POSTMODERN HOLLYWOOD

WHATS NEW IN FILM AND

WHY IT MAKES US FEEL

SO STRANGE

M. KeithBooker

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Booker, M. Keith.

Postmodern Hollywood : what's new in film and why it makes us feelso strange / M. Keith Booker. p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13:978-0-275-99900-1 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-275-99900-9

1. Motion picturesPhilosophy. 2. PostmodernismSocial aspects. I.Title. PN1995.B613 2007

791.430973'090511dc22 2007023400

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available.

Copyright 2007 by M. Keith Booker

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, byany process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2007023400

ISBN-13: 978-0-275-99900-1 ISBN-10: 0-275-99900-9

First published in 2007

Praeger Publishers, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 Animprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.praeger.com

Printed in the United States of America

The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent PaperStandard issued by the National Information Standards Organization(Z39.48-1984).

10 987654321

For Amy, Adam, Marcus, Dakota, Skylor, and Benjamin

Contents

Introduction: Postmodernism and PopularFilm

Postmodernism, as both a historical and a cultural phenomenon, hasbeen a central topic of academic discussions of culture and history in the pastfew decades. Partly because of the sometimes arcane nature of thesediscussions, the phenomenon of postmodernism has gained a reputation forcomplexity and inaccessibility, and it is certainly the case that some elementsof postmodern thought, because they run counter to the dictates of what hascome to be regarded as ''common sense,'' are a bit difficult for the ordinaryperson to grasp. It is also the case that the specific films used by academiccritics to illustrate the phenomenon of postmodernism in film have sometimesbeen difficult and abstruse, though most theories of postmodernism suggest thatit is a far-reaching phenomenon that should have an impact on virtually everyarea of contemporary cultural production.

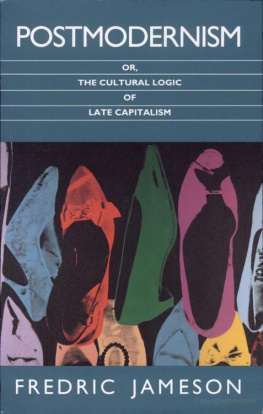

For example, the films of David Lynch, widely regarded as adirector of confusing ''art films,'' have been front and center in academicdiscussions of postmodern film. Thus, Lynch's Blue Velvet (1986) is oneof the principal films discussed by Fredric Jameson as exemplary culturalproducts of the postmodern era in his seminal work Postmodernism; or, TheCultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1991). Blue Velvet is also aprimary example cited by Norman Denzin in Images of Postmodern Society,his sociological discussion of the postmodern cultural terrain. Denzin notes inparticular the film's refusal to identify its historical setting, freely mixingimages that appear to derive from different historical periods: ''This is afilm which evokes, mocks, yet lends quasi-reverence for the icons of the past,while it places them in the present'' (469). In addition, this film repeatedlystates its central message (''It's a strange world'') almost like a mantra, butthis message is entirely trite, suggesting that Lynch is more interested increating artistic images than in any sort of critical engagement withreal-world issues. The catchphrase ''It's a strange world'' may go a long waytoward explaining the tendency toward strangeness in Lynch's films, and therebysimply becomes mimetic.

Blue Velvet departs from Hollywood convention in a numberof ways, but it is not really an inaccessible film. In it, teenage protagonists(played by Kyle MacLachlan and Laura Dern) discover their sexuality in theirbudding mutual passion, at the same time making the parallel discovery that theseemingly idyllic life of their town of Lumberton is underwritten by a darkworld of crime and perversion that lies just beneath that placid surface. Thisis a film that openly invites Freudian readingsso much so that any suchreadings would be superfluous.

However, what Lynch's films represent is emphatically not realitybut other representations of realitywhich explains why they are sometimes soconfusing to viewers who attempt to interpret them as being ''about'' the realworld. Thus, the superficial tranquility of Lumberton with its bloomingflowers, singing birds, white picket fences, and friendly firemenis quitetransparently derived from nostalgic cliches of the American 1950s, with a lookreminiscent more of a Disneyesque version of a town than any real town thatever existed in the 1950s or any other time. Meanwhile, the dark underside ofLumberton society seems equally stereotypical, deriving its material and look(cozy suburban homes suddenly replaced by stark urban red-brick buildings) fromfilm noiror what film noir might have been like without the Production Code.There are, actually, hints that the dark side of Lumberton might be a bit moreauthentic than the beautiful side, primarily in the way Lynch employs remindersof the tooth-and-claw nature of life in the animal kingdom, which, likeLumberton, can be both beautiful and violentas signaled by the film's finalimage of a robin that lands on a window sill announcing the town's return totranquility, but is at the same time eating an insect it has captured.

As noted by Denzin, Blue Velvet includes a number ofinconsistent historical markers, though its principal historical roots liebetween the mid-1980s, when the film was made, and the 1950s, from whence manyof the characters seem to emerge and for which the film shows a certainnostalgia (another key tendency of postmodern culture), though quite vaguelydefined. The 1950s are never overtly identified as an object of nostalgia,while much of the logic of the film seems specifically meant to undermine thekinds of idealized visions of small-town, nuclear-family life that are moretypically associated with wistful visions of the 1950s. Much the same sort ofhazy nostalgia informs Twin Peaks, the 19901991 television series inwhich Lynch was centrally involved, as it does Lynch's recent filmMulholland Drive (2001).1 Indeed, the nostalgia of MulhollandDrive might be seen as especially postmodern in that the setting of thefilm is quite clearly contemporary with its making, yet its atmosphere andvisual style show the clear influence of the noir films of the 1950s while italso draws upon a panoply of motifs from older films for its plot andcharacterization.

If postmodern films such as Blue Velvet and MulhollandDrive can, in fact, be understood by fairly broad audiences if approachedproperly, it is also the case that many extremely popular (and seemingly veryaccessible) films also epitomize the characteristics associated by critics suchas Jameson and Denzin with postmodernism. Tim Burton's Charlie and theChocolate Factory (2005), for example, is widely regarded as a children'sfilm. It is, after all, a remake of a classic children's film, Willy Wonkaand the Chocolate Factory (1971). But Charlie and the Chocolate Factoryis far more than a children's entertainment. For one thing, it is a gorgeousfilm, filled with treats for the eyes and ears that are every bit as sweet asthe confections whipped up in the factory of the title. It is also an exemplarypostmodern film, both because of its emphasis on spectacular images and becauseof a playful tone underwritten by darkness. Among other things, the hints of darknessmake the spirit of the film much closer to that of the source material in RoaldDahl's novel of the same title than was the original 1971 film adaptation. Butall of Burton's films tend to contain dark elements, and Charlie and theChocolate Factory is quintessential Burton, even if the previous works ofDahl and director Mel Stuart provided the basic materials with which he worked.In particular, the film epitomizes Burton's trademark focus on visual imageryover plot and characterization. In this case, of course, the production ofimpressive images is aided by the film's ultrahigh budget, though in many waysthe film resembles nothing more than

Next page