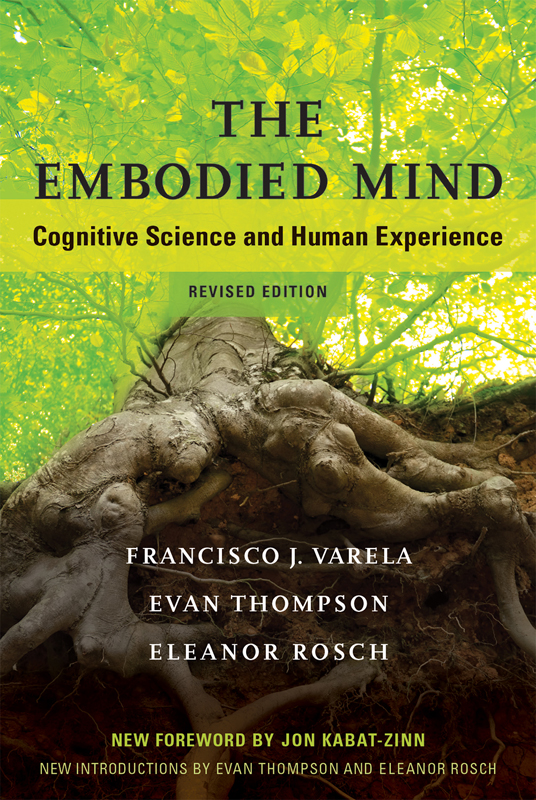

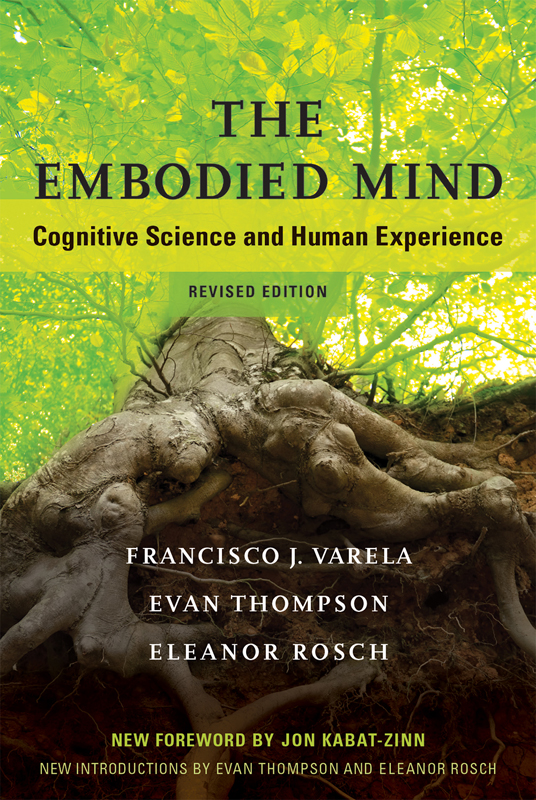

The Embodied Mind

Cognitive Science and Human Experience

revised edition

Francisco J. Varela

Evan Thompson

Eleanor Rosch

new foreword by Jon Kabat-Zinn

new introductions by Evan Thompson and Eleanor Rosch

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

1991, 2016 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

This book was set in Stone Sans and Stone Serif by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited. Printed and bound in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Varela, Francisco J., 19462001, author. | Thompson, Evan, author. | Rosch, Eleanor, author.

Title: The embodied mind : cognitive science and human experience / Francisco J. Varela, Evan Thompson, and Eleanor Rosch ; foreword by Jon Kabat-Zinn.

Description: Revised Edition. | Cambridge, MA : MIT Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016016506 | ISBN 9780262529365 (pbk. : alk. paper)

eISBN 9780262335485

Subjects: LCSH: Cognition. | Cognitive science. | Experiential learning. | Buddhist meditations.

Classification: LCC BF311 .V26 2016 | DDC 153dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016016506

ePub Version 1.0

Those who believe in substantiality are like cows;

those who believe in emptiness are worse.

Saraha (ca. ninth century CE )

Foreword to the Revised Edition

Jon Kabat-Zinn

In the annals recording the remarkable and improbable confluence of dharma, philosophy, and science in this era, if such are ever written, The Embodied Mind will be found to have played a seminal and historic role.

I was elated and, in many ways, awed when I first discovered it shortly after it was published by the MIT Press in 1991. Not that I understood it all, or even most of it, since I am neither a cognitive scientist nor a philosopher by training. But I nonetheless was able to recognize its breadth and depth, the rigor, edginess, and bravery of its scholarly lines of argument, well beyond the thought lines of academic cognitive science, and sensed that its publication by the MIT Press was a landmark and momentous signature of something new and profound emerging at the interface of science and dharma.

What I did understand of the book at the time (which over the years I wound up reading, consulting, and highlighting on multiple occasions), I found very much in alignment with my own thinking from early on in my scientific career as a molecular biologist pondering questions such as what makes life life and how consciousness arises from cells. It was also germane to my work, beginning in 1979, offering relatively intensive training in mindfulness meditation and mindful hatha yoga to medical patients with a wide range of diagnoses and chronic conditions and documenting what ensued in their lives and health from such an engagement. In those early days, I found myself at times somewhat tongue-in-cheek referring to this approachthat we later came to call MBSR, for mindfulness-based stress reductionas Buddhist meditation without the Buddhism, since mindfulness had been explicitly and authoritatively characterized as the heart of Buddhist meditation.

I remember feeling confirmed and uplifted by the centrality the authors accorded to mindfulness and mindful awareness in their wholly radical yet compelling, rigorous, and challenging attempts to bring together the fields of cognitive science, phenomenology, and dharma to examine the larger connections between mind, body, and experience. This feeling was amplified by the fact that the analysis and arguments were coming from not one but three authors, who seemed to be speaking with one voice from an unusually deep collaboration, and who were obviously also speaking from their own direct, first-personthe correctives the authors have added in their introductions to this edition to clarify a deeper understanding of mindfulness grounded in lived experience and, in particular, in relationality itself and in what they term enaction. These correctives are really evolving refinements indicative of ongoing learning and growing, and are based on continuing investigation, reflection, inquiry, dialogue among colleagues, and actual embodied and enacted cultivation/practice of mindfulness. They are themselves vital signs of health, if you will, indicators of the vitality of the evolutionary arc of thinking and praxis at the cutting edge where cognitive science and the meditative disciplines converge and radically challenge each others models and understanding. Stasis at this interface would be tantamount to attachment to and self-identification with unexamined assumptions and particular views, habits of mind that are themselves root causes of so much ignorance and suffering according to the wisdom traditions that articulated so precisely and rigorously many of the lines of inquiry pursued by the authors in the original text. So such correctives are very welcome signs of a natural generativity, learning, and humility at play herejust what one hopes for in science, in meditative practice, and in life.

At the time of the first edition and for many years afterwards, the MIT Press was headed up by the late Frank Urbanowski, a practitioner and student of Buddhist meditation himself, and a friend. Frank knew exactly what he was doing by publishing The Embodied Mind. It became the first and among the most profound and transformative of a whole family of books on cognitive science and the mind that he acquired. It was a cardinal example of what Frank termed focused disciplinary specialization, a strategy that continues to be a signature feature of the MIT Presss publishing approach to this day and that is responsible in many ways for its ongoing success. The reissuing of The Embodied Mind now, in this new edition, after almost twenty-five years, with new introductions by the surviving authors and with the original text unchanged, is evidence that the books analyses, arguments, and impact have only grown in importance and relevance over the intervening decades. Indeed, the world has become so much more receptive to mindfulness that this books republication heralds a new era in our deep collective investigation, appreciation, and possible understanding of some up-to-now fairly intractable domains: the nature of thought and emotion, the nature of what we call mind and its non-separation from body, and the nature of what we call self and its non-separation from others and from the surrounding embracing world out of which life and mind emerge.

I started graduate school at MIT in molecular biology in 1964, wanting naively and romantically to investigate the fundamental nature of life and how it relates to self and to mind. I worked on bacteria, bacteriophage, and colicins, hoping that the experience would serve as a good foundation (it did) for ultimately investigating the human mind from both the outside (the third-person perspective) and the inside (the first-person perspective). Bacteria, of course, are single-celled organisms, with an inside that is alive and a cell membrane keeping the inside intact, the outside out, and facilitating a dynamical exchange of energy and matter that keeps the inside conditions just right for life to perpetuate itself. Bacteriophage (viruses that infect bacteria with their DNA or RNA) and colicins (proteins that kill certain bacterial cells from the outside, and that are encoded by plasmids within the DNA of the source bacterium) are not alive, but they both use the life of the cell to replicate more of themselves, using different strategies. Fundamental molecular and dynamical distinctions between inside and outside, life and non-life, lie at the heart of one of Francisco Varelas many interests and contributions, namely the phenomenon of

Next page