For Helena

Contents

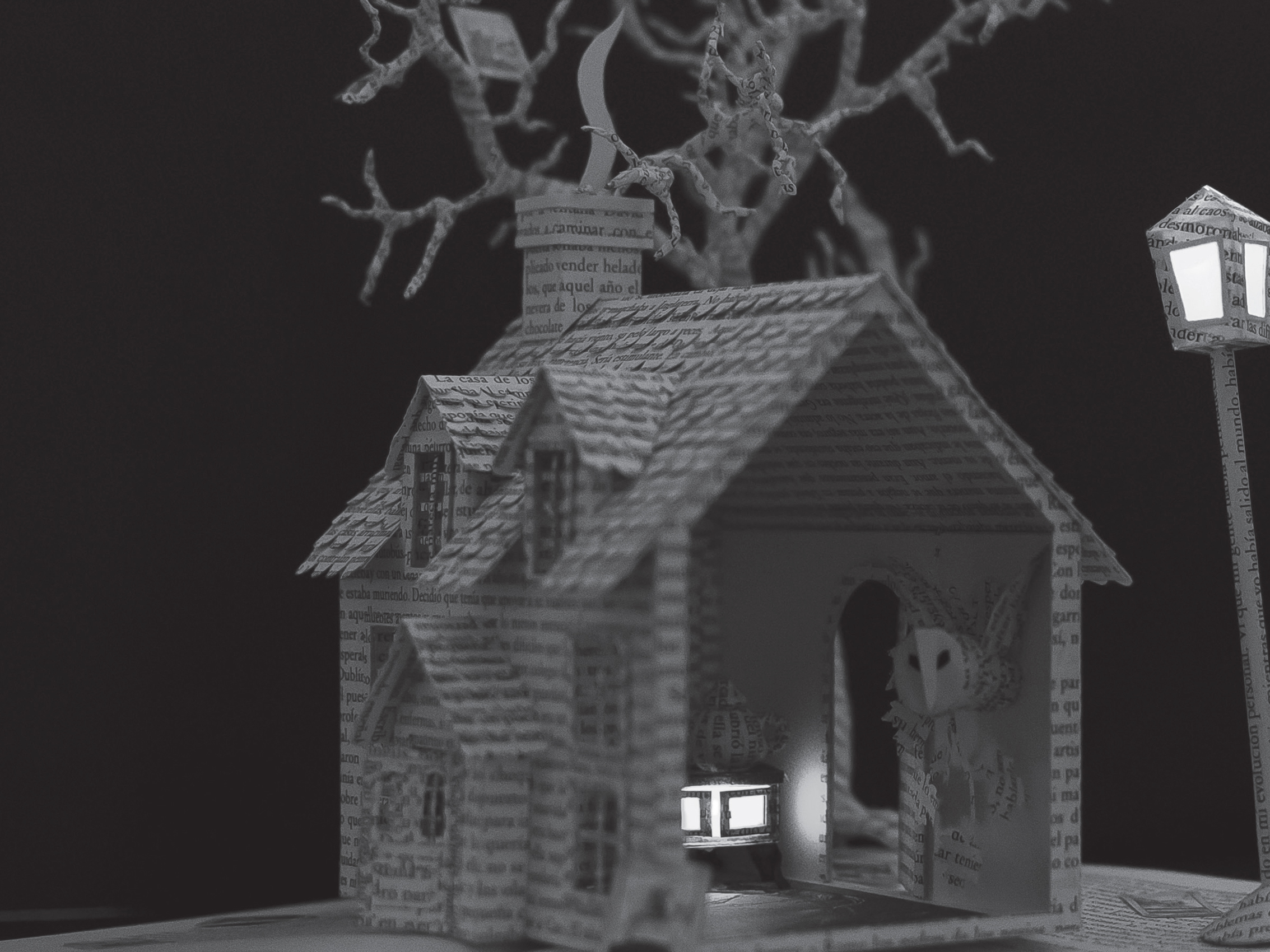

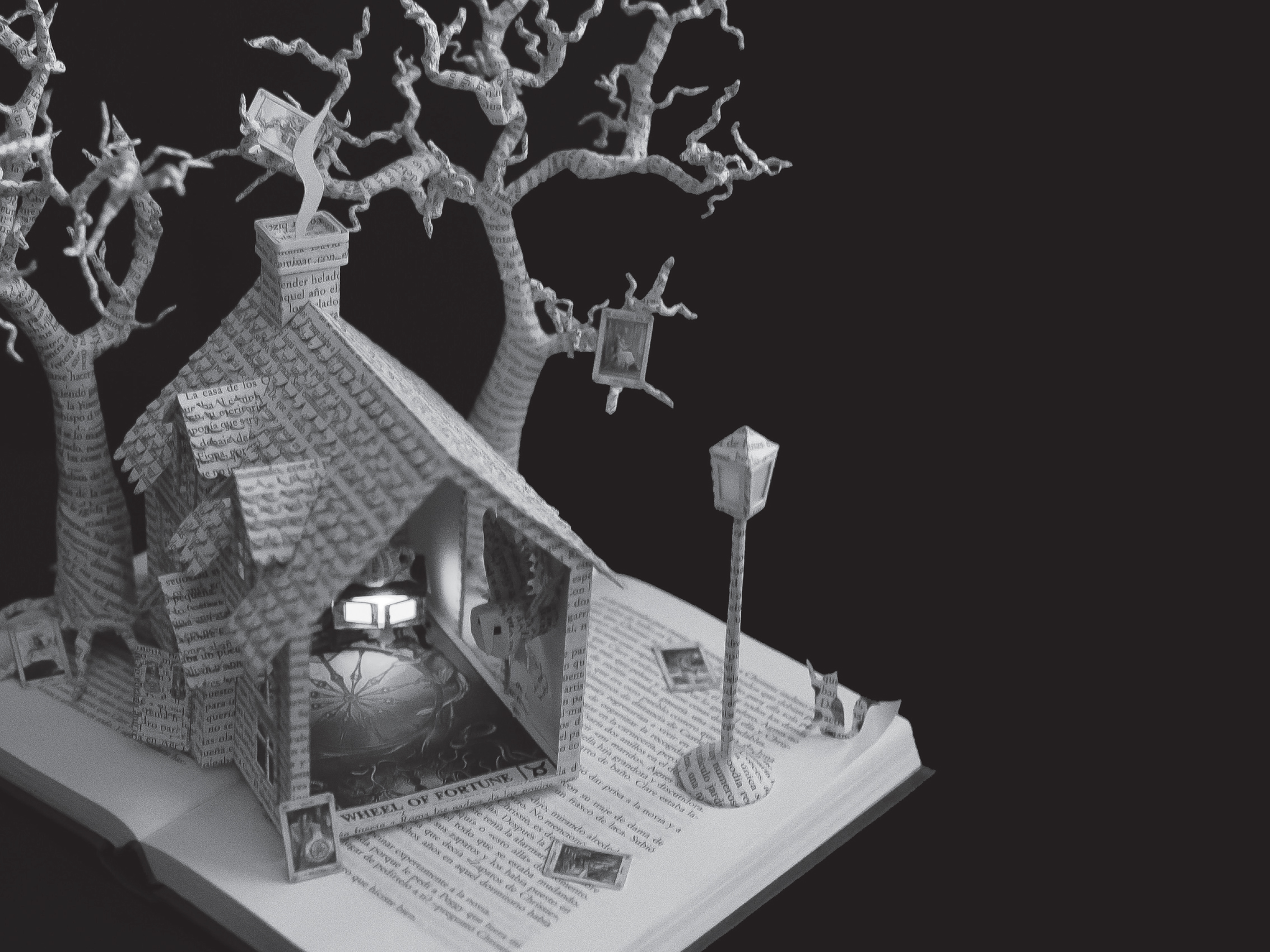

N obody knew what made the three of them from Iona Crescent up and walk out of the world. The rumors were different, depending on who you spoke to. Accident, attacknobody could say for sure, except for Mae Frost and her brother, Rossa. They were there when it all happened, but they were sworn to silence in the way so many survivors of horror are: their tongues held by something beyond their control. Mae wasnt sure shed ever be able to say any of it out loud, even if she was asked. That second summer, away up in the hinterlands where the suburbs kissed the mountains, had stolen the words from her. The language that matched her confession was lost.

Afterwards, when dear old Rita Frost and her ward, Bevan Mulholland, were gone, the national media descended on the twins. Microphones and cameras desperate to harvest their sorrow and turn it into headline ink. Lucky was what those headlines had called Mae and Rossa. Lucky, like spotting a bright penny on a pavement, lucky like two magpies seen together for joy. Lucky, like the twins escape had happened by chance.

Not a trace of Bevan or Rita was found. The twins were discovered by police and the fire brigade, sitting on the roadside at the end of Iona Crescent, holding each other. Streaked with soot, hands bloodied, but otherwise unharmed. Seventeen, the pair of them, wide-eyed and gaunt for months. Theyd never be the same again, said the papers. It was a miracle, whispered the neighbors. Those lucky, lucky kids.

All they told the journalists was that they ran for their lives. They would cast each other looks, Rossa and Mae, as they said just about nothing at all under rapid-fire questioning. Shock was the disguise they wore, and it protected them from having to say much at all.

The only detail real Mae ever gave to the tall, coal-suited reporters as they grilled her was that she hoped Bobby the cat had managed to make it out into the mountains. They always liked that bit. Their eyes would come over sad; they would say she was so brave.

The neighbors on Iona had been far more forthcoming. Devastated, all: Rita Frost was such a sweet old lady. And young Bevan, tabloids were splashed with photographs of her, school headshots, the occasional clumsy selfie. A gorgeous, bright girl struck down before her life had really begun. Her former boyfriend, Gus, gave an impassioned missive to the national broadsheet about the strength of her character, her beauty. There never would be anyone quite like Bevan Mulholland again, hed said.

Mae had agreed with him, when shed read it. There wouldnt be anyone like her again.

While the papers flooded with tributes, it seemed to Mae that nobody remembered that Bevan and Rita had kept themselves to themselves. That Bevan had few friends, if anythat she was a quiet girl with something hard in her eyes. That Rita had been little short of shunned by the parish for operating as a psychic medium from her living room.

No use in remembering the harder things, the stranger things. Rita was kind and Bevan was beautiful, and Audreywell, what would anybody at all really know about Audrey? Audrey had been gone for years.

Rita was kind. Bevan was beautifulthis is what remained. This, and the smell. They talked about it for years, told stories of how the sky above Dorasbeg had looked tornado-gray; a disaster in the air. Great billows of it carried on the wind down over the village and the motorway: smoke, sweet and dark.

T he floor is tiles and sawdust, like dry, flaked snow. You shuffle your feet and make little heaps of the fine wood shavings, here and there. Your fruit gum tastes like nothing. Youre last in the line. When the gray-faced old man and the woman with the pram are gone, itll be just you and the butchers son, Gus.

You havent looked at him just yet; instead you inspect each cut of meat behind the glass counter. Thats what you must look like on the inside, you think, running your gaze over the crimson flanks, the pastel translucency of breasts, the redness of mince.

Gray old man leaves, paper bag under his arm. The bell on the door rings as he opens it, closes it. For a moment, the cool of the shop is disturbed by the hot summer air outside. The woman with the pram moves forward, leans over the counter, goes, Will you do us up a chicken with stuffing and a spice rub? Cheers, now, Gus.

Boring. You drag your fingertips over the glass, tap your nails against it. You blow a small bubble with your gum, it snaps. An impatient sound. Gus looks over at you, takes you in. Ill be with you in a moment, Bevan.

You hum back to him. Whatever.

He tuts like hes exasperated, but you know he likes you. Thats funny.

Gus snows the pimpled chicken skin with salt, pepper, something red from a canister. Stuffs it with bread crumbs and sage and onion and butter. Puts it in a little tin dish, wraps it in cling. Keeps flinging you looks while he works. The woman with the pram passes a fiver over the counter. His latex gloves are still covered in the rawness of the bird as he takes the green note. You lean back against the arc of the counter, the skin on your legs sticking to the glass. Chilly.

Whatll it be, Bev?

Guss voice is flat, like hes not interested in helping yourather, like hes playing at not being interested in helping you.

Bones again, if you have them.

You slide your eyes up him, his bloodied apron, his denim shirt. This is his das shop. Hes still in school, only working for the summer. Hes got a pair of cheekbones you could sharpen a knife off. Starving green eyes. Cornfield-fair beard and woolen hat over tufts of straw hair. Safety hazard, that. His ma told Rita that hes got notions of moving to London after school, getting out of the family trade, starting over. Wants to do tattoos for a living. You can see a couple of inky surprises peeking from under his cuffs.

More bones? He is incredulous. Using them to pick your teeth?

Soup. You flip out your phone, thumbing open the lock screen, posing indifference. For Rita.

Give it over. Youre smudging the counter, he snaps, hands on his hips.

Make me, you reply, popping another small bubble.

What kind of bones?

Whatever youve got. You dont take your eyes off your digital feed, but you arent reading it, not really. He loves it, your indifference getting right under his skin.

He hisses and disappears behind thick plastic curtains to get you what youre looking for. Good boy.

You start to sing along with the radio while hes in there, loud enough given theres nobody else around. It feels like the stations have only been playing four songs this summer, all of them bangers. You sway side to side along with the chorus, raise your arms above your head, kick the sawdust. Beats easy, words dark. Pay me what you owe meyou sort of lose yourself in it, synth overtaking your limbs a little. Its cold in here to keep the meat fresh. The hairs on your arms rise.

Gus comes back, holding a blue plastic bag weighed down with bones. Theyll be wrapped in cling, then yesterdays paper. You smile at him, still dancing. Take a break? This is such