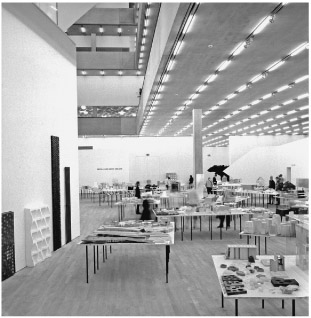

Model-making has been a central aspect in the work of the Swiss architectural practice Herzog & de Meuron since its beginnings, as illustrated by the prominence of physical models in several exhibitions of their oeuvre, for example the ones held in the Paris Centre Pompidou (1995), in the Milan Prada Foundation (2001), or in the Schaulager Museum in Basel (2004) ( The reasons for their important use of architectural models are certainly multifaceted and complex, and, following a subjective reading, one could suggest a relation between this working tool and movement, namely, the way the architects imagine and foresee people approaching and accessing, moving into and through their buildings. In this sense, the numerous models built by the Swiss firm would illustrate, among other things, the architects concern with people moving around their buildings admittedly a concern that should constitute a central aspect of each architectural project. However, this concern, together with the production of physical models, seems to be suffering a decline, in a time characterised by mainly virtual representation of architecture. This chapter aims to shed some light on Herzog & de Meurons exemplary use of physical models, while also constituting a plaidoyer for this working tool and its crucial role in the projection of movement.

The Parisian exhibition was conceived by the artist Rmy Zaugg in collaboration with the architects, as shown by a fax sent to the artist by Jacques Herzog on 25 November 1994.

After some exhibitions held at the Peter Blum Gallery in New York (1997) and the Tate Modern in London (2000), among others, the architects again exhibited a part of their oeuvre in the Milan Prada Foundation.

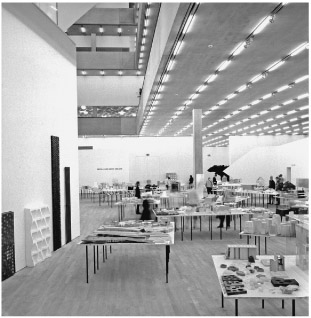

Herzog & de Meuron: No. 250, An Exhibition, Schaulager Museum, Basel, Switzerland (2004). Tables exhibiting models, mock-ups and samples

Source: Photograph by Margherita Spiluttini

It becomes evident that, in their exhibitions, the architects show an important number of models as three-dimensional working documents, and two questions arise from this observation: first, can the exhibitions be understood as representing Herzog & de Meurons oeuvre in its architectural approach? Second, what is the reason for this keen interest in model-making? Concerning the first, Herzog confirmed, in a conversation with Zaugg: For us, an architectural exhibition must be essentially based on a strong conception, at the same time precise and reflective, which presents and underlines the working method. As the architect reports, an architectural exhibition should represent the working method applied, and, therefore, the abovementioned examples may be understood as representative, not only of their architectural approach, but also of their interest in models as tools and working documents. The reasons that lead to models taking on a central role in the architects oeuvre are, however, multifaceted and more complex. First of all, it is relevant to underline that Herzog & de Meuron understand the architectural models, not only as mere tools of representation, but also as an integral part of architecture or the built reality, as they explain:

In this sense, models explain underlying concepts of the buildings they represent and, at the same time, they permit the experience of their physical, material presence. Yet, following an admittedly more subjective reading of their model-making, one can suggest a relation between the latter and the projection of movement: the numerous models produced by the office certainly help anticipate movement, by individuals, around and into the building. On this note, one should recall that physical models, by means of their three-dimensional nature, enable the perception of depth by architects, with their binocular vision. Furthermore, as objects, physical models also allow people to navigate around them, to take different points of view; in other words, they allow the architect to create a sequence of views, rather than one static view. Taking these characteristics of physical models into consideration, their important role in anticipating movement in and around a building becomes quite obvious.

A closer look at three, more or less recent, buildings by Herzog & de Meuron helps illustrate the central role of models in the understanding of their work, but also the relation here established between these models and the anticipation of movement. The library at Cottbus Technical University, a project represented at the Tate Modern and Schaulager exhibitions, was developed and built between 1994 and 2004. These notes, together with the red arrows marked in this sketch, confirm that movement around and access into the building were main concerns in this project and, moreover, were actually a form-defining aspect. However, if the sketch confirms the architects concern, the many volumetric models built for this project were also likely to have been a helpful crutch in the design process.

Herzog & de Meuron describe the Prada store built in Tokyo as an extremely visual, sculptural shape, but also a very simple and immediately recognizable one. Through this move, the architects created a more generous entry to the building, some leeway in the dense neighbourhood of downtown Tokyo. Moreover, through this move, tested in the models mentioned, the architects influenced the way individuals move towards, around and into the building: upon visiting the Prada store, one first enters the plaza, possibly pausing on one of its benches, and then one walks across and into the building through the main entrance, placed on the lateral faade.

Herzog & de Meuron: VitraHaus, Vitra Campus, Weil am Rhein, Germany (20069). Working models illustrating a promenade through the building

Source: Photograph 2013, Herzog & de Meuron Basel

If, for the Cottbus Library and the Prada Store, the relation established between the models and the anticipation of movement focused mainly on movement around, and access into, the building, the VitraHaus invites one to develop the argument further, or, more precisely, to the projection of the promenade inside the building, again by help of working models. The VitraHaus was developed and built between 2006 and 2009 for the furniture firm Vitra at their campus in Weil am Rhein, in the south-west part of Germany.). For the development and verification of this promenade through the building, the model is an ineluctable tool, and this for different reasons: first, it would be difficult to represent the stacking of volumes by a mere floor plan. Different colours or tones of grey could eventually explain this matter; however, a physical model is more efficient in the expression of depth through the binocular view of the architect. Further, the model also helps to illustrate the different points of connection between the volumes, and their verification from different points of view. In the case of the VitraHaus, these connection points are crucial, as they contain stairs and elevators and, in this sense, enable a continuous promenade through the building.

The question of the working model in the oeuvre of Herzog & de Meuron has elsewhere been further developed, and the examples illustrated here may only serve as a starting point for broader and more extensive reflections on models as tools to anticipate movement. With the observations shared, this chapter seeks to invite the youngest, digital generation of architects not to underestimate but hopefully to re-evaluate the model as an admittedly basic, yet effective working tool.