Kissing Architecture

POINT

SERIES EDITOR Sarah Whiting

Kissing

Architecture

Sylvia Lavin

Princeton University Press Princeton & Oxford

Copyright 2011 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lavin, Sylvia.

Kissing architecture / Sylvia Lavin.

p. cm. (Point: essays on architecture)

ISBN 978-0-691-14923-3 (alk. paper)

1. Art and architectureHistory21st century. I. Title.

N72.A75L38 2011

724.7dc22

2010028286

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Helvetica and Scala

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in China

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Greg

Contents

An art professor once told me that in composition, elements should either overlap or there should be some space between them; that it produces discomfort when things were tangential. He called this phenomenon kissing....

John Baldessari, Kissing Series: Simone Palm Trees (Near), 1975. two color photographs on board, 10 8 in. (25.4 20.3 cm.) each

The First Kiss

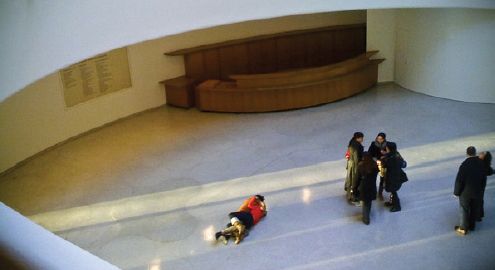

The basic concept was not to try to destroy or be provocative to the architecture, but to melt in. As if I would kiss Taniguchi. Mmmmm, (said with closed eyes and elaborate flourish, a bright yellow down vest, and a heavy Swiss accent). ). The installation also included pink curtains and a gigantic, soft gray, doughnut-shaped pouf, black in the center so it would look like a pupil from above, where scores of people jostled for comfy spots, blanketed by the oozing, pinkish soundtrack playing animato.

1. Pipilotti Rist, Pour Your Body Out (7354 Cubic Meters), 2008. Multichannel audio video installation. The Museum of Modern Art, New York

).

She was speaking with the voice of a non-architect about how a new medium (I call it superarchitecture) and a new sensibilitypostfeminist certainly, but more acutely one of intense affectcould simply and with devastating generosity slip itself on and over the old medium of architecture and its even older sensibilities of authority and autonomous intellection, thereby enveloping the increasingly archaic figure of the architect in an entirely new cultural project. Her remarks offer a starting point for reconsidering disciplinarity, expertise, and medium specificity in architecture today, because her affective yet alien embrace marks a regime change that is happening with neither the confrontation or violence prescribed by the avant-garde nor the endless accommodations of new practice, but through the gesture of a sweetly gentle and yet thoroughly overpowering kiss.

A kiss has been many things in many places (). In the seventeenth century, Martin von Kempe wrote more than a thousand pages on kissing. But even von Kempe could never have imagined that kissing would serve as a theory of architecture. The kiss offers to architecture, a field that in its traditional forms has been committed to permanence and mastery, not merely the obvious allure of sensuality but also a set of qualities that architecture has long resisted: ephemerality and consilience. However long or short, however socially constrained or erotically desiring, a kiss is the coming together of two similar but not identical surfaces, surfaces that soften, flex, and deform when in contact, a performance of temporary singularities, a union of bedazzling convergence and identification during which separation is inconceivable yet inevitable. Kissing confounds the division between two bodies, temporarily creating new definitions of threshold that operate through suction and slippage rather than delimitation and boundary. A kiss puts form into slow and stretchy motion, loosening forms fixity and relaxing its gestalt unities. Kissing performs topological inversions, renders geometry fluid, relies on the atectonic structural prowess of the tongue, and updates the metric of time. Kissing is a lovely way to describe a contemporary architectural performance.

2. Pipilotti Rist, Pour Your Body Out (7354 Cubic Meters), 2008. Multichannel audio video installation. The Museum of Modern Art, New York

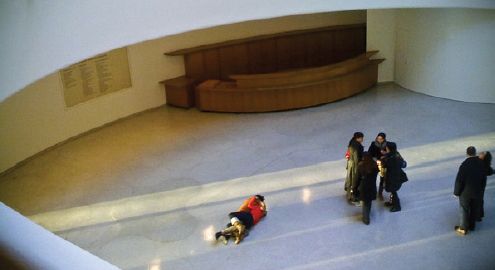

3. Tino Sehgal, The Kiss, performed in 2009. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Kissing is also a gentle way to say goodbye to an old architectural drama in which architecture is inevitably cast as a tragic figure, sometimes victim sometimes villain but always closer to failure than to success. While architectures sense of disciplinary inferiority ultimately derives from the antique pyramid of expression that placed language and poetry at its lofty apex and building down amid the mud and toil of the ground, architectures Sisyphean effort to achieve elevation only became more futile with the development of modern capitalism on the one hand (to which architecture is inevitably attached) and avant-garde strategies of opposition on the other (to which architecture is attached not inevitably but by desire). Architectures original sin was that it could not tell stories in the manner of poetry and painting, although it has certainly tried, offering up such gestures of atonement as architecture parlante and postmodernism. Abstraction solved that problem, because by at least the nineteenth century, painting and all the typically figurative and narrative forms, from graphic design to the novel, were no longer interested in telling stories, and therefore the promise of parity between architecture and the other arts seemed almost in reach. But the very abstraction that made it possible for painting to define itself no longer in terms of the literal content of its images also made it possible for capital to seemingly float free from the literal labor of its productioncapital that most obviously, more obviously than in painting, was needed by architects to build. Different mediums understood and exploited the apparent freedom of this world (which Marxism called the superstructure) in different ways, but for architecture this fantasy freedom became just another source of envy and a new form of cultural privilegethe glorious stance of the rejecting, angry avant-gardist in need of nothing but a paintbrushto which it did not have access. Consider this irony: abstract expressionism is historically coincident with the invention of corporate architecture.

One important strain in contemporary architectural discourse is defined by the net result of these convergent histories of capital and culture. Today the discipline is crippled by a futile debate between those who hold that architecture has failed to establish autonomy and those who contend that architecture has failed to develop adequate means of engagement. During the past thirty years, some have even argued that architectures most important social role is to reveal and repeat this symptomatic hopelessness. As a result, the field has generated a plethora of responses to this double bind, referred to variously as postmodernism, deconstruction, or the neo-avant-garde, that have in common the pursuit of devices for admitting, articulating, describing, mapping, and representing architectures cultural paralysis. Today, I would say at last, this disciplinary Tourettes syndrome, where suddenly and even in the face of tremendous productivity architecture still blurts out a sense of shame, is starting to be understood as self-imposed and more likely to prolong paralysis than move the discipline further. It is precisely release from architectures suspended state of repeated mea culpas that kissing offers.

Next page