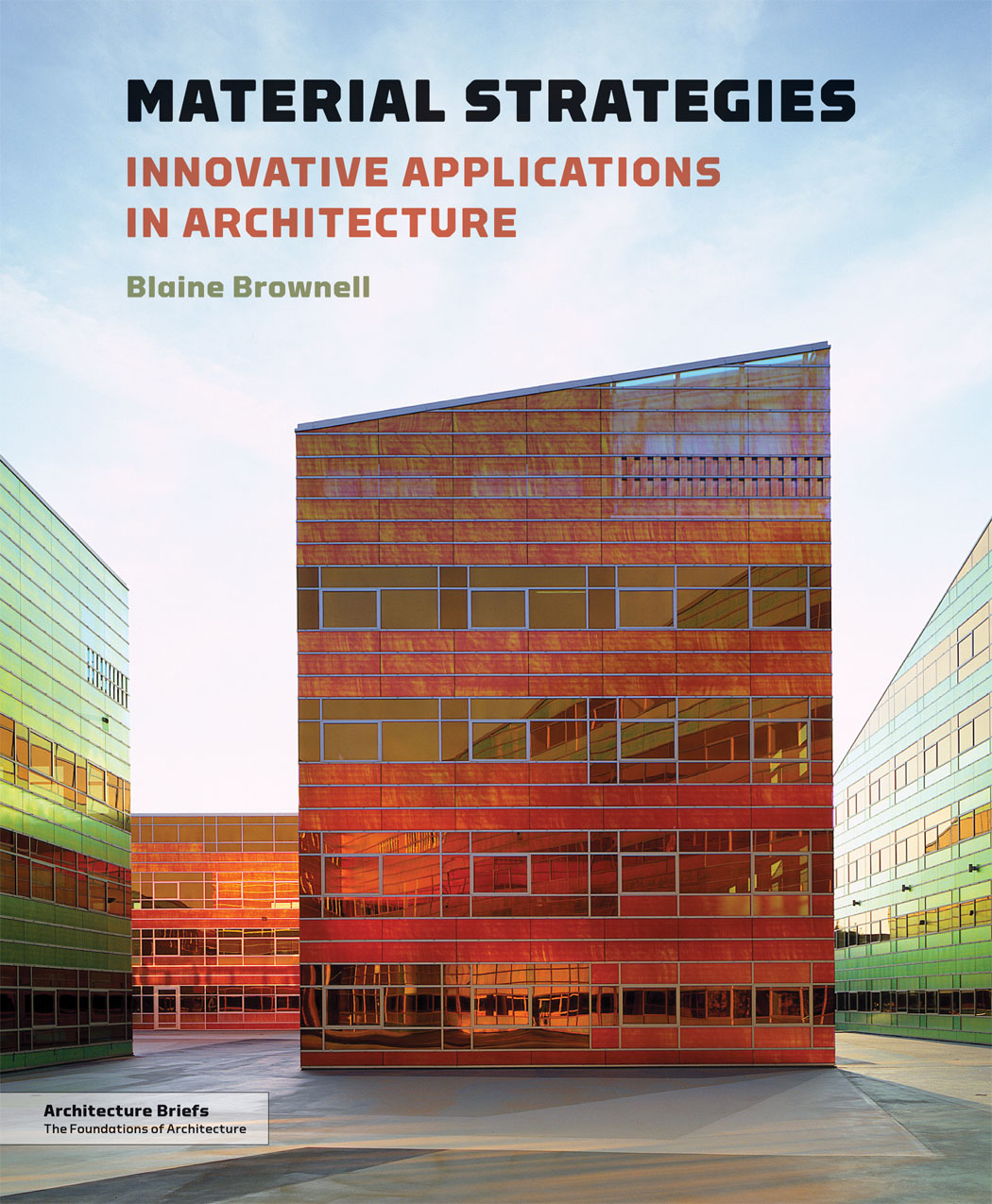

Material Strategies

Also in the Architecture Brief series:

Architects Draw

Sue Ferguson Gussow

ISBN 978-1-56898-740-8

Architectural Lighting: Designing with Light and Space

Herve Descottes, Cecilia E. Ramos

ISBN 978-1-56898-938-9

Architectural Photography the Digital Way

Gerry Kopelow

ISBN 978-1-56898-697-5

Building Envelopes: An Integrated Approach

Jenny Lovell

ISBN 978-1-56898-818-4

Digital Fabrications: Architectural and Material Techniques

Lisa Iwamoto

ISBN 978-1-56898-790-3

Ethics for Architects: 50 Dilemmas of Professional Practice

Thomas Fisher

ISBN 978-1-56898-946-4

Model Making

Megan Werner

ISBN 978-1-56898-870-2

Old Buildings, New Designs: Architectural Transformations

Charles Bloszies

ISBN 978-1-61689-035-3

Philosophy for Architects

Branko Mitrovi

ISBN 978-1-56898-994-5

To Nancie and Michael Warner, my first teachers of art and building.

Published by

Princeton Architectural Press

37 East 7th Street

New York, NY 10003

Visit our website at www.papress.com

2012 Princeton Architectural Press

All rights reserved

15 14 13 12 4 3 2 1 First edition

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written

permission from the publisher, except in the context of reviews.

Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright.

Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions.

Editor: Linda Lee

Designer: Paul Wagner

Special thanks to: Bree Anne Apperley, Sara Bader, Nicola Bednarek Brower,

Janet Behning, Fannie Bushin, Megan Carey, Carina Cha, Tom Cho, Russell Fernandez,

Jan Haux, Felipe Hoyos, Jennifer Lippert, Gina Morrow, John Myers, Katharine Myers,

Margaret Rogalski, Dan Simon, Andrew Stepanian, Joseph Weston, and Deb Wood

of Princeton Architectural Press Kevin C. Lippert, publisher

Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Brownell, Blaine, 1970

Material strategies : innovative applications in architecture /

Blaine Brownell. 1st ed.

p. cm. (Architecture briefs)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-56898-986-0 (alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-61689-189-3 (Digital)

1. Building materialsTechnological innovations. 2. Architecture

Technological innovationsCase studies. I. Title.

TA403.6.B76 2012

721.04dc23

2011019044

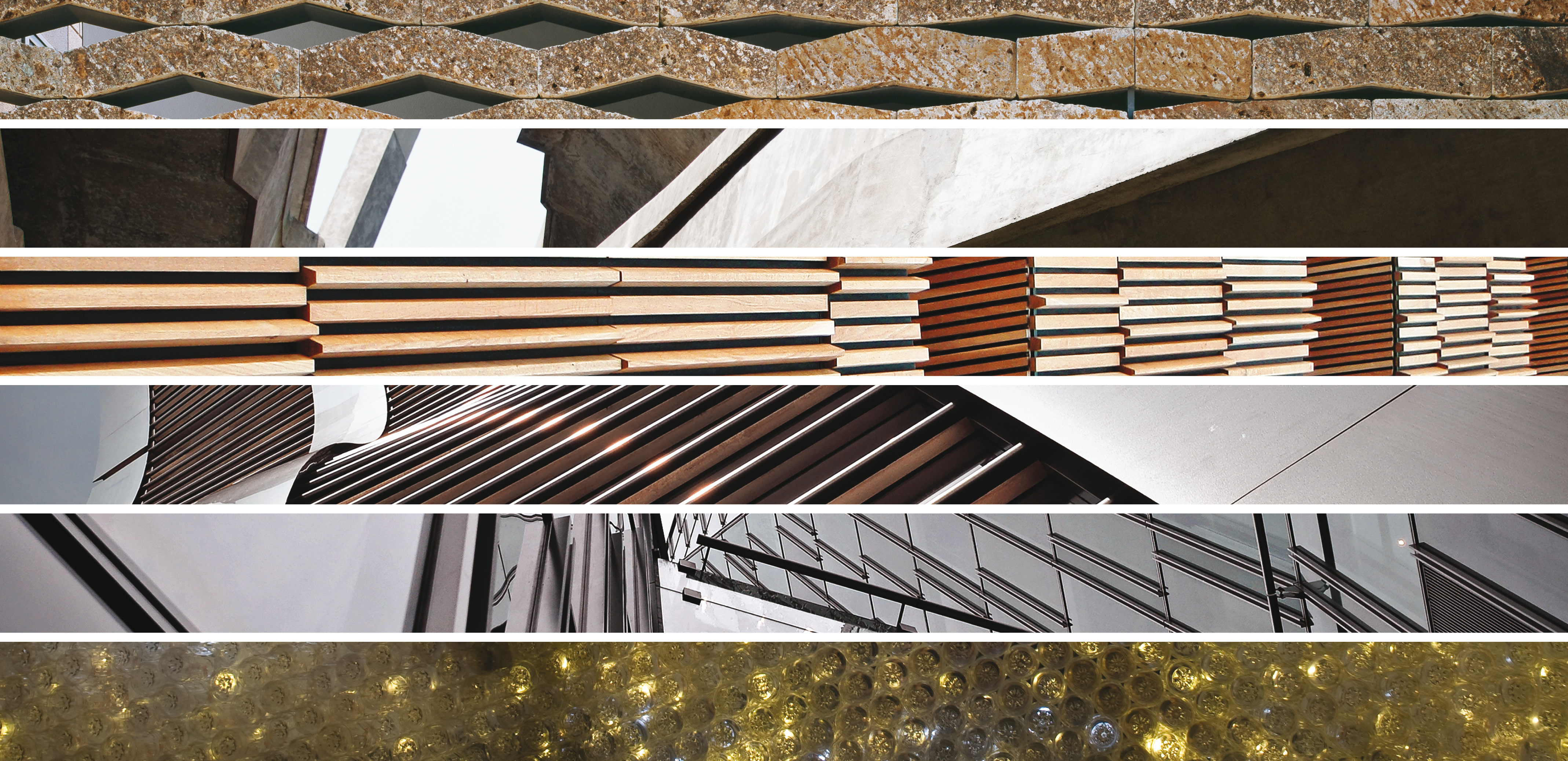

Architecture is born out of the shrewd alignment of concept and matter. The product of what Louis Kahn termed the measurable and the unmeasurable, architecture is the fulfillment of a spatial premise by way of material substance. Throughout history architecture has been shaped by the continual transformation of material technologies and application methods. Its course of development is inseparable from the shifting terrain of technology and the social effects that result. This intrinsic alignment with changewhether from a welcomed or critical perspectivereveals the extent to which architecture is inherently tied to material innovation.

In his assessment of canonical twentieth-century works of architecture, historian Richard Weston states that the bias has been toward those [buildings] that were innovativestylistically, technically, or programmaticallyand especially those that significantly affected the course of architecture. On one hand, new products and processes have transformed architecture by enabling alternative construction techniques and novel spatial possibilities. On the other hand, the architects utilization of materials in unexpected ways has demonstrated architectures capacity to inspire new growth in construction-related industries as well as stimulate cultural change. Both tendencies demonstrate the extent to which the innovative application of materials has been vital to the advancement of architecture.

Motivations

Innovation is motivated by a variety of factors. The recognition of an acute economic, social or environmental need can spur novel solutions, as seen in the development of the skyscraper in land-starved cities in the 1880s, modern social housing during the 1920s urban expansion, or superinsulated buildings during the 1970s oil crisis. The expansion of new technologies beyond their original fields can also spark innovation, such as materials developed for military or aerospace uses that find their way to the consumer marketplace.

Presently, the world faces a series of fundamental challenges that define a new context for architecture. The scale and pace of environmental, technological, and social change today is remarkable. Population growth and accelerating urban migrations outpace the replenishment capacity of the earths resources. Global warming, desertification, and eutrophication portend ominous climate transformations. At the same time, the rate and number of new technologies have recently exploded. Vastly more new products are available for architecture than in the previous history of building construction, and the rapid deployment of low-cost communication and computer technologies has enabled increasing populations to participate in a broader global conversation, propagating the visual potency and cultural-shaping capacity of design. The result of these changes presents an unrivaled set of complexities for architects as well as opportunities in architecture, whichsince buildings consume nearly half of all energy and resourceswill inevitably evolve accordingly.

It is not sufficient for architecture to respond to this new environmental, technological, and social context with modest, shortsighted changes. Anticipating our current situation, Buckminster Fuller proposed a concept he called the world game, which claims that a global population with access to sophisticated technologies and robust data about world resources and their distribution would make beneficial choices for humanity as well as the environment.

In order to fulfill this goal, architects must replace status-quo thinking with enlightened proposals for alternative methods and manifestations of design. Supporting the idea that shifting ones expectations exposes the limitations of traditional practices and environments, media scholar Marshall McLuhan championed the transformation of the environment itself into a work of art.

The Knowledge Gap

Despite the broadly appreciated need to transcend convention, specific methodologies for achieving material innovation in design are rarely taught in academia or practice. In architectural curricula, material education typically occurs within a building-technology sequence, in which students are given information about basic material properties and conventional approaches. Students are exposed to canonical precedents but are not often taught the significance of the particular material achievements of those examples. Learning the foundations is necessary to articulate a more sophisticated vocabulary; however, the rote following of traditional practices practically ensures an unremarkable result. Architectural practice is worse: in the majority of offices, there is no established discipline or method for material innovationdespite the widespread belief in its importance. Moreover, material methods are often discussed purely within a technological context, although the implications of material decisions also affect a broad set of conceptual, theoretical, and design conditions.