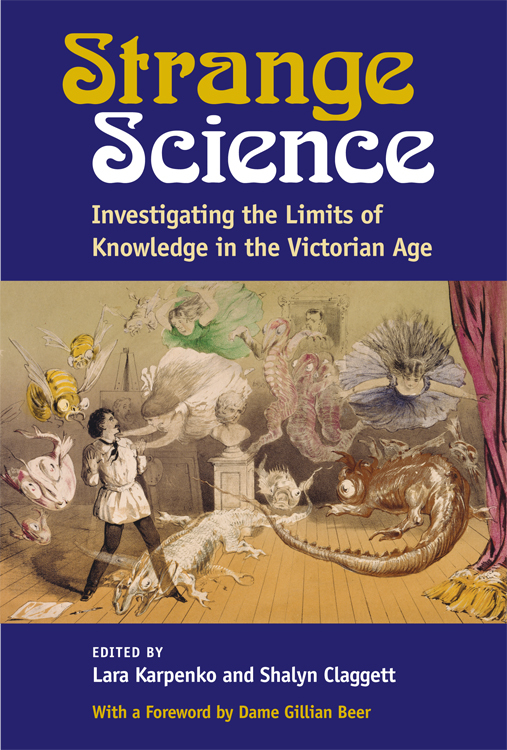

Lara Karpenko - Strange Science: Investigating the Limits of Knowledge in the Victorian Age

Here you can read online Lara Karpenko - Strange Science: Investigating the Limits of Knowledge in the Victorian Age full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2018, publisher: University of Michigan, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Strange Science: Investigating the Limits of Knowledge in the Victorian Age

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Michigan

- Genre:

- Year:2018

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Strange Science: Investigating the Limits of Knowledge in the Victorian Age: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Strange Science: Investigating the Limits of Knowledge in the Victorian Age" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Lara Karpenko: author's other books

Who wrote Strange Science: Investigating the Limits of Knowledge in the Victorian Age? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Strange Science: Investigating the Limits of Knowledge in the Victorian Age — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Strange Science: Investigating the Limits of Knowledge in the Victorian Age" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Page i

Page i Lara Karpenko and Shalyn Claggett editors

University of Michigan Press

Ann Arbor

Copyright 2017 by Lara Karpenko and Shalyn Claggett

All rights reserved

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher.

Published in the United States of America by the

University of Michigan Press

Manufactured in the United States of America

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Karpenko, Lara Pauline, editor. | Claggett, Shalyn R., editor.

Title: Strange science : investigating the limits of knowledge in the Victorian Age / Lara Karpenko and Shalyn Claggett, editors.

Description: Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016035928| ISBN 9780472130177 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780472122455 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: ScienceSocial aspectsGreat BritainHistory19th century. | ScienceGreat BritainHistory19th century. | Great BritainHistoryVictoria, 18371901. | ParapsychologyGreat BritainHistory19th century.

Classification: LCC Q127.G5 S77 2017 | DDC 509.41/09034dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016035928

- Dame Gillian Beer

- Lara Karpenko and Shalyn Claggett

- Lynn Voskuil

- Meegan Kennedy

- Narin Hassan

- Elizabeth Chang

- Danielle Coriale

- James Emmott

- Lara Karpenko

- Suzanne Raitt

- Barri J. Gold

- Sumangala Bhattacharya

- Anna Maria Jones

- L. Anne Delgado

- Tamara Ketabgian

Dame Gillian Beer

In this volume, Strange Science, the editors Lara Karpenko and Shalyn Claggett emphasize the borders of investigation in their subtitle, Investigating the Limits of Knowledge in the Victorian Age. Limits here are subjects for fresh investigation rather than clamping containers. Beyond the current limits are thriving new territories, or delusive dream countries. This powerful collection gathers examples of both. But a number of the essays also make it clear that even work that fails or where the procedures are chaotic and the assumptions doubtful may eventually find some presence in later discoveries. Work that challenges dominant assumptions may provoke different kinds of insight from more orthodox workers over time.

Science is preoccupied with discovery and with justification. To that degree, all science seeks the strange. When found, the aim is to find a place for the discovery within the known system or, more radically and more rarely, to change the system. The struggle between novelty and affirmation of the known gives the zest to much scientific work. It demands cautious procedures and audacious guesses at the same time. Innovation and repetition are both essential. That much can be said of scientific work across fields and across time. But there are major differences between the practices of knowledge-seekers in the nineteenth century and the present day. One difference is the emphasis then on individual investigation rather than teamwork and the somewhat belated Page viii arrival later in the century of university laboratories with an array of instrumentation.

The essays here are concentrated in Britain so that the research cultures described are those of people in Victorias reign, living within arguments and assumptions about empire, gender, and class that mayor may notbe unfamiliar now. Most of the people discussed in this book could assume a postal system that in London made deliveries at least ten times a day; they took for granted prodigious letter writing and intricate face-to-face contacts within social groups. Even within this kingdom diverse methods and enquiries were being pursued. The sheer variety of research cultures in different parts of the British Isles during the nineteenth century has been explored in the collection of essays edited by David N. Livingstone and W. J. Withers, Geographies of Nineteenth-Century Science.

Empire produced some hierarchical delusions but it also propelled British people across the world and gave many an intimate familiarity with places remote from these islands. The passion for collecting, whether birds eggs or butterflies, stones or big game, seems to have been unhampered by qualms about its effects. It ravaged some species; it also allowed an exquisite awareness of minute differences from example to example. It fueled taxonomic sophistication and it gratified the urge to possess, which is always a tempered or intemperate element in knowledge-gathering. The rich array of general journals, many of which discussed scientific matters alongside political, literary, and local issues, meant that the sciences were present in ordinary conversation among the educated. Geoffrey Cantor and Sally Shuttleworth demonstrated that in their edited collection Science Serialized: Representations of the Sciences in Nineteenth-Century Periodicals and in their website Science in the Nineteenth-Century Periodical. Shuttleworth is now leading a major investigation, Constructing Scientific Communities: Citizen Science in the Nineteenth and Twenty-first Centuries, which is producing fresh knowledge about the contribution of amateurs to scientific projects in the Victorian era as well as in our own. There is room for much more work on the contributions of Victorian working people to scientific knowledge-gathering.

How, then, to distinguish between scientific work familiar and strange, orthodox and odd? As the collection of essays makes clear, some enquiries that may now seem strange were, for a time at least, accepted as potentially mainstream science. The most famous of these is spiritualism, with the careful, even skeptical, evidence-gathering of the British Society for Psychical Research drawing in important scientists such as Page ix the distinguished chemist and physicist Sir William Crookes. The Societys Phantasms of the Living, as L. Anne Delgado comments, shows the unsteady nature of both human perception and the knowledge that perception itself produces. Nevertheless, their use of witness statements chimes with current interest in individual accounts of phenomena, and their concern with perceptual bias even connects forward to some of the preoccupations of neuroscience now. And mesmerism, as Karpenkos essay suggests, has never gone away.

Strange science has a way of leaving traces for later workers to pursue. As Barri Gold points out, the continuity between traditional and more exotic theories relies on the principle... that what we learn or hypothesize about the natural world must be consistent with what we already know, which constrains and shapes any paradigm shift within the sciences. Yet what we know about the natural world is itself shifting; indeed, exploring and opening up those shifts is a fundamental and central concern of scientific enquiry. It becomes clear that no easy and permanent boundaries exist between the sober known and the extreme imagination. W. K. Clifford, whose geometric Clifford algebras now underpin many advances in physics and computing (though they were beyond the capacity of most of his contemporaries), asked his contemporaries in the 1870s to question even the uniformity of nature and to be skeptical of induction since there may always be another case not yet known or encompassed by the definitive current laws. Clifford was married to the novelist Lucy Lane Clifford and himself enjoyed writing fairy stories. His central demand was for the constant testing of belief by evidence. This demand does not exclude imagination. Like John Tyndall, another foresighted thinker whose work is alluded to in a number of the essays here, Clifford emphasizes the uses of imagining. He writes: The scientific discovery appears first as the hypothesis of an analogy; and science tends to become independent of the hypothesis. Before science can detach itself from the hypothetical, it must work through guesses and analogy. Though hypothesis may be superseded, analogy persists as a tool for understanding similarities, and for measuring differences.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Strange Science: Investigating the Limits of Knowledge in the Victorian Age»

Look at similar books to Strange Science: Investigating the Limits of Knowledge in the Victorian Age. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Strange Science: Investigating the Limits of Knowledge in the Victorian Age and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.