Lives of Great Religious Books

Thomas Aquinass Summa theologiae

LIVES OF GREAT RELIGIOUS BOOKS

Thomas Aquinass Summa theologiae, Bernard McGinn

The Dead Sea Scrolls, John J. Collins

The Bhagavad Gita, Richard H. Davis

The Book of Mormon, Paul C. Gutjahr

The Book of Genesis, Ronald Hendel

The Book of Common Prayer, Alan Jacobs

The Book of Job, Mark Larrimore

The Tibetan Book of the Dead, Donald S. Lopez, Jr.

Dietrich Bonhoeffers Letters and Papers from Prison, Martin E. Marty

The I Ching, Richard J. Smith

The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, David Gordon White

Augustines Confessions, Garry Wills

FORTHCOMING:

The Book of Revelation, Timothy Beal

Confuciuss Analects, Annping Chin and Jonathan D. Spence

Josephuss Jewish War, Martin Goodman

John Calvins Institutes of the Christian Religion, Bruce Gordon

The Lotus Sutra, Donald S. Lopez, Jr.

C. S. Lewiss Mere Christianity, George Marsden

The Greatest Translations of All Time: The Septuagint and the Vulgate, Jack Miles

The Passover Haggadah, Vanessa Ochs

The Song of Songs, Ilana Pardes

The Daode Jing, James Robson

Rumis Masnavi, Omid Safi

The Talmud, Barry Wimpfheimer

Thomas Aquinass Summa theologiae

A BIOGRAPHY

Bernard McGinn

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2014 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

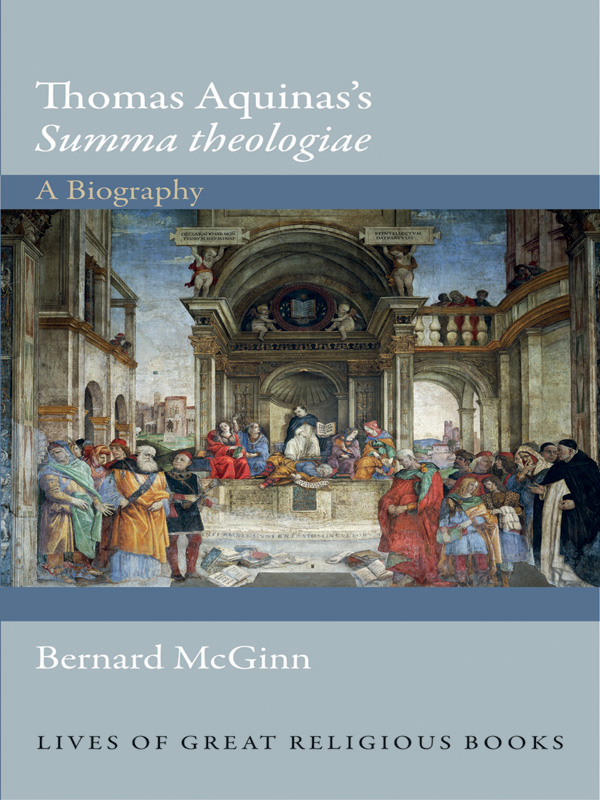

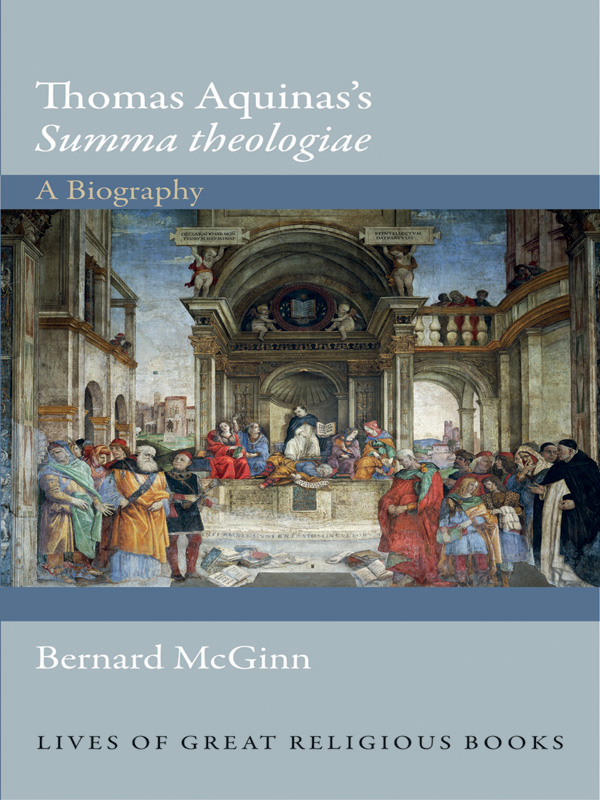

Jacket art: Triumph of Saint Thomas Aquinas over Heretics by Filippino Lippi (ca. 14571504), fresco, Basilica of Saint Mary Above Minerva, Carafa Chapel, Rome, 14891492 / De Agostini Picture Library / V. Pirozzi / Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library. The scene shows Thomas seated on a throne between personifications of Philosophy and Theology on his right and Dialectic and Grammar on his left, with the figure of vanquished Evil under his feet. In the foreground groups of the heretics refuted by Thomas in the Summa theologiae are escorted to Thomas by a papal official on our left and a Dominican on the right.

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-15426-8

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Garamond Premier Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my classmates at the North American College

Class of 1963

Ad multos annos, gloriosque annos, vivas!

CONTENTS

PREFACE

This book owes its origin to the polite persistence of Fred Appel of Princeton University Press, who kept asking me to think of contributing something to a new series, Lives of Great Religious Books. I considered composing a short book on a mystical classic, such as Bernard of Clairvauxs Sermons on the Song of Songs, but the more I thought about the possibilities the more I was drawn to the scary idea of writing a book on Thomas Aquinass Summa theologiae, one of the longest works in the canon of religious classics and one of the most studied. I am not a card-carrying member of any Thomist party and Ive written only a few things on Thomas over my academic career. Nevertheless, Ive been reading Thomas for almost sixty years and teaching him for over forty. When I was studying a dry-as-dust version of Neothomist philosophy from 1957 to 1959, I was rescued from despair by reading the works of Etienne Gilson, especially his Being and Some Philosophers. Doing theology at the Gregorian University in Rome between 1959 and 1963, I was privileged to work with two great modern investigators of Thomas, Joseph de Finance and Bernard Lonergan. It was then I realized that no matter what kind of theology one elects to pursue in life, there is no getting away from Thomas. So the opportunity to come back to Thomas and the Summa was both a challenge and a delight. Rereading the Summa and trying to catch up on at least some of the always-increasing literature on Aquinas was a homecoming. I hope the reader may be able to experience some of the intellectual stimulation I felt in what follows. I want to thank Fred Appel for valuable suggestions about shortening an originally bloated text to more manageable dimensions, and I also thank my wife, Patricia, for her customary discernment in helping with the editing process. Debbie Tegarden of Princeton University Press was unfailingly helpful in the editing process. My friends and colleagues Susan Schreiner and David Tracy gave valuable assistance with the last two chapters. Finally, three anonymous readers were also very helpful with corrections and suggestions. Any errors that remain are my own.

A Note on Citing Thomas

There is no best edition for all of Thomas Aquinas, although the Leonine Edition begun in 1880 and still under way offers a critical text for most of his writings, but not the Summa theologiae. I cite and translate the Summa from the student edition based on the Leonine text and published by the Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos in Madrid in 1955. Abbreviating the work as STh, I cite from the three parts in four sections as Ia, IaIIae, IIaIIae, and IIIa, making use of the standard divisions into question (q.) and article (a.). For example, Ia, q. 1.3 indicates the First Part, the first question, and the third article. Sometimes, for greater precision, I use corp. for the body of Thomass response, and ad 1, ad 2, and so on for his responses to the objections to his position. Other works of Thomas are cited according to standard abbreviations, a list of which can be found at the end of the book. I have included a number of endnotes to the chapters. These can easily be disregarded by readers who wish to follow the narrative without distraction, but they may be useful for those who wish to pursue aspects of Thomass thought on specific issues, especially in light of the vast literature on the Summa.

Bernard McGinn

Chicago, January 2013

INTRODUCTION

Every civilization has classic expressions. There are some cultural artifacts that come to sum up a period and a style while also becoming part of the common patrimony of human society. In European civilization Shakespeares plays not only epitomize Elizabethan England, but continue to be read around the world. The same is true of the art of Michelangelo and Leonardo, the music of Bach and Beethoven, the writings of Cervantes and Goethe. In terms of the long Middle Ages (ca. 5001500 C.E.), when Catholic Christianity was a dominant force, it is not surprising that many of the most famous cultural artifacts are religious. Disputes about which expressions of medieval culture are the most characteristic continue, but few would question that in art the medieval cathedral plays a central role, just as Dantes Divine Comedy does in literature. From the perspective of religious thought the Summa theologiae of the Dominican friar Thomas Aquinas (122574) has a unique place, in terms of both its profundity and its influence. Given its length, few have ever read the whole of the Summa. College graduates, especially students of religion and philosophy, may have studied a few selections, but somehow the Summa remains one of the few medieval works, along with Dante, known to the general public, at least in name.

Next page