This book is intended for film professionals, educators, and students alike. While it is not meant to be a how to guide for the DIY filmmaker, it documents the best industry practices currently in place, the very latest technologies, and sheds light on emerging trends in digital filmmaking. Our goal is to demystify many of the underlying concepts and philosophies behind those topics so that the reader can apply them to future innovations, as the industry is in a constant state of flux and technologies change daily.

What has been standard operating procedure in the past may not be the best way to do things in the current environment. While we have made every effort to stay up to date, more than likely some of the technologies referenced here will have become obsolete upon publication. To that end we do not endorse any particular manufacturer or vendor, and hope to keep the conversation focused on overarching workflows rather than specific products. More often than not a producer, director or even a working film editor may have questions that need answering. This book is the first desk reference that they should reach for. Our goal is to discuss current technologies and practices, but, more importantly, provide context and insight into the concepts behind them, their place in the industry, and how to adapt as filmmaking inevitably evolves. Within academia, the benefit offered here is an encapsulated history of the filmmaking process as well as an overview of digital filmmaking work-flows, allowing todays students to tell their stories more effectively.

Chapter 4.4

Dirt Fixes, Adding or Removing Grain and Noise

It is ironic that many modern digital productions have employed methods in post to artificially add hair and scratches, film weave, tears, burns and blemishes to suggest an aged, analog film experience that suggests a now-historical authenticity. Even today, non-digital film elements continue to go through lengthy, painstaking restoration processes specifically to remove these unwanted elements and leave behind a pristine master that can be archived for the future. While there are automated systems used to analyze and correct these issues, the final arbiter must be a set of human eyes. Computer programs may offer a cost-effective solution to the problem but they risk compromising the quality of the final product by softening the image or introducing unwanted artifacts.

It is an unfortunate reality of working with tangible film stock that they attract a fair amount of dust over time. The preferred method for physically removing this dust is sonic cleaning, which uses a combination of a fluid solvent and sound waves to literally shake the dust particles off. However, this method will not remove 100 percent of the offending dust, grease or dirt particles and they will be visible once the reel is digitally scanned. Dust on the negative appears as a bright dot that may be a few pixels wide. Systems such as Autodesk Lustre can automatically identify digitally scanned frames for dirt and eliminate them by interpolating pixels much like Photoshops Healing Brush. Many post houses will employ a dirt removal system (DRS) prior to final color correction so that the eventual master of the film is as pristine as possible. Another method is to hand the reel over to a specialist who visually checks it during playback for dust. In this case, a manual or semi-automated system is used in order to replace the area in question with pixels from a frame immediately before or after the event. Alternately, adjacent pixels are cloned to cover up and paint over the blemish.

Damage removal may require further analysis of each problem area to come up with a creative solution. While not always 100 percent successful for restoration, damage removal can take the curse off (i.e., make problems less noticeable).

Common types of film damage:

- Scratches, tears, and hair

- Film weave

- Discoloration and fading

Film weave can originate in camera, in printing, in optical VFX, and in scanning. Image stabilization techniques can sometimes fix these issues. However, most stabilization algorithms will subtly zoom in the image with a resulting trade-off of subtle reframing and softening. Discoloration and fading can be addressed in the color correction sessions. All of these issues require additional process and rendering time.

Film labs used to offer a technique known as wet-gate printing to remove surface scratches from original negative. This involves adding a liquid layer to the film surface which effectively fills in the scratches to make them less visible. Today there is a similar technique known as wet-gate scanning which combines the liquid process with an algorithm that measures adjacent pixels and replaces them where scratching occurs. While this cant entirely remove dirt or fix deep scratches, it would be the first step in restoring damaged negative.

Ultrasonic cleaning system

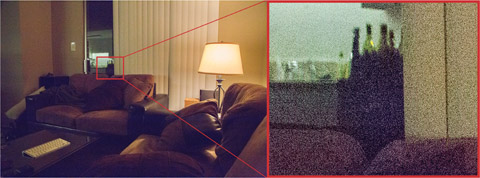

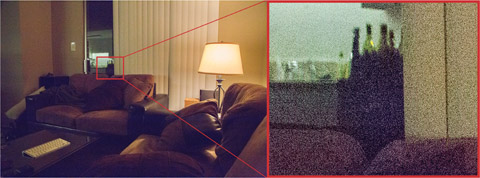

Grain can be defined as the clumping of silver halide crystals in the film, which adds texture to the image. Depending on the type of project, this may be desirable to the filmmaker or an unwanted side effect. For years audiences became so used to seeing grain in film that no one really noticed until it was absent from the digital image. Filmmakers sometimes add grain back in for creative effect to provide lyrical expression or for the recreation of historical imagery.

Just as no two shots entirely match in terms of color, consistency of grain between shots has become an issue. We see frames today with such clarity and precision that the presence of grain (or lack thereof) has become more noticeable to the casual viewer. Grain patterns are more visible when shots are blown up, different film stocks are used or when the film has been pushed (overexposed) in the camera. Nebraska (2013) shot on the Alexa and added film grain and the black-and-white look in post.

As existing film libraries are re-mastered for the digital realm, content owners must contend with the issue of grain and make a decision whether to remove it or leave it as is. Purists may elect to keep the original grain whereas some distributors prefer that it be gone. Choosing either path has certain trade-offs. Preserving grain in the digital copy means risking artifacts. Depending on the level of compression, some grain clumps may appear as square blocks. Blu-Ray authors sometimes need to leave room on the disc for promo and other bonus materials, thus requiring the main feature to be compressed at a lower bitrate. If increasing the encoding bitrate is not possible, there are video noise reduction ( DNR ) systems available at most post houses. While these systems are highly automated resulting in cost savings, they produce an unfortunate byproduct in that they tend to soften the image, resulting in faces that look waxy and unnatural.

Digital noise is loosely analogous to film grain

Grain or No Grain?

When studios first began to re-master their back catalogs for high definition (HD), the general consensus was to scrub every frame clean. However, cinephiles balked at this notion and in time the studios backed away from sanitizing their old movies. There are very powerful tools that can minimize grain or add it back in depending on the needs of the client. Grain management in updating films is now part of a larger discussion, as restoration expert, Tom Burton, explains: