So Nesari had a decision to make: Would he take the risk, or would he power down?

If it was just a squall, then the Mahajagmitra would be fine. But what if they were witnessing the edge of a cyclone? Cyclonic stormscalled hurricanes in the Americas and typhoons in the Pacific Rimare especially deadly in the Bay of Bengal. Here storms spin counterclockwise, which means that any ship leaving the Port of Calcutta would have to travel directly into the center of the storms powerfacing potentially devastating wind and waves head-on. Once a ship turned southward, the wind would crash against the port side, which could capsize a vulnerable vessel.

Nesari thought of his family and then considered his first mate. David Machado wore the starched white uniform of the Indian Merchant Navy, complete with three gold stripes and a diamond on his epaulettes. Machado couldnt help cracking into a smile when he thought no one was looking. Last week, hed married the love of his life. After the ceremony in South India, the newlyweds flew to Calcutta together. Sailors like him didnt always get to pick the location of their honeymoon, yet somehow hed convinced his bride that a cruise to the Middle East would be a fine way to start their life together.

Machados wife stowed herself below deck, her heavy wedding jewelry tucked safely away in a trunk in their shared compartment. The crew knew the ancient Greek warning that women on board were bad luck. Ostensibly, this was because women caused distractions, but more superstitious sailors claimed that they also attracted misfortune and bad weather. Captain Nesari was glad that they lived in more civilized times.

It was November 11, 1970, yet despite thousands of years of seafaring, a sailors ability to predict the weather hadnt improved much since the nineteenth century. The radio was the biggest breakthrough in the last hundred years and allowed mariners to speak with other ships who were closer to dangerous weather systems. A smart navigator could triangulate a storms center by matching other ships weather reports to his ships current positiona method that wasnt so different from how truckers relayed traffic patterns to their colleagues over CB radios.

The catch was that the radio operator had to actually find another ships signal. As far as Nesari could tell, there wasnt a single transmission coming from anywhere in the Bay of Bengal. This meant that if the Mahajagmitra proceeded onwards it would be the first to brave the swells. It would be their job to report back to other vessels contemplating the journey.

Barring radio contact, Nesari had only one other tool to understand the weather system: Buys Ballots law. In 1857, the Dutch meteorologist Charles Buys Ballot invented a method for determining the direction of a storm. He wrote that if a sailor in the Northern Hemisphere stood on deck with his back to the wind, he could use his senses like a human compass. The pressure would be low on his right and high on his left, which meant that his right hand would point to the center of the systemthe most dangerous part. As long as Nesari could steer clear of that point, theyd avoid the most intense wind and waves. The ship and its crew would be safe, and theyd save valuable days at sea.