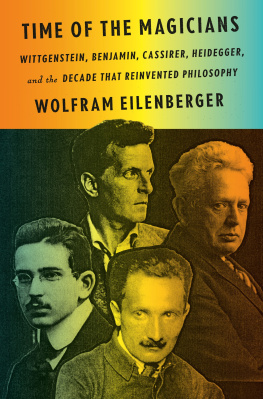

ERNST CASSIRER

ERNST

CASSIRER

THE LAST PHILOSOPHER OF CULTURE

EDWARD SKIDELSKY

Copyright 2008 by Princeton University Press

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should

be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Second printing, and first paperback printing, 2012

Paperback ISBN 978-0-691-15235-6

The Library of Congress has cataloged the cloth edition

of this book as follows

Skidelsky, Edward.

Ernst Cassirer : the last philosopher of culture / Edward Skidelsky.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-13134-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Cassirer, Ernst, 18741945. I. Title.

B3216.C34S55 2009

193dc22

2008007127

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Goudy

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

To Gus and Robert

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book grew out of a doctoral thesis I wrote at the University of Oxford. I owe a great debt of gratitude to Larry Siedentop, who first suggested the idea of writing on Ernst Cassirer; to my supervisors Michael Rosen and Jan-Werner Mller, encouraging and supportive throughout; and to my examiners John Burrow and Martin Ruehl, whose comments forced me to rethink some of my basic arguments. I would especially like to thank John Michael Krois, at the Humboldt University, Berlin, whose generosity in helping me navigate the ocean of Cassirers unpublished papers was all the greater for the fact that we disagreed on many points of interpretation. His benign impartiality does Cassirer proud.

Paul Bishop, Joshua Cherniss, Dina Gusejnova, Barbara Naumann, Anders Nes, Wu Junqing, and my father, Robert, kindly read and commented on different parts of this book. My friends Marco Haase, Benjamin and Christiane Lahusen, and Anna Schuchart all displayed saintly patience with my stuttering German. Birgit Recki, Pankaj Mishra, Davide Cargnello, and Jacquelyn Fernholz helped me locate references. Dorothea McEwan and Claudia Wedepohl, archivists at the Warburg Institute, came to my aid when the handwriting of Cassirer and Aby Warburg proved impenetrable. The Arts and Humanities Research Board and the Deutsche Akademische Austausch Dienst provided me with the support without which this book could not have been written.

Above all, I am grateful to my parents, Gus and Robert, who never lost faith in this project, or at least were so kind as to conceal their doubts. This book is dedicated to them.

ERNST CASSIRER

INTRODUCTION

On April 23, 1929, in the famous Swiss resort of Davos, two of the leading philosophers of the day met in debate. On the one side was Ernst Cassirer, distinguished representative of the German idealist tradition and champion of the Weimar Republic. On the other was Martin Heidegger, the younger man, whose recently published Being and Time had shaken the idealist tradition to its foundations, and whose politics, though still uncertain, were plainly far from liberal. It was a symbolic moment. The old was pitted against the new, the humanism of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries against the radicalism of the twentieth. All agreed that Heidegger, not Cassirer, was the man of the future. No one realized just what that future held in store.

After the debate, some of the attendants staged a humorous reenactment. The part of Heidegger was taken by one of his students, Hans Bollnow, who parodied his teachers etymologies with lines such as to interpret is to stand a thing on its head. But the real satire was reserved for Cassirer, played by none other than the young Emmanuel Levinas. His hair covered in white powder, intoning I am a pacifist and Humboldt, culture, Humboldt, culture, the future matres-a-penser cut a sorry figure of decrepitude and defeat. Thus expired the once glorious tradition of German humanism.

Humboldt, culture, Humboldt, culture. What exactly did Levinas mean by those words? Humboldt referred to Wilhelm von Humboldt, philosopher, statesman, and pioneer of the modern university. Culture referred to his spiritual ideal. Together, the two words stood for the conviction, shared by most educated nineteenth-century Germans, that self-realization, not self-sacrifice, is the goal of life, and that we realize ourselves not by retiring from the broader

Humboldts ideal gradually came unstuck over the course of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Problems arose in two quarters. Natural science had always been a thorn in the flesh of culture. With its exact method and formulaic language, it was in no obvious sense an expression of the human spirit. Goethe himself had fulminated against the narrow dogmatism of the Newtonians. By the end of the nineteenth century, science had swollen into a monstrous leviathan, possessed of a voracious colonizing energy. Its high priests, the positivists, proclaimed in strident tones that it needed no moral or metaphysical sanction, that it was itself the final arbiter of true and false. Science was no longer a branch of culture; on the contrary, culture had to justify itself before science.

Humboldts ideal of culture also came under fire from a quite different angle. Faced with the alienating structures of science and its offshoot, the modern factory system, a few bold spirits sought salvation in the depths of the psyche. Here, in the Dionysian, the id, they found that magic that had vanished from the objective world. This was a radically new departure. Humboldt and his contemporaries had by no means ignored the passions, but had viewed them as essentially subservient to the shaping forces of culture. Nietzsche and his successors saw them as wild and unruly. Humboldt had insisted on the harmony of the faculties; these latter discerned a tragic gulf between reason and passion, logos and mythos. In place of self-realization, man was now confronted with rival forms of self-surrenderto the superpersonal forces of science and technology, or to the subpersonal forces of intoxication and desire. He was torn, so to speak, both upward and downward.

But there was one section of German society that preserved better than most Humboldts ideal of culture. Cut off from their own religious traditions, yet denied full participation in civic life, assimilated German Jews embraced their host nations philosophy, literature, and music with a fervor rooted in anxiety. It was into one such wealthy and cultured family that on July 28, 1874, Cassirer was born. His cousins included the publisher Bruno Cassirer, the art collector Paul Cassirer, and the pioneering Gestalt psychologist Kurt Goldstein. This was a world intimately acquainted with philosophy, art, and science, only superficially with religion, and not at all with politics. Levinass satire was spot on target. Cassirers philosophy was indeed an attempta characteristically Jewish attemptto preserve the liberal ideal of culture under increasingly hostile conditions. It was a rearguard action on behalf of a vanishing civilization.

Cassirers first interest was science. Between the years 1899 and 1910, as the leading young representative of the so-called Marburg school of neo-Kantianism, he wrote a series of epochal works on the history and theory of physics, mathematics, and logic. His aim was to uphold, against the onslaughts of positivism, a broadly Kantian conception of science as an expression of the creativity of human reason. Cassirer later extended a similar approach to Einsteins theory of relativity and quantum physics. It was a losing battle. The recent revolutions in mathematics, logic, and physics were more commonly interpreted as proof

Next page