OTHER BOOKS BY DEVADATTA KL.

In Praise of the Goddess: The Devmhtmya and Its Meaning (2003)

The Veiling Brilliance: A Journey to the Goddess (2006)

Published in 2011 by Nicolas-Hays, Inc.

P. O. Box 540206

Lake Worth, FL 33454-0206

www.nicolashays.com

Distributed to the trade by

Red Wheel/Weiser, LLC

65 Parker St. Ste. 7

Newburyport, MA 01950

www.redwheelweiser.com

Copyright 2011 by David Nelson

First Edition

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Nicolas-Hays, Inc. Reviewers may quote brief passages.

ISBN 978-0-89254-166-9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Devadatta Kali, 1944

Svetsvataropanisad : the knowledge that liberates /translation and commentary by Devadatta Kali.1st ed.

p. cm.

In English and Sanskrit (romanized); includes translation from Sanskrit.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-89254-166-0 (alk. paper)

1. Upanishads. SvetasvataropanisadCommentaries. I. Upanishads. Svetasvataropanisad. English. II. Title.

BL1124.7.S846D48 2011

294.5'9218dc22

2011009046

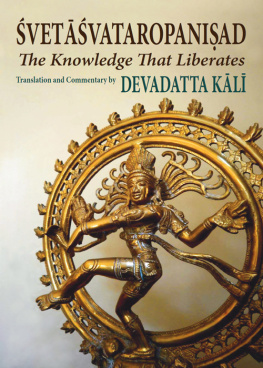

Cover and text design by David Nelson (Devadatta Kali)

Printed in the United States of America

www.redwheelweiser.com

www.redwheelweiser.com/newsletter

OTHER BOOKS BY DEVADATTA KL.

In Praise of the Goddess: The Devmhtmya and Its Meaning (2003)

The Veiling Brilliance: A Journey to the Goddess (2006)

VETVATAROPANISAD: THE KNOWLEDGE THAT LIBERATES. Copyright 2009 by David Nelson. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including but not limited to photo-copying, recording, and other information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the copyright holder, except in the case of brief quotations appearing in critical articles and reviews. For information address David Nelson, 1532 Manitou Road, Santa Barbara, CA 93105.

FIRST EDITION

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Kali, Devadatta.

vetvataropanisad: translation and commentary /

Devadatta Kali.

p. cm. 00000

ISBN 000000000

1. Upani adsHinduism. 2. HinduismUpani

adsHinduism. 2. HinduismUpani ads. 3. VedntaKashmir aivism. 4. Kashmir aivismVednta. 5. Indian PhilosophyYoga. 6. YogaIndian Philosophy.

ads. 3. VedntaKashmir aivism. 4. Kashmir aivismVednta. 5. Indian PhilosophyYoga. 6. YogaIndian Philosophy.

000000.00000 2009

000.00000000

Cover and text design by David Nelson (Devadatta Kali)

CONTENTS

PREFACE

As a newcomer to the Vedanta Society of Southern California in the autumn of 1966, I soon became acquainted with the Upani ads through an English translation by Swami Prabhavananda and Frederick Manchester. From the beginning I felt a natural compatibility with those ancient texts, and in the case of the vetvataropani

ads through an English translation by Swami Prabhavananda and Frederick Manchester. From the beginning I felt a natural compatibility with those ancient texts, and in the case of the vetvataropani ad it was a matter of love at first sight. Perhaps that response was not so unusual: in his preface Manchester had noted that in its latter half the vetvatara achieves a poetry unequaled by any other Upani

ad it was a matter of love at first sight. Perhaps that response was not so unusual: in his preface Manchester had noted that in its latter half the vetvatara achieves a poetry unequaled by any other Upani ad. In the process of translation, he recalled, it asked for wings, and the resulting flight of eloquence came about more by accident than by design. I found myself captivated by its vision of the transcendent amid a celebration of the immanent, and that impression has never faded. Four decades later this Upani

ad. In the process of translation, he recalled, it asked for wings, and the resulting flight of eloquence came about more by accident than by design. I found myself captivated by its vision of the transcendent amid a celebration of the immanent, and that impression has never faded. Four decades later this Upani ad is no less irresistible than it was on the first encounter.

ad is no less irresistible than it was on the first encounter.

About the vetvataropani

ad

Max Mller, one of the early European translators, found himself intrigued by the vetvatara's complexities and expressed no small admiration for its distinctive character. Less charitably Paul Deussen, who published a translation soon afterward, criticized the text as a mass of cleverly disguised contradictions. Another translator, Robert Ernest Hume, saw it as a battleground of conflicting doctrines, even while Indian scholars have traditionally viewed it more in terms of reconciliation or synthesis or as a statement of pure Vedantic nondualism. Despite the bewildering assessments there is no question that the vetvatara has consistently enjoyed respect as one of the most authoritative of the Upani ads. The confusion surrounding its interpretation arises from a failure to approach it on its own terms. Accordingly, the introduction to this book, Text and Context, provides the necessary religious, philosophical, and historical background for a clearer understanding of this remarkable text.

ads. The confusion surrounding its interpretation arises from a failure to approach it on its own terms. Accordingly, the introduction to this book, Text and Context, provides the necessary religious, philosophical, and historical background for a clearer understanding of this remarkable text.

About the translation

For many centuries the vetvataropani ad was passed along orally in Sanskrit from one generation to the next through a process of memorization so exacting that the transmission had nearly the fidelity of a recording. Only much later was it committed to writing. The oldest manuscripts show an occasional variation, but on the whole the teaching has come down in the original language much as the seer vetvatara configured it. For most readers today, unschooled in India's ancient literary language, acquaintance with the text will be through translation.

ad was passed along orally in Sanskrit from one generation to the next through a process of memorization so exacting that the transmission had nearly the fidelity of a recording. Only much later was it committed to writing. The oldest manuscripts show an occasional variation, but on the whole the teaching has come down in the original language much as the seer vetvatara configured it. For most readers today, unschooled in India's ancient literary language, acquaintance with the text will be through translation.

To translate literally means to carry across, and in the broadest sense it entails more than converting an utterance from one language to another. Whenever we communicate through the spoken or written word, even if the exchange takes place through a single common language, we engage in an act of carrying information or ideas across a divide. The purpose of linguistic interaction is to convey information from one mind to another, and with that sharing of information, the question of individual differences and other variables arises. What the speaker or writer intends is not necessarily what the listener or reader will understand. Each participant in the exchange draws on a unique store of experience either in expressing something or in interpreting it, and there is no guarantee that it will come across as intended. Even when two people converse face to face with the additional nuances of tone, mood, rhythm, volume, emphasis, or gesture to reinforce the message, the spoken word may be open to interpretation. On the printed page, without those additional signals, the latitude for interpretation becomes even wider.

Additional layers of complication arise when the message has to be put into another language. Ideally, in carrying meaning across linguistic boundaries, a translation should assure as safe a passage as is humanly possible. The journey can be fraught with difficulty, because each language embodies its own world-view, conditioned by place, time, and culture. The divide can be small and the crossing easy if two languages are closely related; it can be great and fraught with hazard if they are not related at all. In the case of Sanskrit and English the two languages are distantly related and separated by half a world and thousands of years. They speak for very distinct cultures. It is reasonable to ask if the message of the Upani

Next page

adsHinduism. 2. HinduismUpani

adsHinduism. 2. HinduismUpani