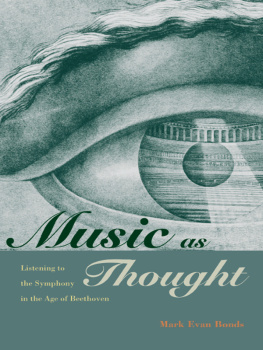

Bonds Mark Evan - Music as Thought: Listening to the Symphony in the Age of Beethoven

Here you can read online Bonds Mark Evan - Music as Thought: Listening to the Symphony in the Age of Beethoven full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Deutschland., Princeton, N.J, year: 2006, publisher: Princeton University Press, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Music as Thought: Listening to the Symphony in the Age of Beethoven

- Author:

- Publisher:Princeton University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2006

- City:Deutschland., Princeton, N.J

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Music as Thought: Listening to the Symphony in the Age of Beethoven: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Music as Thought: Listening to the Symphony in the Age of Beethoven" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Bonds Mark Evan: author's other books

Who wrote Music as Thought: Listening to the Symphony in the Age of Beethoven? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Music as Thought: Listening to the Symphony in the Age of Beethoven — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Music as Thought: Listening to the Symphony in the Age of Beethoven" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Music as Thought

Music as Thought

LISTENING TO THE SYMPHONY

IN THE AGE OF BEETHOVEN

Mark Evan Bonds

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2006 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock,

Oxfordshire OX20 1SY

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bonds, Mark Evan.

Music as thought : listening to the symphony in the age of Beethoven / Mark Evan Bonds.

p.cm.

Includes bibliographical reference and index.

eISBN: 978-1-40082-739-8

1. Symphony19th century. 2. Music appreciation. 3. MusicPhilosophy and aesthetics.

I. Title.

ML1255.B68 2006

784.2'18409034dc22 2005034091

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon

Princeton on acid-free paper.

pup.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

TO MY PARENTS

Marian Forbes Bonds and Joseph Elee Bonds

Der deutsche will seine Musik nicht nur fhlen, er will sie auch denken.

The German wants not only to feel his music, he wants to think it as well.

Richard Wagner, ber deutsches Musikwesen (1840)

Contents

Acknowledgments

I BEGAN WORK on this book during a year-long fellowship at the National Humanities Center in the Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, in 1995-96. My original project there, funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, involved gathering and translating a wide range of critical commentaries on the symphony between 1720 and 1900. Although the finished product has turned out quite differently, the opportunity to assemble and work through such a wide range of documents opened my eyes and ears to newor rather, very oldways of listening to the symphony. I am grateful to the staff of the National Humanities Center for their support, particularly to Bob Connor and Kent Mullikin, and the library staff of Alan Tuttle, Eliza Robertson, and Jean Houston, who were able to track down some unusually obscure items on my behalf.

I am also grateful to the American Academy in Berlin, where as the DaimlerChrysler Fellow during the fall of 2002 I worked on something more nearly resembling the present book. Gary Smith, Paul Stoop, Marie Unger, and the entire staff there created a setting that provided the ideal mix of sociability and solitude needed for turning an idea into a book. Thanks, too, to Elmar Weingarten and Claudia von Grothe, my godparents in Berlin who helped me to experience first-hand, through the Berlin Philharmonic, the immediacy of the continuing artistic, social, and political traditions that link an orchestra and its listeners. A semester-long fellowship from the W. N. Reynolds Foundation through the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill allowed me to remain in Berlin and continue my work there from January through June 2003. Through this fellowship, a good portion of this book happened to be written across the street from the cemetery in which Fichte and Hegel lie buried. While in Berlin, I also learned much from the students in the Blockseminar I directed at the Musikwissenschaftliches Institut of the Humboldt-Universitt on the German music festival in the nineteenth century. My thanks to Hermann Danuser for inviting me to lead this seminar and to the dozen participants, who are no doubt still among the very few of their compatriots who have read Wilhelm Griepenkerls extraordinary novel about The Beethovenians in its entirety (see chapter 5).

At the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, I am fortunate to work with exceptional colleagues, foremost among them Tim Carter, Annegret Fauser, and Jon Finson, all of whom gave useful advice in various ways and at various stages of this project. I have also benefited from the outstanding library resources and staff here, most notably Phil Vandermeer, Diane Steinhaus, Eva Boyce, John Rutledge, and Tommy Nixon. Bryan Proksch provided the graphics for the musical example.

Colleagues at other institutions have also been most generous in sharing their time and expertise with me over the years. These include Lydia Goehr (Columbia University), for stimulating conversations on Hanslick and Adorno; David Levy (Wake Forest University), for his help in securing a copy of Griepenkerls Das Musikfest and for conversations on this novella and other aspects of Beethoven reception; James Parsons (Southwest Missouri State University), for his insights on Schiller and the Ninth Symphony and for helping me to navigate the otherwise impenetrable Deutsche Staatsbibliothek; J. Samuel Hammond (Duke University), for a variety of favors great and small but mostly great; and Michael Broyles (Pennsylvania State University) and William Weber (California State University, Long Beach), for their very helpful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

My greatest thanks go to my family. Dorothea, Peter, and Andrew have seen this book through since its inception, and it has taken us many places. I can only hope that through it all I have listened half as well as they have.

Portions of chapters 1 and 2 appeared in an earlier form in an essay entitled Idealism and the Aesthetics of Instrumental Music at the Turn of the Nineteenth Century, in the Journal of the American MusicologicalSociety 50 (1997): 387-420. All translations, unless otherwise indicated, are my own.

Introduction

WHILE BROWSING in the philosophy section of a bookstore a few years ago, I noticed a large image of Beethoven on the cover of a book. My first thought was that the item had been misshelved. On closer inspection, I saw that this was indeed a book about philosophy: volume seven of Frederick Coplestons classic History of Philosophy, covering the period from the Post-Kantian Idealists to Marx, Kirekegaard, and Nietzsche. But none of those figures was on the coverit was only Beethoven. What made this all the more puzzling is that Beethoven is never mentioned in the text, not even in passing. He was on the outside of the book, but not on the inside.

Why a composer on the cover of a book about philosophy in which he does not appear? And why Beethoven? Without wishing to put too much weight on the imagination of a book-jacket designer working in the late twentieth century, I believe this image does in fact capture a whole range of connections we routinely make about Beethovens music and its capacity to say something about ideas, thought, and the pursuit of truth, even without the aid of words. These connections are more easily recognized than articulated, but generations of listeners since the composers own time have been relating Beethovens instrumental musicparticularly his symphonies, the one genre on which his legacy rests more than any otherwith ideas that go beyond the realm of sound.

This perception of instrumental music as a vehicle of ideas did not originate in responses to Beethoven or his symphonies, however. It predates the Ninth Symphony (1824), with its vocal finale about joy and universal brotherhood, and even the Eroica Symphony (1803), with its descriptive title and canceled evocation of Napoleon. The perception of the symphony as a means of thought was already in place by the late 1790s, before Beethoven had even begun to write symphonies at all. By the same token, the change cannot be ascribed to the works of any other composer, including Haydn and Mozart. This change, instead, was driven by a radically new conception of all the artsincluding musicthat emerged in German-speaking lands toward the end of the eighteenth century. People began to listen to music differently in the closing decades of the eighteenth century, and this change in listening opened up new perceptions toward music itself, particularly instrumental music.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Music as Thought: Listening to the Symphony in the Age of Beethoven»

Look at similar books to Music as Thought: Listening to the Symphony in the Age of Beethoven. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Music as Thought: Listening to the Symphony in the Age of Beethoven and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.