1. The Technical Part of the Painters Manuals Compiled and Used by Early Iconographers. Historic Notes

The word icon comes from the Greek eikon which means image. Typically icons are devotional objects representing characters or scenes from the Bible. Throughout history they have been made on different supports, using different materials and tools.

This book presents the materials prepared and the techniques used by early iconographers of the Orthodox East. Looking at centuries-old paintings and frescoes which stood well the test of time, we marvel at the brilliance of their colors, the quality of their materials, and wonder about what these artisans knew and how they prepared their own materials and tools. What made their works stand the test of time so well (Fig. )? Coming from a time when few could read, their products, the icons, were an important teaching tool. Very little is known on the subject of the craftsmanship involved in making icons for several reasons. First, those involved in the process were members of a closed circle to which access was achieved only following a long and strenuous apprenticeship. The knowledge was passed from master to apprentice by direct demonstrations and through the information contained in the hermeneias (painters manuals) compiled by iconographers and intended exclusively for their restricted group. Due to the manner and the circumstances in which that knowledge was acquired and, even more importantly, due to the presumed qualities of the products made by iconographers, the icons, the information contained therein was considered a secret and could not be shared outside the closed circle of iconographers.

Fig. 1.1

Western external wall of the church at Monastery Voronet (Northeastern Romania), painted in the sixteenth century. Photo: M.D. Leonida

While in Western Europe these secrets ceased to be considered as such around the twelfth century, in the Orthodox East the situation stayed unchanged until much later. The iconographers of the East constituted a particular social segment in that area and it was unanimously accepted that only they could create the icon, the sacred art object considered to have a definite functionality.

The Church of the East preached and still preaches through images as well as with words. Icons were considered relays which offered to those who prayed in front of them the unique possibility of establishing a direct connection with the Transcendental [, a seen Bible, of Southeastern Europe.

Access to the iconographers guild was achieved only after a long apprenticeship concluded by a special consecration (religious) service. During that ceremony a priest (possessor of the Grace and of the power of conferring it) bestowed the divine Grace ( Grace ) upon the apprentice, brought to the ceremony by his mentor (see Chap. ].

Today, long after the painters manuals were compiled, some of the terms found therein have been forgotten or fallen out of use, which makes some parts of these manuscripts difficult to understand. We are therefore not surprised to find the opinion expressed in some older studies and books, whose authors lacked a technical background, that the recipes recommended by the hermeneias are impossible to understand and reproduce [].

In Western Europe, the first manuscripts with technical information concerning painting appeared early during Antiquity. Their authors were either painters themselves or visitors of their studios and often the information provided was accompanied by technical recommendations. The earliest manuscripts of this type marked the beginning of writing as a means to hand over the knowledge about the painters art and techniques. This change is a revolutionary one both in the means of communication and in the way secrets of painters were considered as such. Writings of Vitruvius are examples of such manuscripts.

Among the manuscripts on this topic which appeared during the early Middle Ages or later outside of Southeastern Europe we have to mention those written by Vasari].

Obviously the manuscripts we mentioned constituted exceptions for the time they were respectively authored. The general rule of the time was to limit the access to the secrets of the trade (painting) to the members of the close-knit circle of painters, the only ones having access to these manuscripts. However, this rule is not spelled out clearly anywhere. How else could we interpret Cenninis].

In the Southeastern Europe area, information and recommendations concerning the activity of iconographers appeared scattered in manuscripts of different types, not only in those dealing with art related topics. The best organized and the most complete such recommendations appear in the hermeneias , the Romanian and Greek iconographers manuals. Without knowing too well either when and where they appeared first or when the revolutionary switch from the oral transmission of the knowledge and technical tradition in the religious painting to the written one occured, we only know that they existed and that only a few of them were preserved for us.

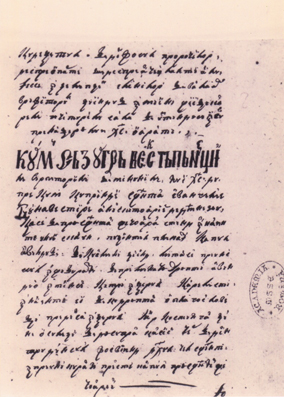

It is interesting to note that the only hermeneias known are either in Greek or in Romanian (Fig. ), languages of the two southeastern European peoples who were never integrally occupied by the Turks. All contain approximately the same type of material, organized in two big parts (a technical part and a part about iconographic matters).

Fig. 1.2

Page from a Romanian manuscript (painters manual, hermeneia ). Photo: M.D. Leonida

Here is how the sequence of the discovery of the hermeneias and of the many technical details pertaining to the hidden face of the Orthodox icon in Western Europe unfolded. In 1832, in a German journal []. The two French researchers accompanied their translation with numerous and well-documented comments, much more so than Schorn did in his paper announcing the discovery of the first such manuscript by the European West. The French translation of the first Greek hermeneia published integrally was dedicated to Victor Hugo, the well-known literary giant of that time. The enthusiasm it generated prompted the French state to cover the publishing costs of that edition.

Starting in 1845, the name hermeneia entered the language used by European scholars. It was a name used in the title of such technical-artistic manuscripts in both Greek and Romanian. Under this name they circulated through the entire area of the Orthodox East. After another decade, in 1855, the German translation of the same Greek manuscript was published. The first Greek edition had been published two years earlier, followed, three years later, by a second Greek edition. In 1868 the Russian specialist in paleography and religious art, Porfirii Uspenskii, published the Russian translation of the same manuscript [].