T HE J OHNS H OPKINS U NIVERSITY P RESS

D IRECTORS C IRCLE B OOK FOR 2011

The Johns Hopkins University Press gratefully acknowledges members of the 2011 Directors Circle for supporting the publication of works such as Hart Cranes Poetry.

Anonymous

Alfred and Muriel Berkeley

John and Bonnie Boland

Darlene Bookoff

Jack Goellner and Barbara Lamb Charles and Elizabeth Hughes John T. Irwin

John and Kathleen Keane

Mary L. Kelly

X. J. and Dorothy Kennedy

Eric R. Papenfuse and Catherine A. Lawrence

Jane Wilson McWilliams

Anders Richter

Guenter B. Risse

R. Champlin and Debbie Sheridan

Winston and Marilyn Tabb

Daun and Patricia Van Ee

John T. Irwin

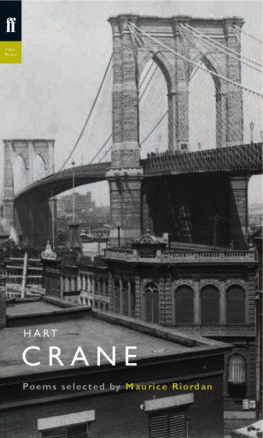

Hart Cranes Poetry

Appollinaire lived in Paris, I live in Cleveland, Ohio

The Johns Hopkins University Press

Baltimore

2011 The Johns Hopkins University Press

All rights reserved. Published 2011

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The Johns Hopkins University Press

2715 North Charles Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363

www.press.jhu.edu

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Word & Image, Raritan Review, and the Regents of The University of Arizona for permission to use revised versions of the following previously published material: Foreshadowing and Foreshortening: The Prophetic Vision of Origins in Hart Cranes The Bridge, Word & Image 1(JulySeptember 1985): 288312; Hart Cranes The Bridge, I, Raritan Review 8(Spring 1989): 7088; Hart Cranes The Bridge, II, Raritan Review 9(Summer 1989): 99113; and The Triple Archetype: The Presence of Faust in The Bridge, Arizona Quarterly 50(Spring 1994): 5173. Back Home Again in Indiana: Hart Cranes The Bridge was originally published in the Raritan Review and then reprinted in Romantic Revolutions: Criticism and Theory, edited by Kenneth Johnston and Herbert Marks (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990), 26996.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Irwin, John T.

Hart Cranes poetry : Appollinaire lived in Paris, I live in Cleveland, Ohio / John T. Irwin. p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN -13: 978-1-4214-0221-5 (hardcover : acid-free paper)

ISBN -10: 1-4214-0221-1 (hardcover : acid-free paper)

1. Crane, Hart, 18991932Criticism and interpretation. I. Title.

PS 3505. R 272Z725 2011

811.52dc22 2011004060

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book. For more information, please contact Special Sales at 410-516-6936 or specialsales@press.jhu.edu.

The Johns Hopkins University Press uses environmentally friendly book materials, including recycled text paper that is composed of at least 30 percent post-consumer waste, whenever possible.

As always, for Meme, my beloved.

And for the outrageous Harold

Contents

Preface

This is a somewhat old-fashioned kind of book. It is a reading of Hart Cranes poetry that brings to bear on the poetic text information from a variety of sources (e.g., art history, history of ideas, biography, psychoanalysis, classical literature, philosophy, mythology, and so on). What this reading of Cranes work aims to show is that The Bridge is the best twentieth-century long poem in English and that it is the best not by a little but by a lot. Among modern long poems it is the richest and most wide-ranging in its mythic and historical resonances, the most inventive in its combination of structures drawn from literature and the visual arts, and the most subtle and compelling in terms of its psychological underpinnings, to name only three areas in which it excels. This book also argues that the best entry to the shorter poems in Cranes first volume, White Buildings, and to his last poem, The Broken Tower, is through his epichence, the rationale for this books organization. Where previous studies of Cranes poetry have characteristically begun with an examination of his shorter poems and then proceeded to The Bridge, this study reverses the process by beginning with an examination of the long poem and then taking on the poems in White Buildings and The Broken Tower. Any reader of Cranes poetry knows the difficulty involved in interpreting the poems in White Buildings, a difficulty created by the density of their imagery, the brevity of the context any individual poem presents, and the demands made by Cranes logic of metaphor, a poetic practice that depends on the so-called illogical impingement of the connotations of words (Crane 165) on the readers consciousness. But in The Bridge with its implicit narrative thread, a subject matter ostensibly rooted in American myth and history, and an enlarged context to clarify repeated structures, images, and key words (a context that can be invoked to supplement the restricted contexts of his shorter poems)the reader has the best road map for navigating the rest of Cranes poetry. That is why this study deals first with Cranes epic.

Cranes two sometime friends, Allen Tate and Yvor Winters, largely set the tone of the initial critical response to The Bridgea response that saw the poem as a magnificent failure. And later critics often believed this judgments accuracy was in some sense confirmed by Cranes suicide two years after the poems publication. Tate and Winters, both college educated, would go on to distinguished academic careers as poet-critics, while Crane, with only a high school diploma, would educate himself through reading and through conversations with friends (mostly writers and visual artists). But Crane was a major poet, and Tate and Winters were minor poets, and their initial reaction to The Bridgewhile ostensibly arguing that Cranes poem was too Romantic and Whitmanian, too extravagant (and thus foredoomed) in its optimism, not modern and Eliotic enoughmay also have represented a degree of professional ressentiment (to use Nietzsches word). Both Tate and Winters also remembered personal quarrels with Crane, often caused by Harts boisterous or erratic behavior when drinking: such memories may have made the two academic poet-critics feel that the high-school-educated, roaring boy of modern American poetry could not possibly have written an epic. Their reaction may have been further complicated by the fact that though The Bridge, in its effort to be a synthesis of American myth and history, was strategically an epic, it was tactically a lyric, seeking to achieve that strategic epic goal through a disjunctive series of lyric epiphanies in its sections.

This Tate/Winters sense of The Bridge as a magnificent failure was accepted critical wisdom when I first read Crane in college in the early 1960s, though by the time I came to write my dissertation on the poem in graduate school a few years later, the situation had begun to change. The change was driven, it seems to me, by two factors: first, a more sophisticated reading of what Romanticism involved was making readers realize that much of the best twentieth-century English and American poetry was late Romantic; second, a generational change in attitudes in the mid-1960s made that vision of American origins (which Crane had created in The Bridge as a prophetic image of Americas future) seem less a matter of extravagant optimism than one of practical necessity. Cranes vision of the pre-Columbian Indian world (to which he imaginatively journeyed back in the poem through his surrogate, the poetic quester) was one in which a native people, spiritually wed to the physical nature of their land, cultivated and cared for the environment as if it were a beloved parent or a spouse, rather than exploiting it. The prophetic vision of an eventual return to such an origin (which is to say, to the environmental attitudes it entailed) clearly struck a responsive chord with young people in the 1960s. Since then, it seems, the reputation of

Next page