1. The Sebaceous Gland Through the Centuries: A Difficult Path to Independence

1.1 The Discovery of the Cutaneous Glands

From the Classical Age to date, a lot of progress has been made in Medicine, but skin diseases only reached their autonomy during the eighteenth century. Before this period, cutaneous disorders were only considered as materia peccans , that means a sign of an internal disequilibrium of humors, which need to be evacuated. Cutaneous pores were seen just as the way by which the body could purify itself.

As a matter of fact, the existence of cutaneous orifices has been observed since ancient times. In the early medical literature, they are usually called pores. It was also known that the skin had some production of water (sweat) and fat (sebum), but the concept of specific glands was not clear until seventeenth century.

Indeed, the fine anatomy of the skin was not the interest of the early dermatologists as it can be observed in the first books devoted to skin diseases, such as those written by Gerolamo Mercuriale (15301606), who wrote the first dermatological book ever [

To be honest, the discovery of the anatomy and physiology of the skin was the result of the efforts of many anatomists especially from Italian and Dutch school. A powerful input came from the invention of the microscope. The first useful microscope was developed in the Netherlands in the early 1600s or even a few years before. Three different eyeglass makers have been given credit for the invention: Hans Lippershey (15701619), Hans Janssen, and his son, Zacharias (15851632). The coining of the name microscope has been credited to Johann Faber (15741629), who gave that name to Galileo Galileis (15641642) instrument in 1625. At this time the magnification was only X3 to X9.

From this period on, the technical improvement of the microscope allowed a more refined anatomy (Fig. ) who, at that time, was professor of Medicine and Botanics at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands.

Fig. 1.1

An old illustration showing one of the first uses of the microscope on the human skin (from: Opuscula omnia actis omnium eruditorum Lipsiensibus inserta, Venetiis, 1740)

Fig. 1.2

A classical image of Malpighi in an old print. The text says: Marcellus Malpighius Medicus Bonononesis Mortuus 29 Novemb. Anno Dom. 1694

Fig. 1.3

Giovanni Battista Morgagni represented when he was teaching in Padua. The text says: Joannes Baptista Morgagnus natuis Forolivii die 25 Februarii anno 1682 in Patavino gymnasio e primaria sede Anatomen ad huc docebat anno 1769

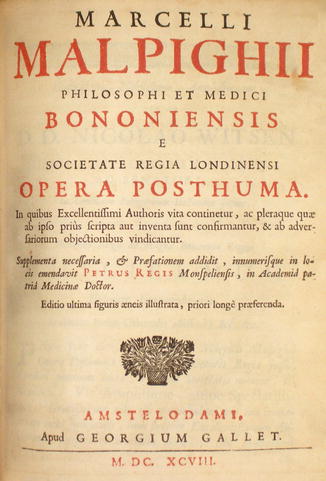

Fig. 1.4

The first page of Malpighis Opera Postuma published in Amsterdam in 1698

Fig. 1.5

An image of Hermann Boerhaave, professor of Medicine and Botanics at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands and partisan of Malpighis ideas

In a letter written to the great anatomist Friederick Ruysch (16381731) (Fig. ) who sent to him an anatomical specimen prepared from a childs cadaver, Boerhaave stated that: after a long and careful observation, with the help of a powerful microscope, I am of the idea that those papules are indeed the follicles of the most simple skin glands. In Boerhaaves opinion, the skin glands are small bags ( utriculi ) and not clusters of small vessels as Ruysch thought after his experiments with the injections of vessels with colored wax. Boerhaave continues his letter stating that Malpighis opinion was the correct one when he stated that these glands are everywhere even though they are very small.

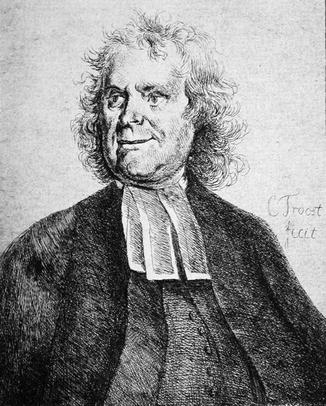

Fig. 1.6

The great anatomist Friederick Ruysch was contempory with Boerhaave but he did not agree with Malpighis observations

In the following lines, he continues the description found in the Opera postuma of Malpighi, in which the anatomist describes both the simple and composed (conglobate) glands. But, to help you to imagine with a better clarity, let me present to you this figure that is described in Malpighis Opera Postuma. In this (Figure 1.1-ure) a,a,a,a indicate the follicles of the simplest glands; b,b,b,b the single emissary vessels, coming from each gland (otricina); these (vessels) take in the common excretory canal; d,c their humors that finally are expelled through the opening c of the canal (Fig. ).

Fig. 1.7

This drawing comes from Opera postuma of Malpighi, in which the anatomist describes both the simple and composed glands

In opposition with this view, Ruysch answered to his friend and colleague Boerhaave, the 1st of June, 1722 stating that: I had to fight, alone, against two great men: Malpighi and you, who both have a deepest knowledge of the anatomy (fabrica) of the human body and who have almost conspired against me. You, has indeed defended the opinion (causa) of Malpighi as it was yours. However I am not sorry, becausereading your writing I have learned something; of this I thank you .

While Govard Bidloo (16491713) [).

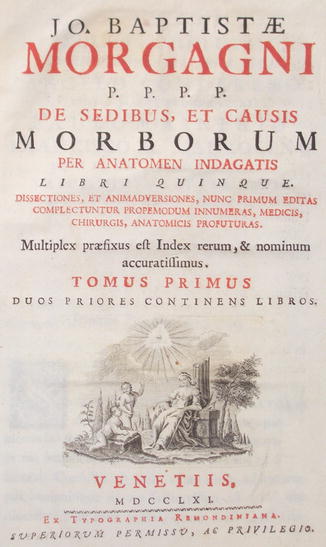

Fig. 1.8

The first page of the most famous book of Morgagni: De sedibus et causi morborum per anatomen indagatis

Fig. 1.9

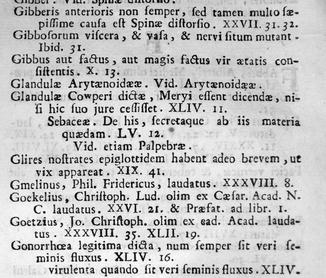

In the index of the same book, immediately below Glandul Cowperi you can read Glandulae sebace

But the opinion of those authors was not accepted by other experts; some, as Ruysch [].