GALATEO

or,

THE RULES OF

Polite Behavior

GIOVANNI DELLA CASA

Edited and Translated by M. F. Rusnak

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

GIOVANNI DELLA CASA (150356) was a celebrated Italian writer and diplomat whose works in Latin and Italian spread across a stunning range of poetic prose and genres.

M. F. RUSNAK is a translator, professor, and writer. He lives in Princeton, New Jersey, and Florence, Italy.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2013 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2013.

Printed in the United States of America

22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-01097-7 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-01102-8 (e-book)

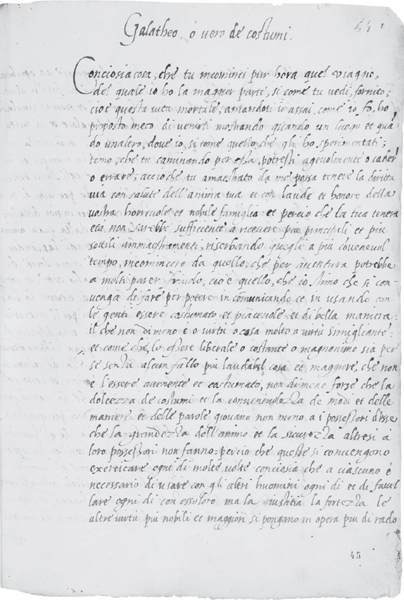

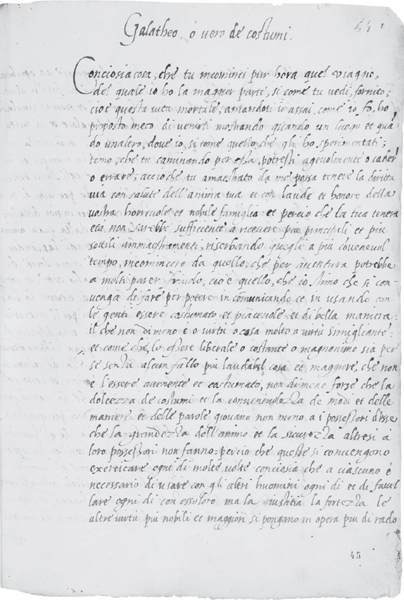

: First page of Galateo (Vat. Lat. 14825, c. 45r.). The original, unexpurgated version is at present the only contemporary manuscript version. Photograph Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Della Casa, Giovanni, 15031556. Galateo, or, The rules of polite behavior / Giovanni Della Casa; edited and translated by M. F. Rusnak.

pages. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-226-01097-7 (cloth : alk paper)ISBN 978-0-226-01102-8 (e-book)

1. Etiquette, MedievalEarly works to 1800. 2. ConversationEarly works to 1800. I. Rusnak, M. F. II. Title. III. Title: Rules of polite behavior.

BJ1921.D4413 2013

395dc23 2013005588

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Contents

.

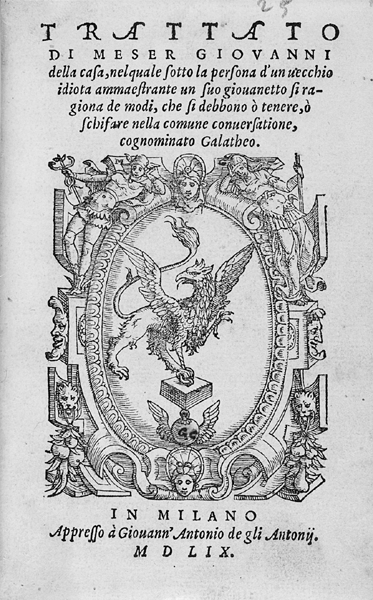

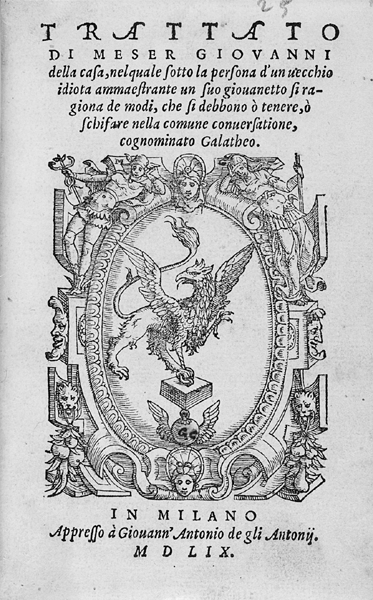

Title page from the Milanese edition of Galateo (1559), the first separate publication. Photograph courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Introduction

In Della nobilt di dame (Venice, 1600), dancing master Fabritio Caroso tells us that women, when walking, should take great care never to give the impression that their feet are more than three fingers off the ground. By placing the foot firmly and straightening the knee attentively, the lady would be able to move ahead with all grace, decorum, and beauty.

Taking the form of a brief and readable guide to everyday courtesy, what we should do and, even more important, what we should not do, Galateo has much in common with two better-known manuals of the Italian Renaissance: Castigliones Book of the Courtier (1528) and Machiavellis The Prince (1532). Galateo is to etiquette what The Prince is to politics, a discourse on action in real life based on the study of the classics and close observation of a complex world. Unlike Castiglione, who wrote from within the Ducal Palace of Urbino, Della Casa does not address the sprezzatura (nonchalance) of idealized courtiers in fancy black dress. Instead, his recommendations are directed toward anyone who has a social life.

On the most basic level, then, Galateo is a collection of precepts on how we should behave in public places, where we are on public view. Although the author was the archbishop of Benevento, he is not interested in the bigger questions of virtue and vice. Instead, he turns his close attention to what that master of propriety Samuel Johnson called the minuter decencies and inferior duties. By dramatizing the trivial behavior of his contemporaries, Della Casa sought to regulate the practice of daily conversation, to correct those depravities which are rather ridiculous than criminal, and remove those grievances which, if they produce no lasting calamities, impress hourly vexation. Della Casa, writing at the end of a long career in the public eye, wanted to get down in writing what it means to be civilized.

What makes Della Casas approach so arresting is the intensity with which he examines our smallest gestures and daily acts. As he writes, And dont be looking like you consider the things discussed above trivial and of small moment, for even light blows, if they are many, can kill ().

WHO WAS GALATEO?

Giovanni Della Casa (150356) was born to a wealthy family from the area above Florence called Mugello, the same countryside where Lorenzo de Medici went hunting and stayed at the Villa Cafaggiolo. Although Della Casa always regarded himself as Florentine, his life was spent mostly outside of Florence. As he notes in the opening lines of Galateo, he was constantly on the move throughout Italy: Bologna, Padua, Rome, Venice, and Treviso.

His early education, which began in Rome where his father was staying on business, was exceptional and based on Latin and Greek classics. The first of his several tutors was Ubaldino Bandinelli, a distinguished humanist whom he recalls in Galateo. He moved to Bologna to study jurisprudence but was drawn away, much as Petrarch was, by the lure of manuscripts and ancient literature. In his early twenties, Della Casa spent a year studying at his family home with Ludovico Beccadelli, another outstanding scholar of Aristotle and Cicero. He then transferred to Padua, where he befriended the accomplished linguist Pietro Bembo, some thirty years his senior and one of the most powerful intellects of the time. As Della Casas brief biography of Bembo (with its touches of autobiography) makes clear, nothing had greater literary prestige at the time than mastering Greek, Latin, and Tuscan. It was in Florence, Della Casa writes, that Bembos tender ears and spirit drank of that pure and sweet Tuscan language. Bembos early writings in Latin and in Italian were remarkable: there was nothing... more refined, more elegant, or more soave to hear.

By the early 1530s, Della Casa had decided to pursue an ecclesiastic career at the Vatican, and he was nominated archbishop of Benevento in 1544. He was following a prestigious career path, suitable for someone with his literary and linguistic gifts, and his writing (mostly in Latin) during this time took the form of orations and letters, often involving quite delicate international affairs. Only in the last five years of his life did Della Casa return to writing poetry and literary prose, secluded in the rural outskirts of Treviso, retired and apparently detached from church affairs. In search of oblio (a scholarly retreat from worldly concerns), he went to the abbey at Nervesa near Treviso, which was bombed in World War I to become the suggestive ruin it is today. Galateo was first published in 1558, two years after he died.

The ancestral Della Casa family villa in Borgo San Lorenzo, Tuscany. Photograph by Adriano Gasparrini.

The title is simply the first name in Latin of another friend and teacher: Galeazzo Florimonte (14781567). Florimonte was the bishop of Sessa Aurunca (near Naples); he was famous in Italy at the time and the author of a commentary on Aristotles Ethics. Florimonte encouraged Della Casa to write an etiquette book, having himself attempted something similar. From all accounts, Florimonte appears to have been a model of refined behavior, self-control, and literary erudition. One of four judges on the Council of Trent, Florimonte was, according to the editor of the first edition of Galateo, admired for his doctrine, and for his manners, and for the goodness and sincerity of his nature, and for true Christian piety and the highest religious faith.

Next page